“The last thing I hate is that life always forces us to keep moving forwards.”

In the aftermath of the New York Film Festival, reporter Vincent Canby wrote an article about the films of the festival he aptly named “Why Some Films Don't Travel Well”. Works such as Zhang Yimou's “Red Sorghum”, Andrei Konchalovsky's “Asya's Happiness” and Hou Hsiao-Hsien's “Daughter of the Nile” are mostly relevant thanks to their “sociology factor” Canby begins his article, an aspect that these works are and have been applauded for around the world while as films themselves they are not that interesting. Hou Hsiao-Hien, one of the most popular directors of Taiwanese New Cinema along with Edward Yang, was still trying to find a cinematic language for his films, one which strongly resembled the works of Yasujiro Ozu in terms of style and content, the sense of resignation, as he writes in another review of the film from the same year.

Buy This Title

Canby's view on the film might just be one of the best representation of how “Daughter of the Nile” has been perceived within the film community in general. Hsien himself has also supported a certain view on the film, as he has repeatedly distanced himself from it, calling it a “pop-star vehicle” (Michael Joshua Rowin) for its main star singer Lin Yang. Even in his notes on the film, one can not deny the impression of Hsien being somewhat detached towards his film, one which fills a gap between two of his most important works, “Dust in the Wind” (1986) and “A City of Sadness” (1989). Much like Canby, Hsien also stresses how he regards the film as an image of the social and cultural changes of his home country Taiwan, the influence of Western and youth culture.

However, as scholar Tony Rayns point out, “Daughter of the Nile” is significant for many reasons besides its status as a “transitional film” for its director. Hsien himself has remarked on his aim for the film to contain a balance between form and content, an aspect he felt was missing or was not that significant in his previous films. Besides these points, New Cinema has always been defined by its social agenda, its realistic style creating an important change in comparison to the more popular melodrama and action film Taiwan's film industry was known for. According to Tony Rayns, Yang and Hsien have been attacked by critics more than once of being too “self indulgent” in their works, a criticism the latter took to heart leading to the creation of “Daughter of the Nile” as something of a response to these voices.

Lin Hsiao-yang (Lin Yang) lives with her family on the outskirts of Taipei making a living with her job as waitress in a fast-food restaurant while her older brother Lin Hsiao-fang (Jack Kao) makes money through petty crimes as well as a night club he opened with one of his childhood friends. As the family tries to make ends meet after the death of the mother, Hsiao-fang and Hsiao-Yang grow more and more distanced toward the family routine in which their father is nearly always absent and their grandfather pays a visit to only once in a while.

Since their circles of friends are falling apart for many have moved away or even immigrated to other countries, brother and sister dream of making a different life for themselves, different to those lives they know from their parents. While Hsiao-Yang saves her money from work and attends night school, her brother's criminal activities increase, making him a target for other gangs within the city.

One of the first themes, visually and thematically, established in “Daughter of the Nile” is the three spheres in which the young characters move within: the domestic, the urban and the escapist sphere. Since the first two are linked to parts of the world, or their environment, which Hsiao-fang and her brother are either deeply estranged to or repulsed by the third sphere offers something of a temporary, but safe refuge. The rarity of these occasions, when the young characters get together forming their “gangs”, as they take a trip to the beach or drive side by side on a nighty motorway is stressed through the use of Western pop music, the use of light and the idealizing eye of Chen Huai-wen's camera. One is hard-pressed when trying to find an Ozu-like influence or style within these scenes as Victor Canby states, one which is perhaps only existent in the scenes taking place within the family home, emphasizing the feeling of imprisonment and stuffiness of parental attitudes. If one wants to find any kind of influence, many of the these particular scenes focusing mainly on the young share a sense of the Nouvelle Vague films like “The 400 Blows” or “A bout de souffle”.

