[The following essay contains major spoilers.]

“I firmly believe a very Japanese film that is different from others can easily cross borders.”

(Hideo Nakata in the foreword of “The Midnight Eye Guide to Japanese Film”)

There are many stories connected to people's first encounter with Hideo Nakata's “Ring”. However, most of them have less to do with his film, but the remake released in 2002 and directed by Gore Verbinski. Sitting in the theater watching the first encounter with Samara, one which would soon spawn a tidal wave of Hollywood remakes of Japanese horror films, many, perhaps, thought how fresh and of course scary the films was. While highly stylized and polished, “The Ring” felt like a much-welcome departure from the meta-horror films following in the footsteps of Wes Craven's “Scream” (1996). However, many of us did not know at the time those ideas and image,s which felt so unique to us, came almost directly from the minds of Japanese directors who had been making movies like these for many years. But then again, how were we supposed to know? Names like Takashi Shimizu, Hideo Nakata and Kiyoshi Kurosawa were largely unknown, and their films would see their major release only after their American counterparts had made millions and excited audiences worldwide.

Now, 20 years later, the wave of J-horror had pretty much died down. Nakata, Shimizu and Kurosawa have for the large part of their careers stayed in their home country and branched out into other genres. However, there is no denying the kind of mark movies like “Ring”, “Pulse” and “Ju-On” left behind in modern-day horror cinema. You can clearly see “The Conjuring”, “Paranormal Activity” and “It Follows” being influenced, sometimes directly quoting these films, supporting the status of these directors within the genre.

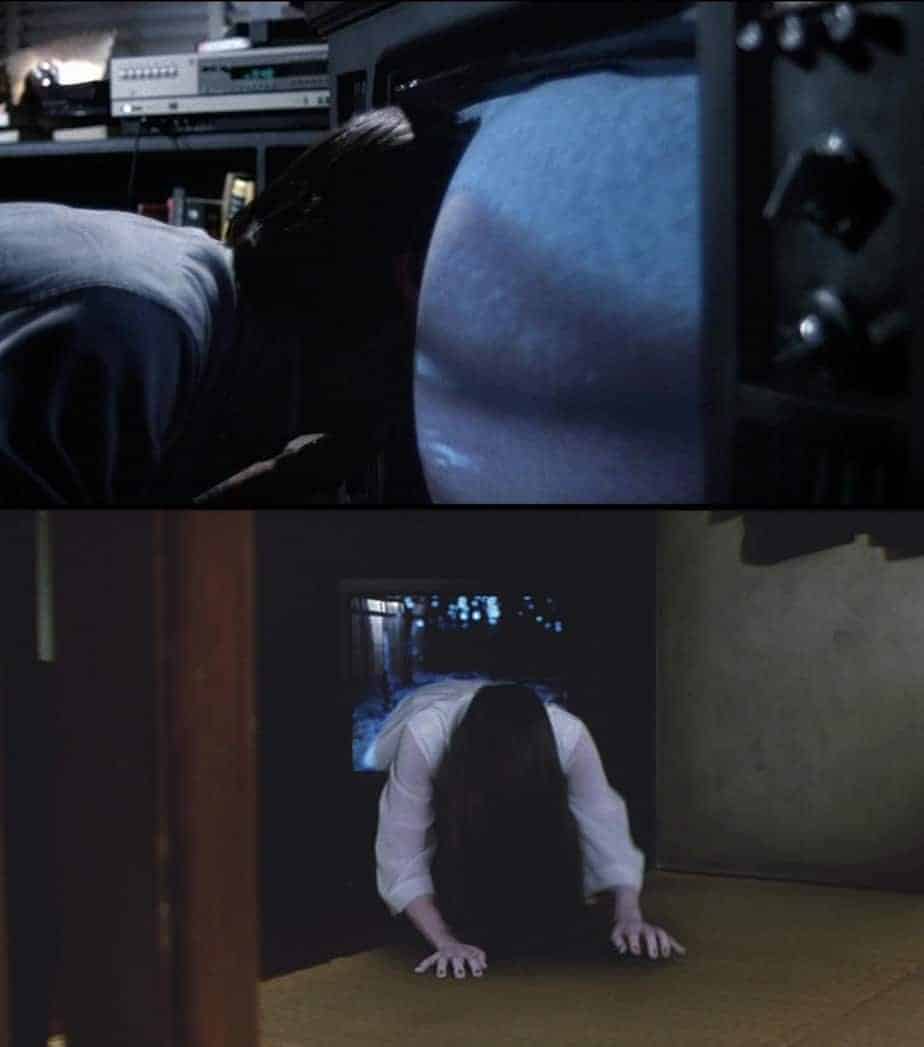

Nevertheless, it all started with a girl crawling out of a television set. As well as a weird, creepy VHS tape. And a phone call stating you will die in seven days.

