“Why do all you big shots say the same stupid lines?”

Japanese director Seijun Suzuki is perhaps the greatest of all mavericks within the film industry of his country, certainly among the first voices bringing fresh ideas, images and above all a re-definition of the traditional genre the big studios like his employers at Nikkatsu churned out, year after year until the 1960s. Similar perhaps to French director Jean-Luc Godard, a comparison which is often mentioned in reviews or discussions about his body of work, his cinema, like “Branded to Kill” or “Youth of the Beast”, did not reach its audience at the time of its release, but survived over the years and have added to the reputation of Suzuki as an artist who simply grew tired of repeating the same formula because it meant a steady paycheck.

Buy This Title

According to authors Frederick Veith and Phil Kaffen, it was not until 1968 until “Youth of the Beast” was finally given the attention it deserved when student newspapers regarded the film, along with others, as symbols for the struggle against the system. This incident, along with the distinct dislike of the studio's executives of his film “Branded to Kill” (1967), led to Suzuki being fired from the studio, a development which, in retrospect could not have come at a better time, as it not only manifested the director's status as an enfant terrible of the Japanese film industry but also enabled him to rid himself of the much hated genre cinema. In the meantime, his films, like the works of the Nouvelle Vague in France, became important works within the student revolts of the 1960s, films just as revolutionary and edgy as the movies by his colleague Nagisa Oshima, another important voice of the time.

On the surface “Youth of the Beast”, based on the novel by Hyakken Uchida, is a relatively straightforward Yakuza-film with all the necessary ingredients of tough guys, drugs, violence and seductive females. However, according to critic Tony Rayns, inescapably, it is a film which already predicts the more daring experiments of its directors culminating in “Branded to Kill”, some of which he had already tried in the 27 films he did prior.

Joji (Jo Shishido) has been making a name for himself in the circles of the Yakuza, a man who will not be blackmailed and is not afraid of fighting back, no matter the consequences. His man, Hideo Notomo (Tamio Kawaji) is more interested in hiring for his clan, especially after Jo, as he likes to be called, beat up one of his soldiers. Agreeing to work for him, he befriends the simple-minded hitman Minami (Eimei Esumi) who helps him as he starts collecting money on Notomo's turf and starts fighting with the opposition.

However, he has also contacted Notomo's enemy, the Sanko group, promising them to give them the necessary information to eventually gain the upper hand in the war with their rivals, of course only for a decent paycheck. But Jo is merely disguising himself as one of them as he is set on finding out about the true murderer of his friend Takeshita (Eiji Go), someone who is part of one of these two clans and he hopes to drive out as soon as the conflict between the families escalates.

