Born in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, in 1973, Lim Kah-Wai graduated from Osaka University, majoring in Electrical Engineering, in 1998. Lim studied film in Beijing Film Academy in China after 6 years of Network Engineer in Tokyo. His directorial debut “After All These Years” was shot in China in 2010. He was a jury member of Winds of Asian section at the Tokyo International Film Festival in 2012. He finished “Fly me to Minami” in 2013 and the movie was selected in Osaka Asian Film Festival. He was also elected as the “Director in Focus” at South Taiwan Film Festival in 2013. His latest Chinese film “Love in Late Autmn” was commercially released, through major a cinema chaina in China and Hong Kong this year. He is now living in Osaka and will prepare for a trilogy about the city Osaka titled “Come and Go”.

You were born in Kuala Lumpur, but you have lived and worked in Japan and China. How did that occur and in what way has it shaped you as a filmmaker?

After high school graduation in Kuala Lumpur, I came to Japan to study electronic engineering. After I graduated from the university, I worked as an engineer in Tokyo for six years. Then I decided I wanted to make films and I went to Beijing Film Academy, to study filmmaking. Since then, I started to live and work among Japan, China and Hong Kong, depending on the film project I was involved with. The fact that I do not have a particular base in any of those countries allows me to retain the point of view of the outsider, as I look inside these societies and the people. I think this point of view has influenced the films I made.

Your films feature actors of different nationalities. Why is that, and is it difficult to direct and coordinate people that speak different languages?

The first film I made when I studied in Beijing Film Academy is a short film. It is about a French guy who gets lost in the maze of Beijing. I made this film with my friends, who were studying or wandering in Beijing during that time (2004), including Italian, American, Canadian, Japanese, Koreans, and Chinese. The main reason might be that I feel more comfortable or easy to communicate, on a project, with people from different countries.

Another, practical, reason is that it was too easy to make friends from different countries in Beijing, at the time. You could stay in China for a long time without a working visa, with very little living costs. Obviously, a lot of foreigners went there to look for opportunities. However, it is getting difficult and strict for foreigners to stay in China now. From the beginning, I got used to work with different nationalities, which are not related to my film or its story. This kind of filmmaking, naturally, influenced the other films I made afterwards.

I do not find any difficulty to coordinate and direct people, and it is not because I can speak English, Chinese, Mandarin and Japanese, but mainly because I never think language is a barrier for us to communicate. As human beings, I think most of us have common emotions and thoughts, no matter our nationalities. Especially in the process of filmmaking, language is never the main problem. Even when you work with a team of people of the same nationality, you will still have many problems of communication to solve

