Probably one of the best independent Indian films of the year, Devashish Makhija's “Ajji” takes a dark (noir) approach to the “Red Riding Hood” fairytale, by placing it in the Indian slums and inducing it with violence to the point of gore, and a number of pointy social remarks.

When little Manda fails to show up after being sent for a small chore in the night, her grandmother and a local prostitute begin to search for her, only to find her raped and dumped in a trash heap in her slum. As soon as they arrive home, the family informs Dastur, the local policeman of the sexual assault, with the girl almost immediately identifying the perpetrator as Dhavle, the son of the local governor. However, Dastur is not only unwilling to help, but actually threatens them to drop the whole thing, by hinting on the fact that Manda's parents have illegal jobs. The two of them do not seem to have the will to resist to his threats, but the same does not apply to Granny (ajji), who immediately embarks on an intricate path of revenge, starting to watch Dhavle from the shadows and asking a butcher friend of hers to teach her how to cut up meat. Her plan though, is much extremer than anyone imagined.

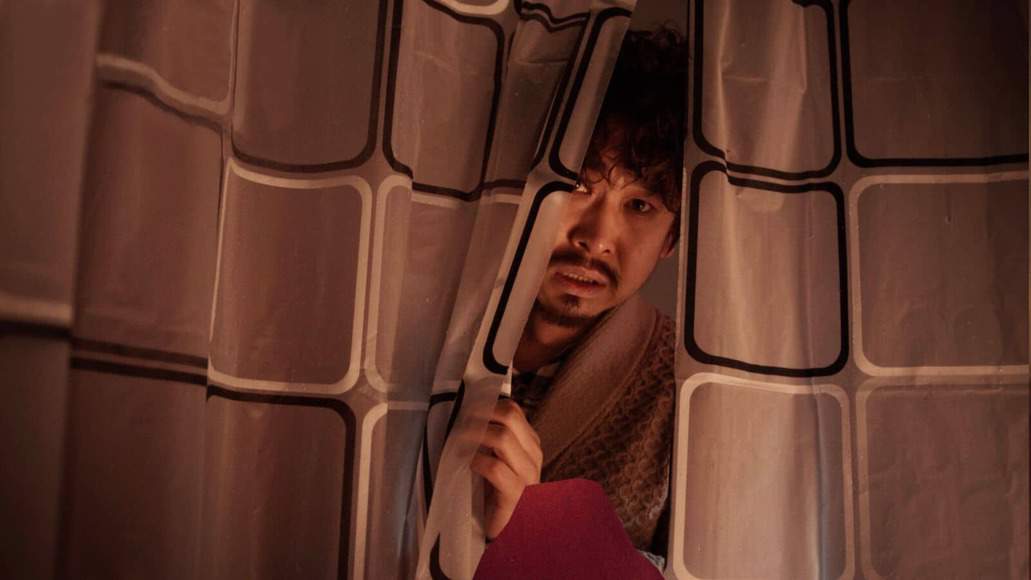

Devashish Makhija draws some elements from Red Riding Hood, particularly since Dhavle is, quite obviously, the big bad wolf, to present a revenge film with social implications. However, this is not just another entry in the category, for a number of reasons. To start with, Makhija uses noir aesthetics, as the majority of the story takes place during the night, with Jishnu Bhattacharjee's cinematography and Mangesh Dhakde's music implementing the dark aesthetics of the genre in impressive fashion. This noir essence is strengthened further by a number of shots that allow the audience to feel as if they are picking on the events, just as Ajji does from the shadows.

The second reason is the social remarks, which extend in two axes: The corruption of power and the ties of politicians and “the capital” with the police, and the fact that everyone expects from the elderly, and particularly women, to be docile, helpless and obedient, and actually just to sit and wait to die. Makhija goes completely against the last “belief” by having an elderly woman who goes to extremes to avenge her granddaughter, as his protagonist.

The third one is the fact that he does not shy away from violence in both its consequences (with the psychological and physical traumas the girl suffers after the assault being presented with almost brutal realism) and its implementation, with the approach finding its apogee in the finale. The same applies to the perverse sexual tendencies of Dhavle, through which Makish paints the portrait of a truly despicable man.

The fourth one is the fact that the movie seems to justify the vigilante ways of Ajji, in the process showing that revenge can be the only way one can get justice in a society where the opposite is the norm, particularly when the rich are the perpetrators and the poor the victims.

The narrative of the movie is impressive (although the script takes some creative freedoms), as it parallels with Ajji's preparations for revenge, with only a few breaks where Makhija reveals Dhavle's character, and some flashbacks of the relationship the girl had with her grandmother before the incident. In this, (almost completely) linear progress, Makhija has included a number of scenes that will definitely stay in the memory of the spectator. The visit of the policeman in the house in the beginning, the scene with the plastic doll, the ones where Ajji is cutting meat, the one where the girl talks about blood, the one where Dhavle and Mastur meet, and the finale, are as shocking as they are artful, strengthening the impact of the film even more. Mangesh Dhakde's music also finds its apogee in these sequences, as it highlights the sense the director wants to give to each one, with the track included in the scene where Dhavle and Mastur meet being the most memorable, filling the scene with a sense of danger emitting from the latter.

The acting is also on a very high level. Sushama Deshpande as Ajji gives a magnificent performance that demands from her to appear silent and extremely tired, but also extremely resolved and dedicated to her purpose. Abhishek Banerjee as Dhavle plays the archetype of the despicable villain with a very fitting notoriety, while Vikas Kumar as Dastur is very convincing as the corrupt “servant” of the rich, with his behaviour being radically different when dealing with each. Lastly, Sudhir Pandey as the red-bearded butcher is a truly cult figure in the film, that fits the exploitation elements to perfection

“Ajji” is a great film that manages to combine the revenge thriller with the noir and the exploitation film, through a no-punches-pulled presentation of a theme with social implications.