Films taking place in the 80's and 90's have been one of the recent trends of international cinema (“Stranger Things” has probably something to do with it), with the majority of them trying to benefit from the sense of nostalgia they emit. Isao Yukisada (one of the most talented contemporary Japanese directors in my opinion) makes his effort in the style, through a combination with teen, high school drama based on the homonymous manga by Kyoko Okazaki.

River's Edge is screening at the 17th New York Asian Film Festival

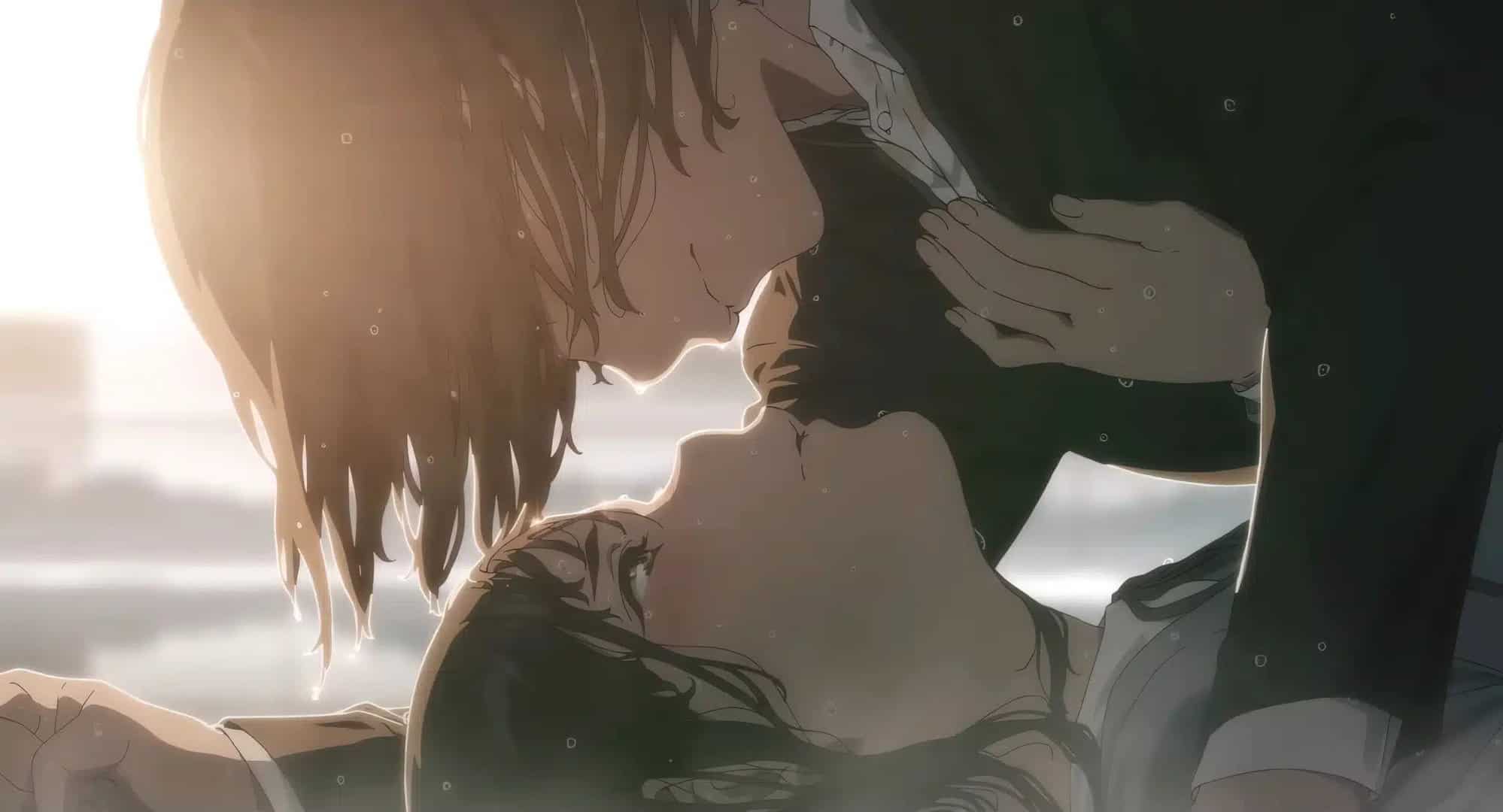

The story takes place in the 90's and revolves around a number of characters who attend the same high school. Haruna is a girl who appears detached from everything, despite the fact that she has a boyfriend, Kannonzaki, and is part of a gang of the three that also includes Rumi, a girl who has sex with mature men who shower her with expensive gifts, and another girl, who is the gossiper of the class. Ichiro is a homosexual boy who is constantly bullied and beaten, particularly from Kannonzaki, who seems to hold a grudge against him. Haruna realizes the fact and she repeatedly tries to save Ichiro, with the two of them forming a peculiar friendship. Ichiro eventually introduces Haruna to his “treasure”, the dead body of a man who has been rotting in the weeds in the edge of the river that passes through the city (thus the title) and the other friend of his, Kozue, a teen model with bulimic tendencies. The three of them also become a gang, with their relationship resulting in a number of shockwaves, particularly regarding Kannonzaki, and Kanna Tajima, a girl who is supposedly Ichiro's girlfriend, although their relationship is extremely one-sided. As angst, truth, and sex take over the various relationships, violence soon ensues.

Yukisada takes the somewhat far-fetched story of the original in order to direct a film that focuses on the kids of the era, and the consequences the lack of guidance from parents and teachers (both of which are almost non-existent in the film) have to youths. This concept is actually depicted in every character. Haruna has adopted a stance of detachment and insensitivity towards almost everything that takes place around her, with her sole care seeming to be Ichiro, although the reasons never become actually clear (perhaps he likes him as a man, although it never becomes clear). The same applies to Ichiro, who has found a rather unusual solace in the weeds (both literally and metaphorically) in order to cope with the constant bullying he has to face. In the same fashion, Kannonzaki has turned to violence in order to cope with his broken family, and Rumi to sex for roughly the same reasons, who include her extremely nosy sister. Kanna has “decided” to turn a blind eye to Ichiro' s indifference in order to convince herself that she has found love (and to brag to her schoolmates who consider him gorgeous) while Kozue's effort to stay thin and beautiful according to the standards of the teen idol concept, has led her to an extreme case of bulimia and a detachment similar to the one of Haruna's.

