“My mum never made lunch for me.”

“Who would for scum like you?”

By 1972, Kinji Fukasaku could already look back on a long career making movies for Toei studios. Additionally, his contribution to Richard Fleischer's “Tora! Tora! Tora!” (1970) marked the director's first international collaboration as he was responsible for the Japanese segment of the film together with his colleague Toshio Masuda. Even though much of his body of work consisted of contract work for the studio, many of his projects also showed signs of the kind of energy and anarchy which would constitute his later work.

On the surface “Street Mobster” sounds like the kind of movies Fukasaku had done previously. As film scholar Jasper Sharp points out, the original title of the film, “Gendai yakuza: Hitokiri yota”, signifies a shift from away from the traditional approach to the gangster genre. However, it was not until Fukasaku's final entry to the series, whose previous parts had been shot by different directors, that the term “modern” was fully implemented in terms of content and form.

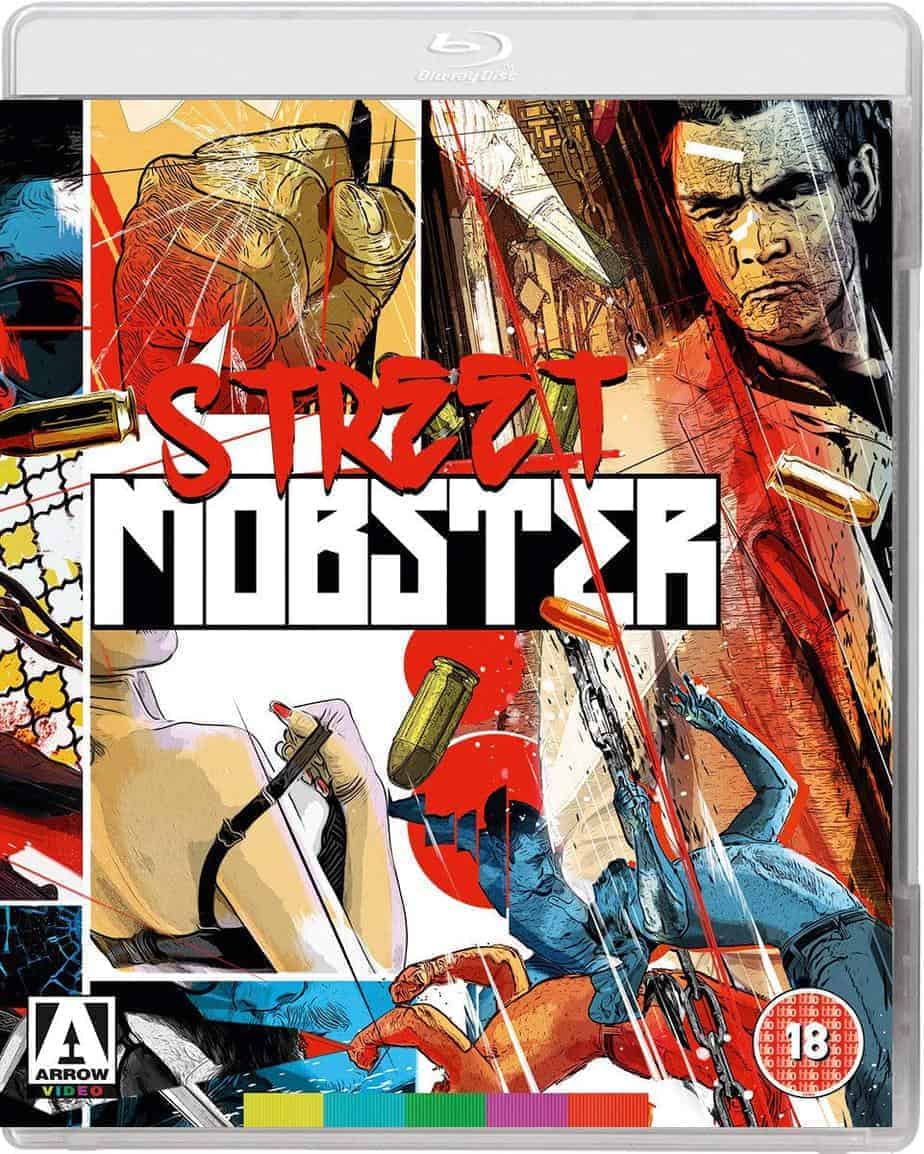

Buy This Title

Born into a broken home, Isamu Okita (Bunta Sugawara) has come to accept violence as part of life. In fact, brawls and girls have become integral parts of his everyday routine as he roams the streets of the Japanese capital with his band of loyal followers, a gang unafraid to challenge anyone stupid enough to stand in their way.

However, as Isamu is sentenced to prison after killing a rival, he spends large parts of his youth in jail. Once released, he finds out not only the world has changed, but the yakuza have taken over what has been his territory before. With the help of Kizaki (Asao Koike), he starts gathering new members for his gang, hungry for money, girls and reputation in order to take back what was once his. But as he crosses path with the powerful yakuza bosses and their families, his new gang soon finds out they have learned how to deal with punks like them.

Considering the film has the phrase “modern” in its title, the introduction of its main character and his traits could not be more fitting. In what has become a trademark for the director, the opening montage of Isamu's childhood, his relationship to his mother and his youth in street gangs does not waste time, almost attacks its audience. Given the context and the nature of the protagonist, this kind of entry into the world of the film fits quite well to the brutality of the man who openly admits he likes brawls and sex (but is unlucky when it comes to gambling). As the streets are his home, having been abandoned from home, there is no facade or mask for people like Isamu. To add to this image of the character, the blood spilled on his first murder fills the screen shaping the opening title, a birth in blood followed by a different sort of education during the time he has to go to prison.