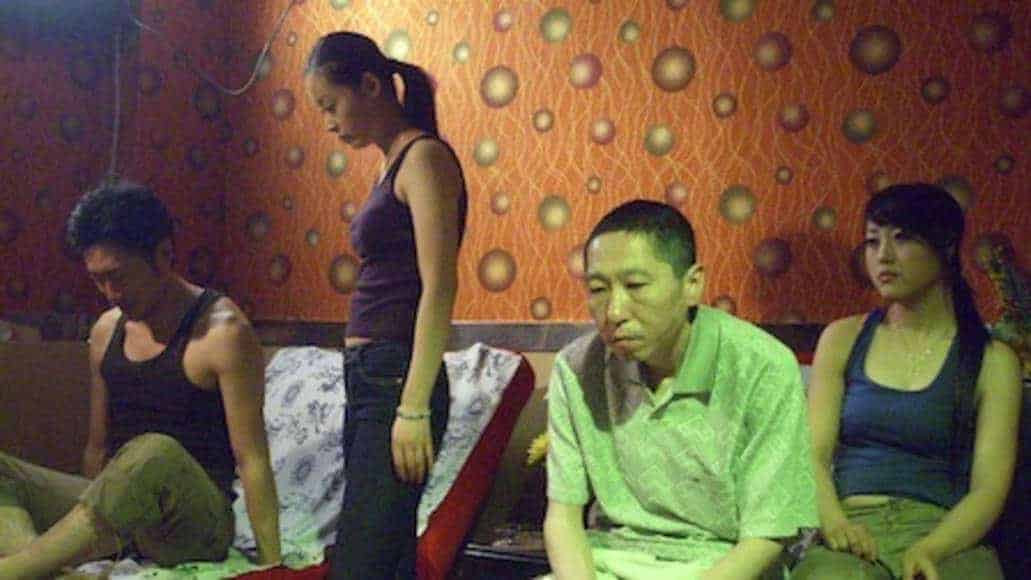

In “After All These Years,” what did you want to show with the protagonist nobody recognizes, both in the first and in the second part, which occurs after some years.

If I had used different actors and actresses to play the same roles in the first and the second part, then the audience would not feel the confusion, they would naturally think that there are 2 stories in 1 film. However, I used the same actors and actresses, and even the same location in 1 film with 2 stories, in order for the audience to feel the confusion and to interpret them as a single story. I find this kind of confusion and interpretation very interesting, especially when I kill one of the protagonists in the first half but bring him alive in the second. I think this kind of confusion and free interpretation happen because audiences, in general, believe what they watch and hear through a film, and never doubt about it. It is like what we believe about identity. For me, however, identity is always doubtful, based on a common fiction or illusion we believe. “After All These Years” is a film about identity and existence, so, if the protagonist has no one recognize him, it will make this concept and my perspective more obvious.

“After All these Years” is a very difficult film to watch, an experimental movie in principle. “Magic & Loss” is definitely art-house, but much easier to watch, and “Fly me To Minami” even more. Why and how did that change occur in your films, since they become more accessible to wider audience as time passes?

“After All These Years” is my first feature film. I think the first film of most filmmakers is very personal. It is always a story about himself or the place, or the history of him/her growing up. At the same time, it is very ambitious, to the point that the filmmaker does not care about the others understanding it, especially when the film is independent, low budget, without the limitations of the market. Therefore, I tried to put all my interests, concepts, ideas and styles I love into this film.

For example, the first half is standard size and black and white, the second half is in color and widescreen, and the structure of the film is very complicated, and I also tried to put the title “After All These Years” in between the first and second half to mislead audience on purpose. In the end, the audience will realize they just experienced a parallel or a fictional world with different layers. I think this style and concept is very original and challenges the way we watch films, usually. “After All These Years” was made in 2009, I think it is much earlier than Wes Anderson, Jia Zhangke and Hou Hsiao Hsen changed the frame size in a film to tell differently structured stories.

Anyway, “After All These Years” seems very difficult to watch, but the story might happen everywhere as it deals with very personal emotion. For example, I always had a fear that no one will recognize me, even my family and friends, when I return to my hometown, after all these years

For me, “After All These Years” and “Magic &Loss” are kind of meta-movies. Particularly in the second one, I tried to make many loops inside the film. There are many entrances and exits inside the film, the viewer will get lost if he does not see the points in and out. At the same time, it could also be interpreted with different point of views, as one could start watching the film from any timeline, just as there the same way there are some poems or novels that can be read from any page. One can even watch the film from the last shot and then begin again from the first.

In terms of structure and style, I tried to make my first and second movie to challenge audience preconceptions on film. However, as you know, this kind of experimental or art house films are not easy to survive in the market, and I also thought I had explored enough about what I want to do in film. Therefore, after these two films, I wanted to access a wider audience, so I shot “New World” and “Fly me to Minami.” Furthermore, my latest production, “Love in late Autumn” is a purely commercial, mainstream film, which was released widely in China and Hong Kong last year.

However, if you look into them carefully, I think my films still have some common style and insistence, especially in terms of the language of cinema, like long takes, very few reverse shots, few close up shots, more tracking shorts etc.