Through these characters and their behaviour, Yukisada paints a rather bleak picture of the world during the time, with the kids appearing to belong to a lost generation, as they roam the streets aimlessly and without any kind of resolve to pursue goals they do not even know about. Even those who do know their goals though, (Kanna wants to be with Ichiro, Kozue to pursue a career in the show business, Rumi to get expensive stuff) are presented even more disoriented and futile, to the point that their efforts become their destruction.

In that fashion, Yukisada paints a really dark portrait of the era, a world where hope is nowhere to be found and violence and death seem to lurk in every relationship. In this effort, he is benefitted the most by Kenji Maki's cinematography who presents images where grey and dark colors dominate, with the tactic reaching its apogee in the presentation of the reef area, which appears as a dystopian setting, while sharing some (minor similarities) regarding its context, with the reefs in Kaneto Shindo's “Onibaba.”(a hopeless place that provides the sole source of hope for the lost characters) It is also worth mentioning that the narrative includes a number of interviews with the protagonists that shed light to their actual circumstances and characters, and a small number of flashbacks that are concluded during the finale. All of the above elements are implemented quite nicely in the film through Tsuyoshi Imai's editing, who retains the usual, relatively slow pace of the Japanese drama.

The only fault I found in the narrative is one of the most common ones in the country's films, of lagging during the finale, which extends beyond its (narrative) purpose for no apparent reason.

The representation of the era is exceptional, as it extends to clothes (particularly in Fumi Nikaido ), music, TV programs, tendencies and even behaviors, with Takahisa Taguchi, Naoki Soma and Masumi Sugimoto doing a great job in production design, art direction and costume design, respectively.

The acting is also on a very high level, with Fumi Nikaido being great as Haruna, Ryo Yoshizawa as Ichiro and Sumire as Kozue highlighting their detachment with elaborateness and maturity, with their acting finding its exact opposite in the excessiveness of Shuhei Uesugi as Kannonzaki, Shiro Doi as Rumi and Aoi Morikawa as Kanna. This antithesis forms one of the greatest assets of the film, as it highlights the chemistry of the cast.

“River's Edge” provides a very rewarding cinematic experience through its band of antiheroes, the presentation of the era and the depiction of the consequences of the lack of guidance from parents and teachers.