“It is inside of me and yet I do not know what kind of feeling it may be.”

2004 was a slow year given the usual pace of Japanese director Takashi Miike with his feature Zebraman and the impressive segment “Box” for the “Three…Extremes”- anthology. Perhaps given the last feature released that year it might shed some light on the a longer and quite ambitious production,a which was quite unusual considering the companies supporting “Izo”, as distributor KSS and Excellent Film, as author Tom Mes explains, had earned their reputation by “churning out” V-cinema productions, most of which have been, probably rightfully, forgotten.

“Izo”, however, was quite different for the companies, similar to the status it holds among Takashi Miike's body of work. Uniting two heavyweights in Japanese culture, Takeshi Kitano in a minor role and Takashi Miike in the director's chair, the film which centered around the character of Okada Izō, a feared assassin who was executed in 1865, touches upon subjects ranging from Japanese history to Buddhism. The script by one of Miike's frequent collaborators, Shigenori Takechi, who also wrote the script for “Graveyard of Honor”, “Agitator” and “Deadly Outlaw Rekka”, was a project Miike presumably could not say no to. With its loose structure and the sociopolitical foundation which had already added its share to the grim and dark mood of “Graveyard of Honor”, “Izo” was a project which would fit right within Miike's qualities, as well as present an opportunity to expand on some of those themes.

Buy This Title

“Izo” is a film about the nature of man linked to the history of violence in the world. Based more on a thesis, it asks the question whether man can break the cycle of violence once it has started and if indeed, life without this aspect is even possible.

Izo (Kazuya Nakayama) is executed after having killed hundreds of men in service of the Shogunate, obeying the order of his lord Hanpeita (Ryosuke Miki) to kill as many of them as possible. Through the sheer power of his rage he is resurrected in present day Tokyo, an event which brings him the attention of the intellectual, political and military elite of the nation led by the Prime Minister (Takeshi Kitano), who plan to do everything in their power to stop the absurd entity which is Izo.

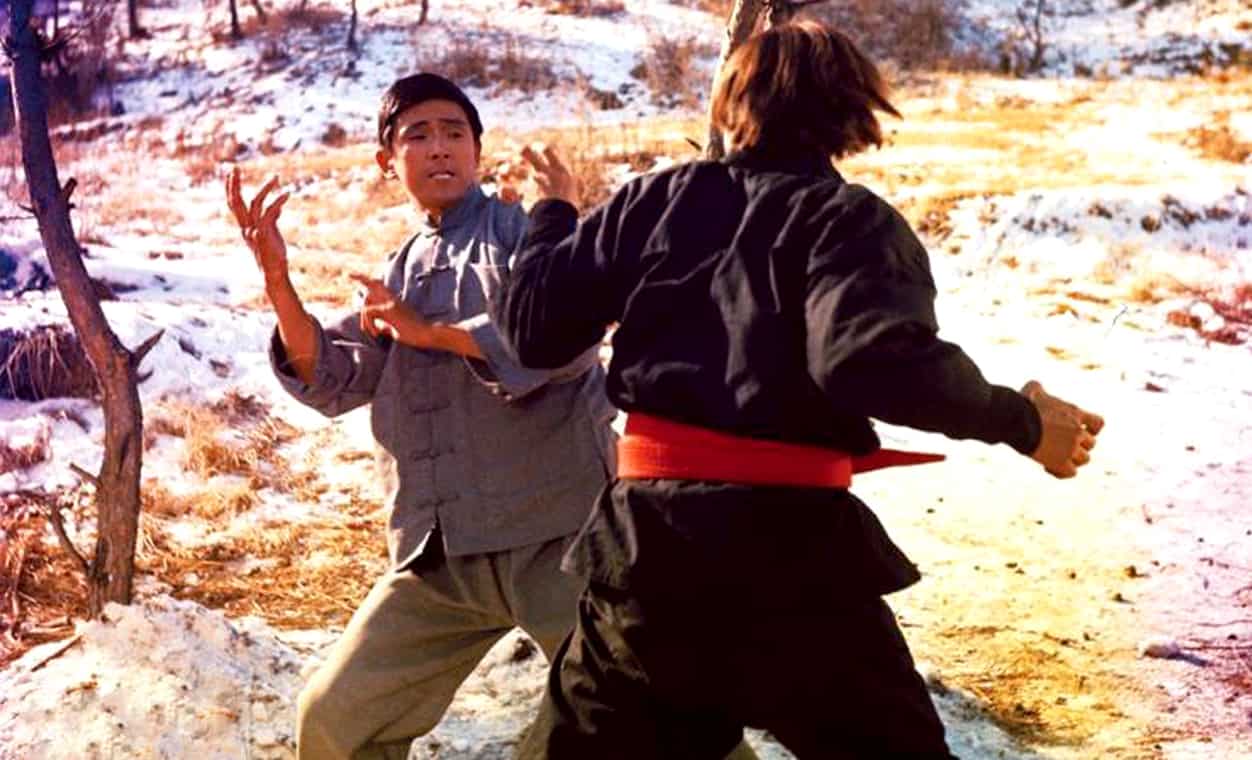

As he makes his way through wave after wave of attackers, Izo repeatedly breaks the borders of time fighting warriors in ancient Japan or street gangs in the present. On his journey, he is also confronted with the victims of his past crimes, those vengeful ghosts ready to prolong the suffering Izo goes through whose lust for blood slowly but surely transforms him into something close to a devil.