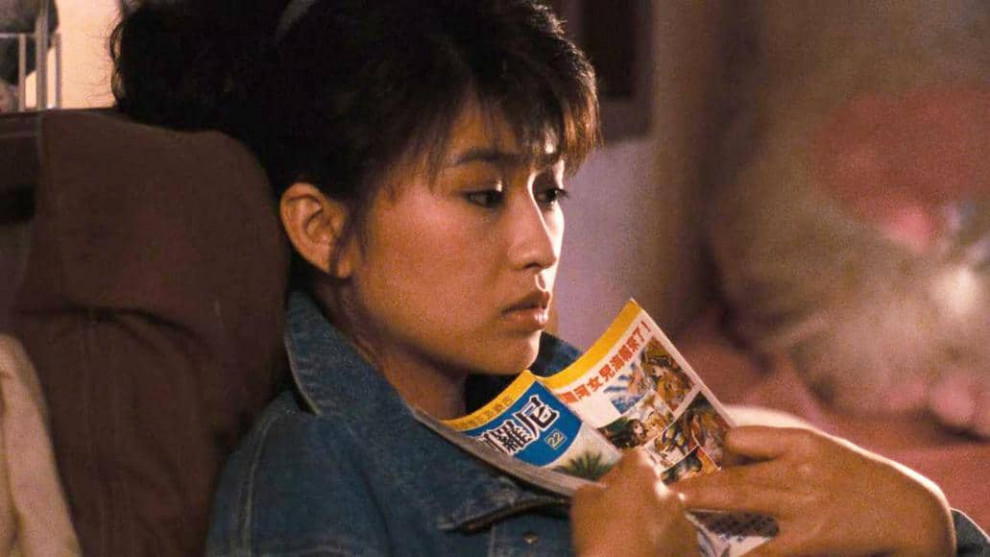

Similar to Godard's or Truffaut's protagonists, Hsien's characters have a sense of being lost, of being “orphans of the world” (Vivian Huang) trying to make sense of their time, their place and most of all their lives on their own without the perhaps much needed support of a role model older than them. Even though their level of community includes the almost obligatory number of teenage poses, especially for the males wearing sunglasses and suits as necessary ingredients for their “tough guy”-image, these are not difficult to be revealed as disguises for the kind of refuge or indeed life these characters try to define for themselves. Jack Kao plays a character whose almost destructive drive to steal is seemingly at odds with his image as serious restaurant owner, while also enabling him to share a certain, albeit stolen wealth with his family, a sense of connecting with a more Westernized culture which is economically out of reach for them or maybe even unwanted by their parents. In one of the most telling scenes between him and his father, Hsiao-fang has just introduced his fiancee to his family followed by a scene in which both men watch cartoon on television, an activity only interrupted by a short approval by the patriarch, of the woman he has chosen before delving right back into the world of the cartoon and the can of beer in front of him. At the same time, his sister's ritual of listening to music, delving into the melodramatic world of her favorite manga “Crest of the Royal Family: – the work which gave Hsien not only the title for his film but also part of its thematic foundation – as well as her predilection to spend time with her friends rather than at home speaks volumes about her level of detachment towards parental values.

Before we should take another look at this inspiration for the film, one of the most striking audiovisual themes of “Daughter of the Nile” has to be the significant Western influence on Taiwanese culture. Whereas the family home is not only geographically but also culturally different to the urban sphere – to quote Canby much like the urban/rural dichotomy Yasujiro Ozu's films are known for – the city of Taipei, whose first image is its skyline as seen by Hsiao-yang from the outside of her family's home. Even though her voice-over confirms the city as place of longing, of meeting friends, of going to parties and celebrating life, the more the films progresses the more threatening the neon lights of the city becomes. Although certain architectural details reveal the Asian foundation, the existence of KFC logos, Coca-Cola signs and other Western insignia might indicate a degree of cultural imperialism, albeit one which has become absorbed and accepted through the generations Hsiao-yang and her brother belong to. In fact, the prospect of becoming more implicated seems rather attractive to some degree, even though those of her friends who have been to West have not exactly “success stories” to tell.

Much like the aforementioned escapist fantasies of the manga, the stories American pop music has to tell in combination with moments of togetherness constitute the third sphere, one whose importance becomes more and more imminent as the film goes on and the other sphere become increasingly more hostile and violent. Besides the fictional world being a “time machine” (Hsien) for the female protagonist, the narrative provides a more simplified version of a reality, an escapist melodrama in which the males were the “makers” while women would tend to them and their needs (Rayns). Considering his country's almost historic attraction towards these kinds of narratives as mentioned before, one might regard a reading such as this as Hsien making an ironic statement; however, within the context of the film's story, the irony will leave a bitter aftertaste since shrugging those fantasies off as mere escapist refuges denies the increasing comfort they might provide as the protagonist's reality slowly deteriorates.

Much like the voice-over, Hsiao-yang telling her own story, or rather her memories, also indicates a need to control the progress of time, events carrying the patina of the past, of nostalgia, like images in a picture book. As shown in the aforementioned scenes on the beach or on the motorway, the amber-colored quality of these memories show rare images one likes to go back to, as if turning back time similar to the heroine in the manga, but also represent the fear of how time, life and people will eventually move on.

“Daughter of the Nile” is a film about young people trying to find their version of life, their definition of culture somewhere between ideals of the past and the more attractive present. It is a movie which carries a distinct notion of these events being unique in the way the will never comes back, but having been repeatedly looked at like pictures in a photo album, an awareness of time moving on an events destroying any sense of idyll or happiness one has build for himself, whether it is an escapist fantasy or a more grounded sense of togetherness when starting a business with friends. In the end, just like the teenage protagonists of Godard and Truffaut these “orphans of the world” also carry a sense of doom with them, a feeling that all of this is just temporary.

Sources:

1) Huang, Vivian, Hou Hsiao-Hien – Director

www.filmreference.com/Directors-Ha-Ji/Hou-Hsiao-Hsien.html, last accessed on: 03/14/2018

2) Rowin, Michael Joshua (2008) Lost City. Michael Joshua Rowin on Daughter of the Nile

reverseshot.org/symposiums/entry/616/daughter_nile, last accessed on: 03/14/2018

3) Canby, Vincent (1988) Rootless in Americanized Taiwan

www.nytimes.com/1988/09/30/movies/rootless-in-americanized-taiwan.html?sec=&spon=, last accessed on: 03/14/2018

4) Canby, Vincent (1988) Film View; Why Some Movies Don't Travel Well

www.nytimes.com/1988/10/23/movies/film-view-why-some-movies-don-t-travel-well.html?sec=&spon=&scp=7&sq=DAUGHTER%20OF%20THE%20NILE&st=cse&pagewanted=2,last accessed on: 03/14/2018

5) Hoberman, J. (2017) ‘Daughter of the Nile': Baffling, Beautiful and Newly Restored

www.nytimes.com/2017/10/24/movies/daughter-of-the-nile-hou-hsiao-hsien-quad-cinema.html, last accessed on: 03/14/2018

6) Chan, Andrew (2017) Review: Daughter of the Nile

www.filmcomment.com/article/review-daughter-of-the-nile-hou-hsiao-hsien/, last accessed on: 03/14/2018

7) Tony Rayns on Hou Hsiao-Hsien and Daughter of the Nile (2017)

8) The Director's Note as well as the Director's Statement are part of the Blu-ray release of the film through Eureka!