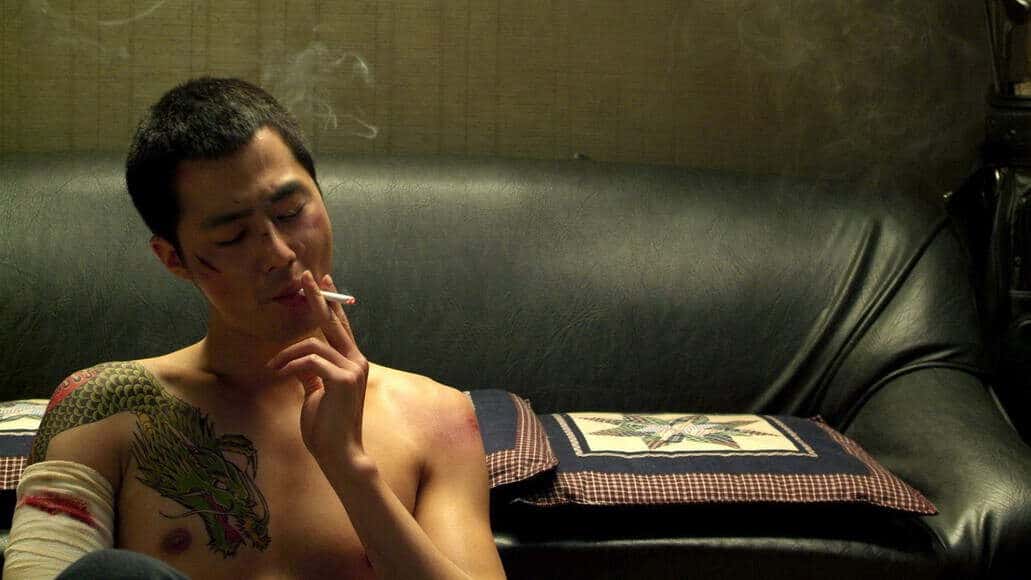

Before Hideo Nakata became one of the most important faces in the J-horror sub-genre, he started out as so many of his colleagues, making direct-to-video productions for one of the major film studios in his home country. Working for Nikkatsu, Nakata directed several entries of their “Roman Porno”-series, mostly cheap movies which demanded him to work on a tight schedule. Needless to say, the director has less than fond memories of these times, especially the amount of stress, as well as the quality of some of these movies.

In an interview from 1999 Nakata remembers his time at university and the films which ultimately inspired his approach to the medium. During and after his time at Nikkatsu many of his films already showed signs of the kind of director he would become. Perhaps the most important of these early films is “Don't Look Up” (1996), a movie which Jasper Sharp and Tom Mes describe as something of a precursor to the kind of themes later films like “Ring”, “Ring 2” and “Dark Water” would deal with. Nakata states the film was not very frightening to some, especially as it showed the complete face of the ghost character, a mistake he would not commit again as the finale of “Ring” shows. At the same time, the film dealt with a certain awareness of the medium, a connection between modern technology, Japanese folklore and a distinct sense of doom, all of which essential features for the “Ring”-films.

Buy This Title

In many ways, Nakata's “Ring” shows not only a director at an early high point of his talent, but also one of the rare cases of a film which goes far beyond its narrative foundation. Apart from its commercial success, “Ring” is a very unusual horror film, as it treats its subject without the use of sensationalist scares or effects (unlike its American remake). In the following text, we will take a look at this interesting film, its visuals and its themes, as well as how it still stands as one of the best horror film, if not one of the best films of the 1990s. Ultimately, “Ring” is a deeply disturbing portrayal of alienation, family and modern technology, one which presents evil as an unsettling force not just outside ourselves, but also within every one of us.

I. The Evil Within: the children in “Ring”

Even though the adults in the film play a major role, perhaps the most important parts in “Ring” (both versions) are the child characters, in this case Yoichi and Sadako. While the first is the son of Reiko, an investigative journalist trying to reveal the truth behind the story of the ominous VHS tape and the series of teenage murders, the latter is the “monster” of the film. Besides their connection to the tradition of children in horror films and their relevance, both also serve a much more significant purpose, highlighting the themes of neglect and isolation.

