Nam Ron (alias of Shahili Bin Abdan) was born in 1969 in Kangar, Malaysia. He graduated from the Department of Theatre in the National Arts Academy in 1994, and has since worked in theatre, television and film as a director, writer and actor. His reputation was launched by the play MISI (co-written with Faisal Tehrani), followed by many successful stage performances. He has worked with most reknowned Malaysian filmmakers such as Dain Said, Yasmin Ahmad, James Lee, Tan Chui Mui, acting in main, supporting roles not mentioning many cameo appearances. His directorial debut, “Gedebe” was a loose adaptation of “Julius Caesar” set in the underground Malaysian music scene. In his film works Nam Ron skillfully combines genres cinema with sharp social commentary.

Though he made his acting debut on television in 2000, Bront Palarae, who is a Malaysian of Pakistani-Malay-Thai descent, first gained fame by portraying two characters in Cinta Tsunami, a television series in 2005. Since then, he started attracting a variety of roles in films including Anak Halal (2005), Man Laksa (2005) and Bilut (2005). Despite only played the lead roles 4 times through his career, he has won the Best Actor awards for all of them.

In 2010 Bront co-founded Otto Films and through the company, he co-produced, co-written & co-directed Kolumpo, a feature film released in 2013.

In 2012, Palarae joined the AQSA2Gaza11 Emergency Relief trip to Gaza organised by Aqsa Syarif, a Malaysian non-governmental organisation that focuses on helping the people of Palestine affected by the Gaza-Israel conflicts occurring that year. He was the goodwill ambassadors for the UNICEF's My Promise To Children campaign to emphasise children's rights in Malaysia.

In 2016, Palarae starred in a Malaysian sports football film Ola Bola,Chiu Keng Guan's latest film after the record-breaking The Journey. Not only that the film made RM15.85 million and became the 5th highest-grossing Malaysian film of all time, Bront also won the Kuala Lumpur Critics' Choice Award 2016, in the Best Supporting category, for his role in the film.

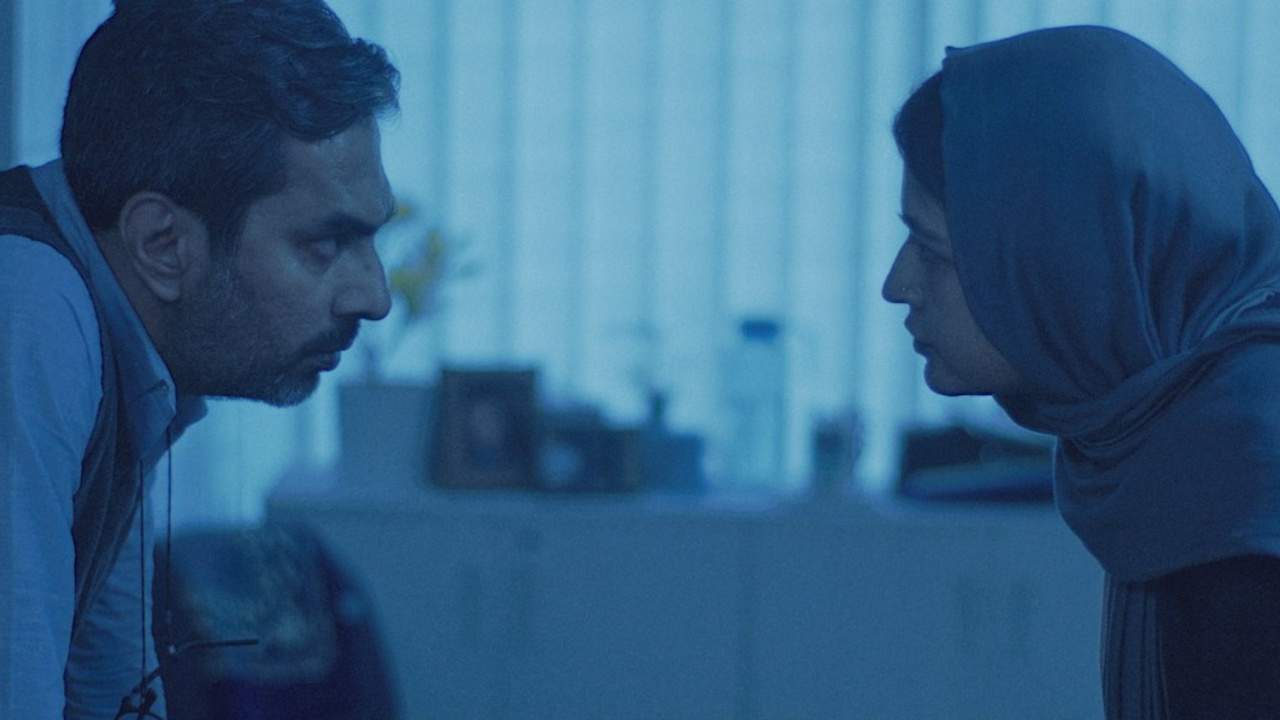

On the occasion of their film, “One Two Jaga”, screening at Five Flavours, we speak with them about their career, the hardships of shooting the film, police corruption and immigrants issues, Dain Said and Malaysian cinema, politics, and many other topics.

Apart from working in movies, you also cooperate with Unicef. Can you tell us a bit about that?