Your films, particularly “Magic & Loss” and “Fly me To Minami,” present many different locations, to the point that they function like tour guides, at times. Why is that?

For me, location and space are always among the main characters in a film. It is difficult for me not to show how the protagonist walks on the street and then comes to an apartment by elevator, ladder etc. Additionally, the doors and the windows of any space are always my big concern. I want the audience to organize the image of the space you show them, little by little through the entire film, and by the end, to reconnect those images unconsciously, and then have a clear picture about the space of the whole film. Therefore, this might be the reason you feel it look like a tour guide, but in fact, I am not making a film for travel purposes, I just want the audience to feel the atmosphere and the space the protagonists are involved in.

In “Fly me To Minami”, all protagonists suffer from a sense of loneliness. Do you believe that this is a common “illness” of the modern man? Moreover, do you think relationships are as difficult as portrayed in the film?

I do believe loneliness is the most common illness of our times. The most obvious example is that, nowadays, we have all become slaves of Facebook, Instragram, Twitter etc. As we rely, more and more, on this kind of SNS media, the fact that we are very lonely and have a big desire to share and to get to know other people becomes growingly evident. I think that any kind of relationship is a process of compromising and giving up your preconceptions. It is not easy to start any kind of relation, but it is even more difficult to maintain it for a long time. There is no right or wrong side; it is just our weakness as human beings.

Cross-cultural issues seem to be one of the main themes of your films. Why do these issues inspire you?

In the beginning, I did not intend to make a film dealing with cross-culture issues, but after shooting “Magic and Loss” in an isolated island in Hong Kong with a Korean and a Japanese actress I started to feel that it might be one of my main themes. Then I shot “New World” in Osaka and Beijing, to explore the economic and political relationships between Japan and China and “Fly me to Minami” to tell two love stories that overcome the restrictions in language and culture between Japan, Hong Kong and Korea. These ideas and stories come very naturally to me when I travel across those countries. However, if you are not Asian, or you do not know these cultures well, you could, probably, not identify the differences among Chinese, Japanese and Korean, and appreciate the cross-culture issue I tried to explore in my films. I hope, after watching my films, audience will be more interested in the differences between those countries. In fact, there is a lot of history and political issues in those countries, and I will try to explore this kind of issue in my future projects.

Generally, what else inspires you to make movies? Which are your influences as a filmmaker, and what kind of films do you like to watch? What are your plans for the future?

Before I decided to study filmmaking in Beijing, I was a cinephile. I watched almost 400 films every year in cinemas in Tokyo, not on DVD or video. Most of them were old films, especially Japanese films before the 80's, American of the 40s and 50s, and European New Wave.

I have many favorite directors, but my all time favorites are Naruse Mikio, Mizoguchi Kenji, Masumura Yasuzo, Howard Hawks, Lubitsch, Fritz Lang, Jacque Rivette and Jean-Luc Godard. I think I watched most of their films in cinema when I worked in Tokyo as an engineer. Definitely, my films are not as brilliant as their masterpieces, but I think their style and ideas on film influenced deeply my own.

After “New World” and “Fly me to Minami,” I would like to make another film in Osaka; it will be the last part of my Osaka trilogy. It will have the same theme as both of these films, to explore the relationship of Japanese society with other countries. However, this time I will try to expand it to more nationalities, not only East Asia (Japan, China, and Korea).

Last year, I backpacked around East Europe for around 5 months, and I found that those areas are very interesting and cinematic, especially Slovenia, Croatia and Montenegro. I am thinking of making a film in those countries in the near future. It might be a story like “Magic & Loss” I made in Hong Kong before. I also have a project to make in my home country, Malaysia. It will take place in the border between Malaysia and Thailand and will tell a story about a secret community, which is forgotten by history. Anyway, I think I will not make films in a specific country in the near future, since I really found out a lot of possibilities and stories in order to make films in different countries.