Iyamisu is a subgenre of mystery fiction, which deals with grisly episodes and the dark side of human nature. The subgenre has been quite popular recently in Japan, particularly through the works of Mahokaru Numata, Kanae Minato and Yukiko Mari. Inevitably, it also found its way into the cinematic world, with films such as Minato's “Confessions” and Numata's “Birds Without Names”.

Birds Without Names is screening at Five Flavours

Towako lives an aimless life. She is still stuck thinking about her ex-boyfriend, Kurosaki, even though they have broken up 8 years ago, and despite the awful things he did to her, including a severe beating upon their break up. She lives with a man named Jinji, a worker who is 15 years older than she is, and whom she actually despises, constantly putting him down and slamming him verbally for his “vulgar” ways. The only reason she lives with him is that he is the only source of income in her life. Jinji, however, loves her passionately, and is willing to do anything for her, not bothering to ask the slightest thing in return. One day, Towako meets Mizushima, a watches salesman who reminds her of Kurosaki, and starts an affair with him, despite the fact that he has a wife and children. Soon after, a detective visits Towako and tells her Kurosaki is missing.

Kazuya Shiraishi directs a film where tension dominates the narrative. There is a tension in the way Towako interacts with the people around her, including various shop clerks, her constantly worrying sister, Jinji, and even when she is just by herself. Quite early in the film, it becomes apparent that this tension derives from events that happened in the past, which the “couple” thoroughly avoids referring to, with the mystery of whose secret it is and what exactly is about, actually carrying the film until the plethora of revelations that come up in the last 45 minutes or so, after the family dinner scene, which I felt is the most tense in the movie. These events provide quite impactful plot twists, which give the film its crime/mystery nature.

This last aspect, however, is not the main one, as Shiraishi's main focus lies with the abnormal (dysfunctional or even perverted if you prefer) love relationships of Towako. First, there is her past relationship with Kurosaki, a highly abusive one towards her, both mentally and physically, which she, however, cannot seem to get over from, to the point of a destructive obsession.

The second, and the most central one, is the one with Jinji, which is also highly abusive, this time on her part. In that fashion, Jinji has to endure verbal and physical abuse and a number of almost constant harsh behaviors, with Towoko repeatedly making evident that she is with him only to exploit him. I found that her behaviour find its apogee in their “sexual” endeavors, with Towako rejecting harshly any progressions of his, but actually welcoming them when she is in the “mood”, which, even worse, derives from her sexual desire for another man. The fact that he does not seem to mind at all of her behaviour, instead reacting with a slaving kindness, seems even more abnormal than Towako's obsession with Kurosaki. This element becomes even more intense as the story progresses, finding its apogee in the finale, which also provides a rather eloquent answer to the questions “why does he endure all this” and subsequently, “Is this real love?”

The third one is the one with Mizushima, a mostly sexual one that highlights both the counterparts' despicability (since they are both in relationships) and their superficiality, as it becomes obvious that they are together just because they are attracted physically to each other. This relationship, however, provides two catalyst moments for the story. The first one comes up when Mizushima begins talking about Taklimakan, the Uyghur concept of eternal death, in a conversation that ends up making obvious how lonely Towako feels. The second one comes later in the movie and is the one that begins the final part, through its violence.

Violence is actually one of the central elements of the narrative, with it deriving almost from every interaction in the film, although its form is as underlying as it is visual, with the palpability, however, being apparent at all times. The other central element is eroticism, which takes “abnormal” (exploitative if you prefer) forms as much as normal ones. In that regard, Shiraishi exploits the physical appearance of his cast as much as possible, without showing almost nudity, though. Particularly Yu Aoi , Tori Matsuzaka (who seems to have taken the role of the sex symbol lately with his appearances in “Call Boy” and “The Blood of the Wolves” ) and Yutaka Takenouchi (Kurosaki), all of which could easily be super models. Sadao Abe's physical lacking in this department is another element Shiraishi exploits, further having him look dirty and ragtag at all times, in an eloquent and even extreme presentation of the concept, “the beautiful do not have to try, the ugly must at all times”.