In the last scene of “Graveyard of Honor”, a film which can be regarded in many ways as the thematic precursor for “Izo”, the Super 8-footage shows Ishimatsu with his two loyal friends while they were still a team, loyal to each other and not determined by self-destructive forces which inevitably, as the film has shown, come as defining forces not just for within the hierarchy of the yakuza, but also as character traits of their environment and, above, almost as their human core. Fittingly, “Izo” starts with a collage of footage taken from sex education videos, promotional material for theme parks and of war times which immediately leads to the core of the film, to the thesis the rest of the over two hours of running time will be dealing with, how violence and destruction are determining factors of human existence. With birth, as the collage presumably tells us, the lust for these concepts is inherent in the genetic code of mankind, passed on from generation to generation like the footage of wars from different eras of history and countries might suggest.

And considering war is a repeating factor in human existence and history, violence and destruction are part of the endless stream of time which is now the path the central character walks on. The character played by actor Kazuya Nakayama is in many ways an unlikely figure to place in the center of a movie, as it is made clear from the start he is a mere soldier in the service of a lord giving him the simple order to just kill and never stop, a command he accepts without protest nor any other signs of grief or anger. Similar to many of his opponents calling his quest “absurd” or “nonsensical” any viewer will have some difficulty in the walking contradiction which is Izo who obeys, is shoved around by opponents, and forces of time and place, as well with the only constant link between all settings, the never-ending flow of sword fights.

Being the perfect outcast, a theme which has become central in Miike's body of work, he is not only shunned by society but actively seeks to make this condition, complete rejecting notions of nationality, religion and authority since those are mere opponents in his way. However, in a fight which has become increasingly pointless since he is unable to die and therefore is victorious in all of the fights in the film (which is pretty much clear after 15 minutes into the story) there is also a contradiction at the core of the film whose stance as being anti-ideological is in essence an ideology imposed on this character. The only problem is Izo, as he is told repeatedly, does not follow anyone or anything, except for the notion of killing humans and other forces in his way. Considering this structure, “Izo” might just be one of the most difficult viewing experiences within Miike's body of work, one which even Tom Mes, usually a vocal supporter of the director's work, has a hard time defending, especially against criticisms of being “repetitive”, “ponderous” and “pretentious”.

Coming back to the notion of violence and destruction as defining forces, “Izo”‘s structure as well as the transformation of the character follows the principle of numbing the viewer until he/she arrives at the same conclusion as Izo's various opponents and other people he encounters. The repetitive nature of the fight scenes, whose point has been erased with the fact Izo is unable to die, is stressed by Miike's almost improvised-looking way of shooting these scenes and choreographing them, a concept he would bring to perfection in later films like “13 Assassins” and “Blade of the Immortal”. As writer Ben Sachs writes in his review of the film, these scenes are quite “boring”, but in the context of war as never-ending cycle at least the approach of script and director makes sense. By the times one has seen the fourth or fifth of these fights, one has not only understood the constant pain of the character as emphasized by his hoarse screams when wounded or killing his opponent but also the pointlessness of these acts of violence. In the end, the logical conclusion is to come to break this cycle, but just like a Hydra, if one head is chopped off, others will shortly grow back and the fight begins anew.

Technically, “Izo” stays true to the visual form of the collage as introduced in the aforementioned opening with styles and pace changing as the movie switches settings every so often. As is following dream logic classical chanbara-like sequences will be followed by scenes reminiscent of the yakuza-genre. One of the most significant features is the score by musician and poet Kazuki Tomokawa, whose songs of about grief and loss echo the same questions for the purpose of these wars, conflicts and acts of cruelty committed by Izo and those he fights against.

“Izo” is a difficult film in many ways. While the themes of the movie show a commitment and courage on the side of those involved, its repetitive structure will likely irritate even the most loyal followers of Miike. At the same time it shows a director making a statement about the bleakness within the world, the never-ending cycle of violence linked not just to his home country but to the whole world. Because in the end, war or conflict has no winners, not even those who are above death and time. Eventually everyone screams.

Sources:

1) Mes, Tom (2013) Re-Agitator. A Decade of Writing on Takashi Miike. FAB Press

2) Sachs, Ben (2010) A Decade With Takashi Miike. Unwatchable, Essential: “Izo” (2004)

https://mubi.com/de/notebook/posts/a-decade-with-takashi-miike-unwatchable-essential-izo-2004, last accessed on: 01/31/3018