Acclaimed documentary filmmaker Kazuo Hara is currently touring his 2017 film “Sennan Asbestos Disaster,” a somber 3.5-hour long investigation of Asbestos poisoning in Japan. It is Hara's first film in 10 years.

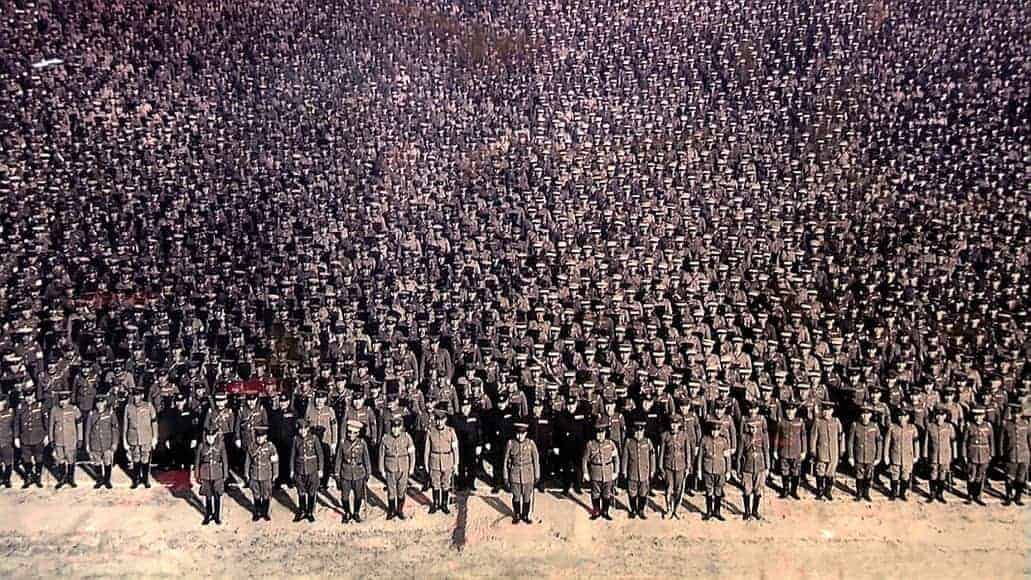

Hara is perhaps best known for his internationally acclaimed film “The Emperor's Naked Army Marches On” (1987), which unveils Japanese cannibalism during the Pacific War. The filmmaker is no stranger to controversy: in his debut “Goodbye CP,” Hara follows an activist-poet with Cerebral Palsy; in “Extreme Private Eros: Love Song 1974,” Hara turns the camera on himself and his ex-lover, even filming her giving birth to their child.

Compared to such early experiments, “Sennan Asbestos Disaster” is more tame and thoughtful, yet no less political. It chronicles 8.5 years of struggle, as former asbestos factory workers, mostly centered around Sennan, Japan, fight for reparations from the government. The victims are largely elderly or middle aged, and most have worked in asbestos factories. Hara gives these older folk breathing room to narrate at their own pace; where a more pragmatic director would have edited a 15-minute interview into shorter clips, Hara allows his subjects time to speak of a variety of topics only nominally related to asbestos. Their faces are frequently shot in close-up, providing an extremely intimate viewing experience.

However, a few scenes later, many of them die of asbestos-related causes such as lung cancer or mesothelioma. Their deaths send a shock reverberating through the audience, who have just been charmed by the victims' candor, humor, and rambling non-sequiturs. Asbestos is a known human carcinogen, and particularly lethal for those who encounter it daily. Because its protagonists are almost all suffering from serious health ailments, the film projects extreme timeliness: we never know whether one or another protagonist will pass away, becoming another statistic of Japanese pollution crises.

Thus the film gathers a sense of urgency in its second half, as the victims organize—often using extreme guerrilla tactics—to demand reparations from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. The government workers presented are often comically young and humorously evasive in their tactics. While often droll and absurdist, this observational segment reveals the alarming collusion between the Japanese government and the forces of the capital. Hara's fly-on-the-wall footage shows the fundamentally undemocratic nature of this labyrinthine process.

Hara's films often center on controversial and charismatic personalities; in “Sennan Asbestos Disaster,” this role is filled by Kazuyoshi Yuoka, a leader of the citizen's group whose father owned an asbestos factory. Yuoka frequently commands screen presence as the most outwardly enraged senior citizen. His outbursts are fueled by both fury and a sense of guilt. Yet unlike Okuzaki of “Emperor's Naked Army,” Yuoka is less an individualistic outlier than a particularly vocal group member. He takes the back seat to others' stories, and the film remains focused on collective, rather than individual, experience.

The film sees an immediate parallel with Noriaki Tsuchimoto's films, such as “Minamata: The Victims and Their World” (1971), which chronicled Japanese mercury poisoning in Minamata Bay. Like Tsuchimoto, Hara focuses on interviews with the victims of severe environmental poisoning and pollution, caused by unfettered capitalism. Just as in Minamata, in Sennan, the victims of Asbestos poisoning are in the lowest rungs of Japanese society: many are Koreans (Zainichi Chosen-jin) or Hisabetsu Burakumin, the lowest caste of Japanese citizenry, similar to Indian untouchables. And, like Tsuchimoto, Hara does not attempt an objective analysis of political affairs.

Instead, Hara's camera is always aligned with the victims of capital and empire. For this reason, his films are often compared with those of Michael Moore. This is no accident: Moore was extremely influenced by Hara's confrontational style of filmmaking, even claiming that a screening of Hara's “The Emperor's Naked Army Marches On” gave him the courage to continue production on his first film “Roger & Me” (1989), which chronicled the decline of his hometown Flint, Michigan.

Unlike Moore's films, however, Hara has difficulty paring down the film towards a more viewer-friendly structure. While the film is immensely informative and never dull, its 215-minute run time—usually necessitating an intermission—will inevitably limit the film's popularity. The film's need for further editing is its only substantial drawback, as it is otherwise an immensely ethical and important documentary feature. Indeed, the film even has uncanny relevance to contemporary American politics: just two weeks after the North American premiere of “Sennan Asbestos Disaster” at the Japan Cuts festival in New York, Donald Trump's Environmental Protection Agency approved new usage for asbestos in manufacturing. Consequently, one can only hope that viewers flock to see this rare Japanese documentary in theatres, before we allow governments to repeat their own mistakes.