Vanishing Time: A Boy Who Returned” is Um's second feature length film and his first to receive to a widespread release in South Korea. The film was ranked three for the box-office weekend when it premiered on 12 November 2016, behind “Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them” and “Dr Strange.” As at 9 July 2017, the film has taken approximately $3.5 million dollars in local box-office receipts.

Buy This Title

After the death of her mother, Sun-rin (Shin Eun-soo) and her step father Do-gyun (Kim Hee-won) – a demolition contractor – move to a remote island in order to start again. Sun-rin's relationship with Do-gyun is fractured as she blames him for the death of her mother. At school, Sun-rin is relegated to the margins until Sung-min (Lee Hyo-je) befriends her. It is this friendship between Sun-rin and Sung-min that proves to be pivotal to the plot. One day, Sung-min and his friends decide to visit a cave on the construction site, with Sun-ri tagging along. They discover a glittering egg which legend goes has the potential to stop time – possibly derived from the mythology of the Dalgyal Gwishin (Egg Ghost). An explosion takes place and seemingly Sun-rin is the only survivor.

However one day, an adult male appears and tells Sun-rin that he is in fact Sung-min and that he had been trapped in a timeless world along with his friends; only able to return when he became an adult. While Sun-rin is initially reluctant to believe that this stranger is her friend, she eventually becomes convinced that he is in fact Sung-min and tries to reintroduce him to his mother and the community. Not surprisingly, this does not go well, and Sun-rin's father and the Police believe that “Sung-min” is in fact a child murderer and paedophile and that Sun-rin has been deluded by him.

Working within the generic structures of the South Korean fairy tale film, “Vanishing Time: A Boy Who Returned” juxtaposes fantasy and reality, the world of the child with that of the adult, without privileging one over the other. Closest in sentiment and structure to Jo Sung-hee's 2012 “A Werewolf Boy”, the film is concerned with the passage of time on the bounds of friendship and childhood ties especially for those marginalised and othered by the community. Some online critics have interpreted the relationship between Sun-rin and Sung-min, as inherently problematic in relation to “Sung-min's” undecidable status: is he a child trapped in an adult body or an adult trapped in a child's body? To do this, we have to approach the film with adult eyes, rather than seeing the film from the vantage of Sun-rin as we are asked to do through the use of POV, close-ups and mirroring wide angled shots of Sun-rin and Sun-min sat together on the edge of the tree house.The use of such shots, and the frame, provides a mechanism through which the viewer is sutured into the text and through doing so, asked to see the events through the perspective of a child rather than of an adult.

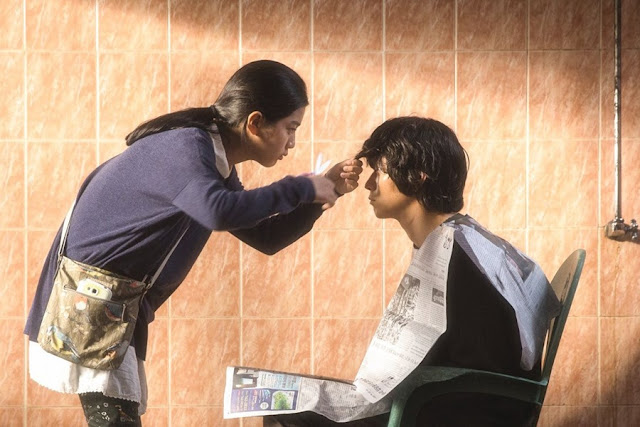

The shot above is a repetition of an earlier shot reproduced earlier in this review. Here, Sung-min wears the same type of clothing that he does in the first framed shot, while the dominant colour of Sun-ri's outfit is purple this time rather than white. This suggests that it is Sun-ri who is the more mature of the two: this is emphasised in scenes in which she teaches him to memorise events from the past that he has forgotten, and indeed, in one scene she cuts his hair just as a mother would.

The evident gap in age in such scenes is compensated by the emotional maturity or immaturity of the protagonists, which functions to cancel out such visual difference. At no stage in the narrative – and unlike “A Werewolf Boy” – is there anything sexual between the two, significantly so. While Sun-ri and Sung-min are soul mates, it is their friendship which structures the narrative and which embodies the innocence that is lost when we transition from childhood into adulthood. Shin Eun-soo's performance of Sun-ri is a dramatic tour-de-force, while Gang Don-woon is excellent as the frightened and emotionally stunted adult Sung-min.

The cinematography adds to the overall fairytale feel of the film and the scenes with Sung-min and his friends captured in a timeless bubble in which they can do anything they wish: the saturated canvas is juxtaposed by the drab world of reality. Such scenes can be interpreted as an example of what in Freudian psychoanalysis is called infantile omnipotence or magical thinking. Infantile omnipotence is when perceptual reality is ignored in order to fulfil repressed wishes.This is articulated through the dreamlike quality of the scenes in which the three boys enact out their childhood fantasies.

Overall, “Vanishing Time: A Boy Who Returned” is a magical experience that captures the fleeting innocence of childhood, which is contrasted with the harsh world of the adult in which freedom is an illusion. We are offered two interpretations for events in the film: our experience depends if we view the film through a child's eyes or through an adult's.