Another main element of the film is abuse, and particularly the fact that the ones who receive it repeatedly are also bound to apply it, but even worse, that they keep craving it, in a rather harsh but also realistic comment.

The story and the character creation in the film is great, but Shiraishi's direction suffers from one of the most common “ailments” of the recent Japanese movies, that of unnecessary lagging, particularly during the ending, which I felt would be most impactful with some tighter editing. In general, though, Hitomi Kato'ss work in the department is quite good, with him implementing a relatively fast pace that suits the movie's aesthetics perfectly.

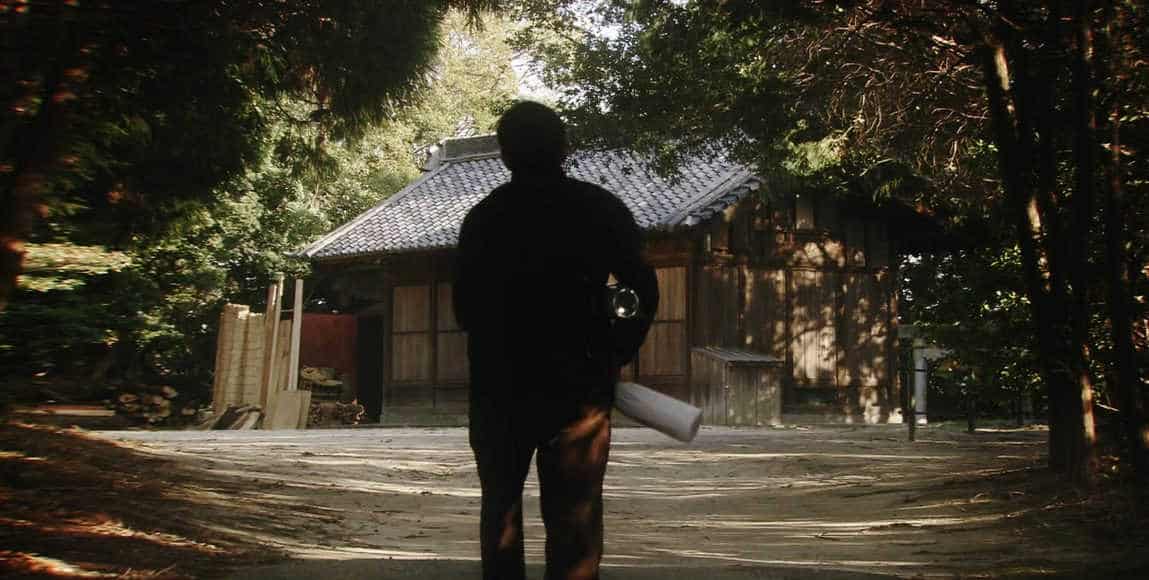

The narrative and the way it unfolds benefit the most from Takahiro Hashibara's cinematography, which gives the film an almost constant claustrophobic feeling, which finds its apogee upon Towako's visit in Kurosaki's former house. The erotic scenes are also very well-shot, with Hashibara implementing a subtle (almost no nude, as I mentioned before) approach, which derives nothing, however, from the sensualism emitted from the plethora of them.

The acting is also on a very high level. The film is obviously headed by Yu Aoi, who is great as Towako, portraying a number of changing feelings and psychological statuses, and a sense of disorientation, which, upon the revelations of its roots in the end, provides the highlight of an impressive performance. Although his role is somewhat minor when compared to Aoi's, Sadao Abe's performance is equally accomplished as a man who has dedicated his life to his love for a woman, sacrificing every part of himself in the process. Tori Matsuzaka is quite convincing as the gorgeous but quite sleazy Mizushima.

Although ailed by the common faults of recent Japanese movies (including a somewhat far-fetched script), “Birds Without Names” includes more than enough elements to erase any negative aspects, while particularly the acting and the direction have enough impact to raise it to one of the best films of the year.