Considering her ambition as a reporter, Reiko (played by Nanako Matsushima) has trouble finding the right balance between being a mother to Yoichi (Rikiya Otaka) and her job. Countless times, communication with her son is done via the phone, for example, when she tells him she will not make it home on time and he has to make himself dinner. Although there is no debate, she loves her son – the scenes between the two speak for themselves – but there is a strong sense of disconnect between mother and son, evident in the numerous times Yoichi is shown isolated and from a distance. In one of the most obvious examples, he is on his way to school, looking up to his apartment, followed by a shot of his mother sitting in the darkness of their home watching the VHS tape once again. As if to underline the growing feeling of estrangement, the blinds of the apartment are shut.

Perhaps consequently, Yoichi has grown used to the situation looking for affection in other members of his family, making the recent death of his cousin Tomoko, due to Sadako's curse, all the more tragic.

One of the most interesting aspects of the character of Yoichi is his connection to Sadako. Although Hiroshi Takahashi's script is very vague and still leaves many questions unsolved by the ending, the fragments of Sadako's backstory become all the more relevant, especially with regards to her relationship to Yoichi, as well as her teenage victims in the beginning. Paraded around the country together with the mother, she has witnessed human cruelty first hand as well as neglect. In an attempt to defend her mother from a journalist's insults, she kills the man resulting in her being branded as evil and a witch. In the sequels to “Ring”, it is revealed Dr Ikuma (Daisuke Ban) had thrown her into a well where she spend her remaining days in darkness until she eventually died.

While the symbolism of the well will be further explained later on, it is one of the strongest metaphors for the kind of isolation in the film. Sadako has become a “sin of the past” Ikuma and others do not want to think of having accepted her role as an “evil spirit” and a curse, a self-fulfilling prophecy he has helped to become reality.

Since they both have experienced neglect and isolation, there should be no surprise Yoichi feels a distinct attraction to the evil spirit. Like Danny Torrance roaming the hallways of the Overlook in “The Shining” or Carol Anne communicating with the afterlife in “Poltergeist”, Yoichi can be seen multiple times looking for this specific connection. During the funeral of his cousin, he ventures into her room, seemingly in search for her memory, but also finding the place of her death. Later on, he can be found watching the cursed video on his own, after having searched for it in his mother's belongings. In fact, the very first image of him in the film sees him looking at the blank screen of a television, the source for much of the evil in the film, especially since it is the pathway for Sadako to enter the real world.

Visually, Nakata and cinematographer Junichiro Hayashi support the feeling of isolation and distance by framing the characters slightly off focus. Darkness or vertical structures further show the kind of estrangement, even at places these characters call home. Most importantly, Reiko and her son share the same kind of feeling, the way they enter the room of one of Sadako's victims is presented almost exactly the same. However, as each character lives in his or her individual sphere, isolated from the rest, there is no escape from that disconnect which explains the general lack of warmth and color in the film with only a few exceptions. One of the most telling examples is the first encounter of Yoichi and Ryuji (Hiroyuki Sanada), Reiko's ex-husband, with both characters facing each other in the rain and then departing without having said a word.

II. Water and Time in “Ring”: Transitory states toward the unknown

Considering the aforementioned cold evident in the depiction of relationships and the film's images, it perhaps should not come as a surprise to find water and rain as repeated visual features within “Ring”. Rain is the audiovisual companion in many scenes, such as the first meeting of Yoichi and his father, but also an inescapable reality for the inhabitants of Oshima island, the possible source of Sadako's origin. At last, it is also the part of Sadako's last resting place within the well, but also a decisive feature within her curse and the way she takes her victims.

