“Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji” is a significant entry in the filmography of Tomu Uchida, one of the most important figures of the Japanese pre-war cinema. The film signaled his return to cinema after spending a decade in Manchuria while it is also considered as both a harsh political statement and a tribute to Uchida's friend, Sadao Yamanaka, a promising director who was killed in combat in Manchuria. Furthermore, the film is a rare case where shomin-geki is combined with chanbara, since Uchida uses the samurai setting to portray, realistically, the lives of the lower castes in Japan, through a production that functions much like a road movie.

Buy This Title

Sakawa is a kind samurai who travels to Edo to present some valuable ceramics to his mother. He is attended by his two servants, Gonpachi, a proud and selfless samurai who functions as his spear bearer, and Genta, who is more self-indulging and frequently gets scolded by his senior. The two servants also have an additional mission, of keeping their master away from alcohol, which totally changes his character, making him quite obnoxious and troublesome whenever he gets drunk.

Gonpachi meets a boy in the road, Jiro, and takes him after his wing, when the boy states that he also wants to become a spear-bearer. As their travel continues, they also come across a traveling singer with her child, a father taking his daughter to be sold into prostitution, a pilgrim, a policeman searching for a notorious thief, and Tozaburo, the suspicious man the officer has his eyes on. The film begins as a comedy, but as time passes and the secrets of the various characters are revealed, it takes a rather dramatic turn.

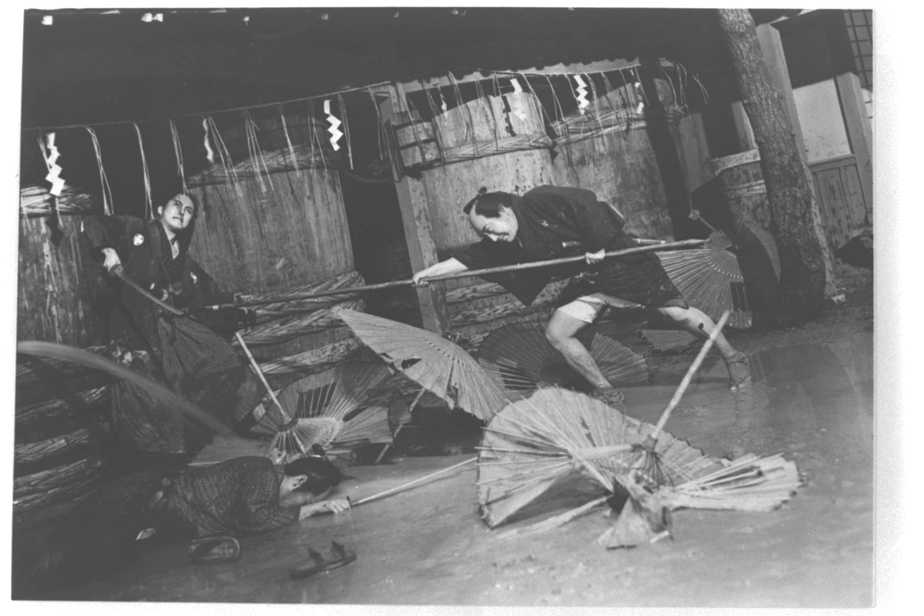

The aforementioned combination of shomin-geki and chanbara derives from three factors. The first one is that the actual protagonist is Gonpachi, a servant, (a concept falling under the shomin-geki) instead of Sakawa, the samurai, as was the usual case in films of the second category. The depiction of the lives of the poor and the struggles they had to face, even having to give up their children to make a living, is the second factor. The third one derives from the realism in the presentation of the samurai era, with Uchida making a point of highlighting the fact that the samurais were not the glorified heroes the chanbara films usually presented, but people with many faults who occasionally relied extensively to the people around them, even receiving the laurels for their actions. The finale of the film, which is filled with action in distinct chanbara fashion, also presents the fact, in probably the most obvious way in the whole film.

Apart from the social drama and the various socioeconomic comments, Uchida also focuses on the entertainment aspect, through a number of comic episodes (the one with the kid's stomachache and the tea ceremony will definitely make the spectator laugh) and the various action scenes. The second aspect is presented mainly towards the ending of the film, with the final scene providing the most impressive sequence in the movie.

In order to present all the aforementioned, Uchida gives his narrative an episodic nature, which follows the “rules” of the road movie, with many characters involved in a number of episodes revolving around the main protagonists.

Sadatsugu Uchida's cinematography embodies the aforementioned elements fully, particularly because the depiction of the samurai and the common people is the same, thus retaining the aforementioned comment regarding the samurai and their servants in visual terms also. His focus is on realism, although the depiction of the final battle is also induced with epic elements

Chiezo Kataoka as Genpachi is great as the embodiment of Bushido, despite his position, with him presenting a character full of virtue, who finds himself, though, having failed in the thing he considered the most important in his life. His son, Motoharu Ueki plays Ichiro and he is a delight as a loud, troublesome boy, with the chemistry with his actual father being one of the film's best assets, while the ending, that features just the two of them, makes the most significant comment in the film, regarding the samurai. Kataoka's daughter, Chie Ueki, also plays a part, as the daughter of the traveling singer, with the two of them taking part in one of the most beautiful scenes in the film, where the mother sings and plays the samisen and the daughter performs. Daisuke Kato as Genta was the one who received an award for his performance though, from Blue Ribbon, with his performance as the “clown” being quite entertaining.

“Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji” is a great film, as it presents a different take on the samurai concept and a number of social comments, while retaining its entertainment values at all times.