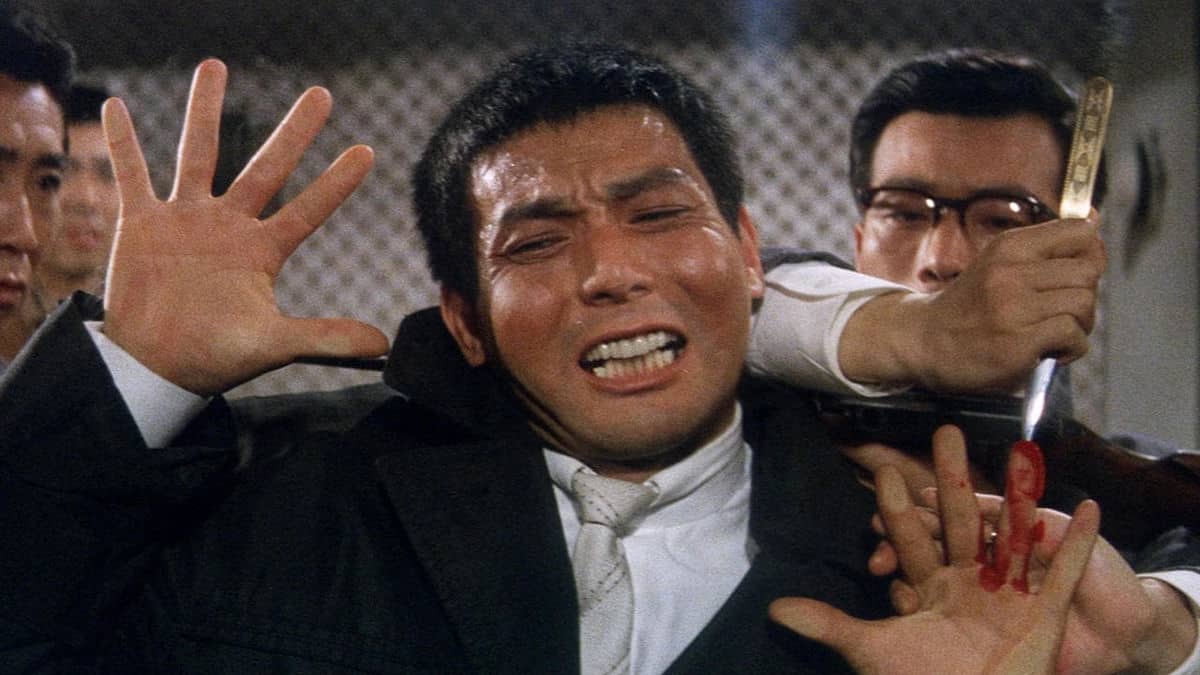

He has been ordering booze from the bar, the most expensive girls, still no one is showing their ugly face, not one of them. Hiding probably, so he has to make more of an effort to make them pay attention, roughing them up did not do the trick even though it certainly had its positives. The girls around him are talking, but he does not listen, they are also ordering more champagne, every bottle of it a monthly paycheck for some, but then again no one is going to pick up this tab, most certainly not him. After he has slipped ice cubes into the dress of one of the girls who had been the most annoying of them, finally three of them appear, expendable goons with dents in their jackets where their pistols are. They had been watching him all along, through a secret mirror, behind it a secret room, soundproof. Good, so no one else will interfere when he has a little fun with them.

In the midst of the rather generic narrative, one becomes aware of the director's intention, his attempt to play with both plot and form when we see how much of the above described scene seen from the perspective of those Yakuza hiding behind the secret mirror. The scene becomes part of a silent sketch as no sound from the restaurant can be heard, highlighting the exaggeration within the scene, the laughter, the excess, the brooding protagonist with his strange looking cheek implants giving his face a puffy look. Mirrors and glass windows are frequently used in order to stress the artificial nature of the scene, creating a sense of awareness, a meta-level in which the story of the film takes place. Some of more elaborate shots by Kazue Nagatsuka further hint at the constructed nature of the film while also expressing the willingness to experiment.

A similar awareness can be found in the dialogue as well as the acting. Jo Mizuno plays the tough guy, a playboy with a violent streak who can take and deal a vicious beating. Apart from the puffy look, his eyes seem more concentrated, focused on what his plan is, as every move of his seems to have been studied before like in a chess game. He is a man with the slightly silly one-liners, and as someone else utters them, he claims “that's my line”, somewhat angry and disappointed he was not the one who was fast enough. As lines are repeated as well as certain behavior, his status as the hero enables him to be aware, to comment on this fact even.

Following what Hasumi Shigehiko calls “surface criticism” it is not only the aspect of awareness, but rather its director's attempt to work against the generic nature of the story. Apart from the aforementioned use of camera and framing, its slow fade out of scenes or the inclusion of the comedic sidekick (Minami) falling in love at the wrong time seem like attempts to slow it down, more attempts to shake up the narration as well as its form. These are at times tiny details, for example the addition of model airplanes in the home of one Yakuza, a somewhat strange visual cue showing how behind the tough guy image there is an actual human being existing outside his role as well.

“Youth of the Beast” is an important film within the body of work of Seijun Suzuki, one which showed its director as the great inventor and experimenter of form at a time in which these kinds of surface still defined film, not only in his home country. A Yakuza- or revenge-movie on its surface, the film can be seen as a statement against conventions, conception of what genre, protagonist and plot is. On the other hand, it is an, at times, funny as well as well-acted and -photographed film from a director who clearly knows his craft and is about to perfect it.

Sources:

1) Veith, Frederick; Kaffen, Phil (2014) Seijun and the System.

2) A video interview with Tony Rayns, also included in the Bluray-relase of the film by Eureka.