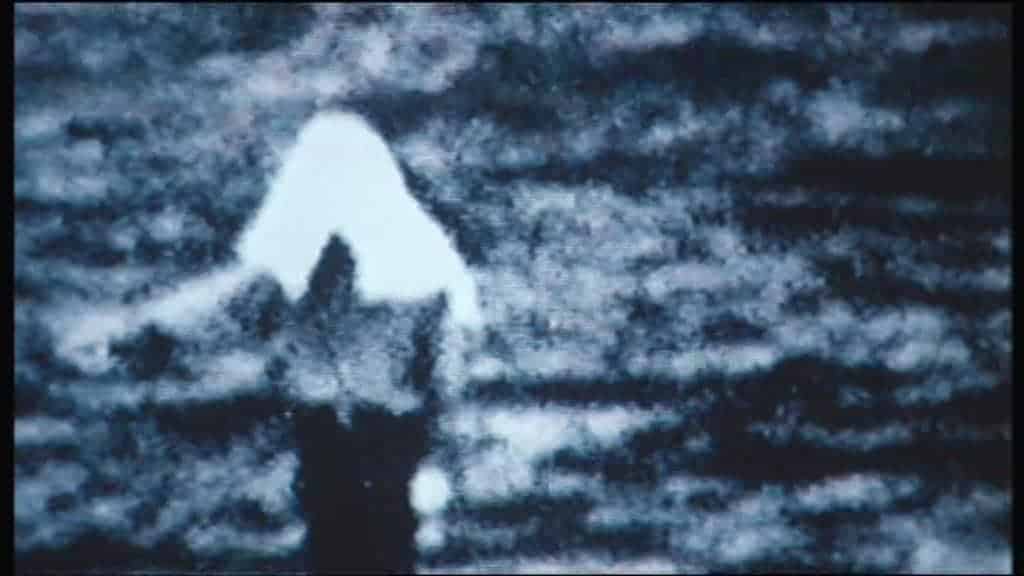

In general, the way elements like time and water are portrayed within the world of “Ring” can be seen in other J-horror features. Most significantly, Hideo Nakata's “Dark Water”, again based on a novel by Suzuki, depicts water as the core link between the hereafter and our reality. At the same time, it is also the bringer of death and decay, evident in the state of the apartment building in “Dark Water” or the state of Sadako's corpse at the end of “Ring”. Within a much wider framework, the works of Nakata, Shimizu and Kurosawa share a similar approach towards these elements by presenting them as agents of chaos and evil. In the case of “Ring”, blogger Jack Milburn refers to the transition of the image of the waves to the white noise of the television, an early foreshadowing of the fatal connection between these two themes. Author Carlos Aguilar considers this understanding of nature as part of Japanese folklore and culture typical. However, within the definition of the genre, there is another aspect regarding the kind of fear “Ring” (and also other J-horror features) want to evoke.

Essentially, many reviewers and authors agree upon one point when it comes to the first “Ring”-film: its lack of explanation. As mentioned before, many aspects of the story, parts of Sadako's origin, for example, or the nature of her psychic powers, cannot be explained if you only watch the first film. Interestingly, as the American remake attempts to fill some of these “holes in the plot”, it also takes away much of what makes the story as unsettling as it is in Nakata's hands. Most importantly, it is the concept of fear as an element equal to water, one raging within ourselves as well as being able to take over an outside structure, for example a VHS tape. Naturally, this has made “Ring” one of the most obvious targets for satire, like in the “Scary Movie”-series, but it is not uncommon within the tradition of horror.

Fear and evil are always close by, they are tides surrounding us, but the characters in “Ring” seem to search for its proximity, for instance, when Takashi (Yoichi Numata) spends hours on the beach looking out into the sea. The image is strongly reminiscent of Ellen Hutter (Greta Schröder) waiting for the arrival of the vampire in Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau's “Nosferatu”. Even though Takashi and Hutter fear what the appearance of the monster may bring, they also seem to sense (almost long) for evil to arrive. Of course, water or the ocean as the everlasting metaphor for a bridge to the metaphysical are the almost logical place to look for this kind of closeness. Additionally, these images and the sound of waves emphasize the kind of fatalist, many authors even say “apocalyptic”, tone of “Ring”.

One more feature closely linked to the depiction of water is the definition of time in “Ring”. Whether it is the period of one week before Sadako claims her next victim or the omnipresent countdown of the days left for Reiko to solve the mystery and rescue her family, the overall structure of “Ring”stresses the ideas of urgency and inevitability. Nevertheless, “Ring” is not a movie out for thrills or suspense, especially given its sometimes contemplative moments and overall eerily calm storytelling. For characters like Reiko or Ryuchi, time, past and present, remain features anchored within their physical world, decisive factors of life and death, whereas Sadako has reached a state beyond these limitations. In fact, she has also stepped over the boundaries of memories as she can literally reach from the realms of the past into the present and leave her mark.

Maybe Sadako's most terrifying feature is that her curse is not just about killing others, but actually erasing them from the world's memory. The faces of her victims bear her trademark, a violent grimace of fear distorting their features, much like the images of them on photography after they have watched the video. Since the world has abandoned her, as well as any memory of her and her mother, her transition to the physical world results in the distortion of time, of memory and of people the characters loved and liked. However, as the elements have taken over a different from in the modern, highly technological world, it is only natural modern media should serve as the “new” connector between the metaphysical and reality, between death and life.