Additionally, actor Bunta Sugawara embraces the wildness of his character in his performance. Even though his later roles, for example, in the “Battles Without Honor and Humanity”-series, would be less brutal than here, Isamu is, nevertheless, a precursor to the kind of disrespectful and impatient attitude towards the old which links these characters (and films) together. In his way of talking and his presence nothing is “fake” or dishonest, unlike the feigned smiles and gestures of the yakuza we meet in the film. It is obvious from the start his kind of wildness is exactly the reason he has a target on his back, or why he soon will become an annoyance to the business of the yakuza.

Similar to his other films, Fukasaku and his co-writer Yoshihiro Ishimatsu have an eye for the way hierarchy and business rule the masculine world of the thugs and gangsters. Despite their bonds of loyalty and the insistence of codes of honor, there is no time for heroics. In fact, people like Isamu seem to find sick pleasure in dragging others with them, soiling them and to shape them according to their amoral standards. One of his victims, a woman named Kinoyu (Mayumi Nagisa), has been raped and violated by Isamu and his gang, an event which has defined her future in the city. Being a prostitute with the same violent impulses, she is one of many victims on the path of people like Isamu. However, this kind of recklessness comes with a price in the merciless world of the yakuza, or a bullet to the head.

Stylistically, “Street Mobster” easily fits in with the aesthetics of his other works. Quick cuts, the tendency towards askew framing of shots create the perfect image of anarchy, of the order being constantly upset. Fukasaku seems to relish the chaos in his shots, which is especially true for the numerous fight scenes, stabbings and shoot-outs of the film, a breathless marathon of violence mimicking a downward spiral of violence and greed.

In conclusion, “Street Mobster” is a true Fukasaku film, offering an insight to the themes which have defined the director's work formally and narratively through his career. This is undoubtedly an important piece of work for its director, one which will certainly please fans of the genre due to its still inventive and radical ways of portraying gangsters as well as the system allowing them to flourish, to kill and to survive.

Sources:

Sharp, Jesper (2018)Mob Rules: Fukasaku's Street Mobster