III. The channel to our future: the cursed VHS tape

It seems only fitting an entity such as Sadako should transfer its curse onto a physical medium such as VHS and enter the physical world through a television. In the short-lived run of J-horror beginning in the 1990s with Nakata's film, many works contain a rather fatalist, or at least skeptical tone towards media from television to the internet. Most significantly, the works of Kiyoshi Kurosawa, especially “Pulse”, have developed from a rather obvious slasher rip-off like “The Guard from the Underground” to a combination of Japanese traditions and folklore doubts about technology and teenage culture. Both “Ring” and “Pulse” share this rather unsettling and ambivalent tone, given their endings which seem to suggest true evil has already escaped into the real world and will spread like a virus to each and every one. Interestingly, in the latest entries to the “Ring”-franchise, Sadako's curse, or rather the infamous video has been uploaded to the internet which stays true to the pessimistic tone of the original.

However, the physicality of the curse, the VHS tape, may have a deeper connotation than “mere” skepticism about media. Whereas many other movies of that area have aged rather badly in that area, the VHS-tape in “Ring” has not lost its eerie appeal, it has rather gained in that regard adding to the creepy nature of Sadako's curse and her crossing the borders of time and space. Much of this has obviously to do with the kind of images the actual tape shows, its use of grain and enigmatic, almost surrealist imagery. In combination with the story of Sadako – or at least the fragments of it given in the first movie – the visuals emphasize the link to Greek mythology, most significantly the legend of Cassandra and the image of the blind seer Tiresias. Also, with the specific tone of the ending, it cannot be regarded as a message from the past, but rather a prophetic message of a future which has come true the moment the first person sat in front of a TV set and watched the cursed VHS. According to Nakata, the television is a “passage to hell”, a tube, much like the well, towards absolute evil, hate and anger.

Many reviewers and authors have hinted at the obvious parallel between films like David Cronenberg's “Videodrome” and “Ring” with regards to their approach to modern media. While this reading might serve those considering “Ring” as a kind of meta-horror movie, there is a distinct difference here. If you take for example the most iconic images of both films, in this case Sadako crawling out of the television and James Woods' character inside it, Nakata's film eventually loses its emphasis on criticism and considers the set, much like water and the ocean, as a gateway. In terms of “Videodrome”, Cronenberg on the other hand, seems to be much more interested in the repercussions of television as a cultural phenomenon and how it influences ourselves, especially our bodies, resulting in a quite acidic comment on consumerist media culture. In “Ring”, physical media help distributing a message we cannot keep away from, and which will determine our time on earth predicting a possible future we are helpless to prevent, given the fact we only have one more week to live.

Conclusion

In 2018, Hideo Nakata's “Ring” celebrates the 20th anniversary of its release. Looking at today's horror cinema, its influence is undeniable and will likely continue for many years to come, but especially as modern technology keeps on expanding the horizons of our senses and knowledge. Its dark tone, its visuals and its take on nature as a force of evil define “Ring” as one of the most memorable entries in the short-lived J-horror era. Within the genre of horror it is a work of considerable skill and talent, one which has done for the VHS tape what Alfred Hitchcock's “Psycho' has done for the shower and Steven Spielberg's “Jaws” has done for sharks. But then again, just like the characters in “Ring”, we cannot give up our wish to be close to our fears, to our demise, afraid of and longing for the consequences of what might come. In the end, we only have seven days to find out before the sharp sound of strings and white noise determines our final fate.

Sources:

1) Totaro, Donato (1999) The “Ring” Master: Interview with Hideo Nakata

offscreen.com/view/hideo_nakata, last accessed on: 12/22/2018

2) Kermode, Mark (1997) Ring (review)

old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/review/481, last accessed on: 12/22/2018

3) Puddicombe, Stephen (2018) When videotapes were sinister – 20 years of J-horror classic Ring

www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/features/ringu-hideo-nakata-videotapes-lynch-haneke, last accessed on: 12/22/2018

4) Milburn, Jack (2018) Analysis of the Sound in Hideo Nakata's Ringu (1998)

jackmilburnblog.wordpress.com/2018/01/05/sound-in-hideo-nakatas-ringu-1998/, last accessed on: 12/22/2018

5) Aguilar, Carlos. Ringu

In: Vossen, Ursula (ed.) (2004) Filmgenres. Horrofilm. Stuttgart: Philip Reclam jun.

6) Mes. Tom; Sharp, Jasper (2005) The Midnight Eye Guide to New Japanese Film. Berkeley (California): Stone Bridge Press

7) White, Jerry (2007) The Films of Kiyoshi Kurosawa. Berkeley (California): Stone Bridge Press