Bront: I am involved with the children's rights campaign, which focuses on giving children the right to education, the right to be children, in essence. Therefore, it is an anti-labour, anti-abuse, anti-bullying campaign. I think as an actor and director, I have an obligation to give back to society, even through small activities, and I found I could relate to giving rights to children.

How about your cooperation with Joko Anwar?

Joko loves UFO movies, and I was acting in this movie, “Nova” and he flew to Kuala Lumpur and after he watched the film, he tweeted about it. The whole team was excited to have Joko say something about the movie, and so the producer suggested having dinner with him. So, we went out and entertained him a bit, and a month later, maybe six weeks later, he contacted me and asked if I wanted to work with him in “Halfworlds”. I accepted, and this led to our cooperation on “Satan's Slaves”, and his latest film, “Gundala”, which we just wrapped a couple of weeks ago. For me, is kind of a dream come true, because I never expected to work with him. Because he is also famous in Malaysia, and I used to watch some of his early works like “Janji Joni” and I admired the stuff he did. It is a dream, but the more I work with him, It also gives me exposure to his brain and how he works, so it also helped me as a filmmaker.

And how was your experience in “Headshot”?

It was after “Halfworlds”, and Timo Tjahjanto came in the studio, since they could not fill up a role in the film, and their casting director was the same one working on “Halfworlds” and he recommended my name. So, I got a phone call and they send me some scenes and asked me to send back the casting reels. I did, and the next thing I know they flew me in and I shot my scenes in “Headshot”.

Can you tell me about your film, in the Kolumbo omnibus?

My piece was about immigrants and an Indian man who was offered a job as a graphic designer in Malaysia, but by the time he arrives he realizes there is no such company and he is saved by a restaurant owner. After he works for some time there, he realizes the real problem, because everyone who worked there actually had the same story. So it is a tragicomedy but I wanted it to be a city adventure. It is a recurring theme in my body of work, stories about immigrants, foreign workers in our country. Because I see them as potatoes, whatever green we see now in Kuala Lumpur is actually the hard work of them.

(Namron walks in)

So, Namron, we were talking with Bront about working with Dain Said. Can you share some stories about working with him?

Namron: I believe that Dain Said is brilliant. With his movies, he gives something not new, but definitely fresh to Malaysian cinema. How he structures the film, how he works with his actors. And personally, I like him very much, the way he works.

How about a personal story about him? (everybody laughs)

He is a guy filled with energy, he looks like he lives in his own world and we, the actors, try to go to his own world. Sometimes, working with him is… I cannot say funny, but it makes me laugh. He talks to himself, for example. He is a perfectionist. During “Bunohan” for example, the makeup artist was trying to make sweat to my face. So he wanted the drops to be large and the makeup artist tried to spray water in my face. So Dain came and said “No,no, no I do not want that. Let me show you.” and he takes the spray, and actually makes a big splash, a stain on my chest, not even my face. And then as he was leaving, he told the makeup artist, “you know how to do it, right?” (laughter). He is a fun guy.

And you have one, Bront?

Bront: During “Bunohan”, we did six weeks rehearsals and a workshop before we went to the set. I had a lot of talking scenes with Ilham, the eldest brother (Faizal Hussein), and we were waiting while they were setting up the cameras and the lights and Dain came and said (Bront speaks with Dain's voice): “Look guys, I want to rehearse the lines”, and we did a few lines and then he said, “all right, I don't want to over rehearse it. Yeah? All right.” Not five minutes have passed, and he comes again and says, I am sorry guys, I don't want to disturb you, but can we go through the lines again?” And we did, and then again he said, “it is ok guys, I don't want to over rehearse it”, and went to the other side of the set. And again in less in five minutes, he returns and says, “I am sorry guys, can't we rehearse it again?” And then we both told him, “it is ok Dain, we don't want to over-rehearse it” (everybody laugh). And he was like, “come on guys, don't be like that”, but he never returned after that.

We kind of have fun working with him in that way, because we observe him and he is a nice person to work with. I always call him a misunderstood genius, because some people find him very hard to work with, because he is a perfectionist and it is very hard to satisfy all his needs and standards in terms of execution. But we were lucky he liked working with us and we love working with him.

How did you come up with the idea for “One Two Jaga?”

Namron: I first wrote another script, with another producer, whose title was something like “Your Black Eyes Are Grey”. That project did not move forward because of budget issues, so me and Bront…

Bront: After the project was cancelled, two days later he came to my house and he was like, (imitating Namron's voice) “it is very hard to make a movie in this fucking country” (both laugh). And I was doing something else, my company was shooting some TV work, but I love him not only as a director, we have acted together and my wife produced his short film, he is someone we both hold dearly in our heart. So watching someone you have that much respect being in such an awful emotional status, I felt really bad. So, I had two days in terms of equipment, and at the time, we did not know what to do with it, how to utilize it, and at that moment, I thought, “fuck it, let's do something, I have two days left with the equipment and let's just have fun with it” and that was how it kickstarted. So he came back with a story and said he wanted to explore it. I knew that at the time he wanted to say something about the country, but I did not know what subject exactly and when he start talking about police corruption and immigrant workers, I thought, “that is dangerous but it is cool, let's try to develop it” and I thought that by doing that he would get distracted from the failure of his project and this was a good distraction.

Namron: I thought about police corruption and immigrant workers, because this issue had never been explored in Malaysian cinema. So, Bront wanted fresh content and I wanted to explore that issue, so we moved on. These issues in Malaysia are actually in front of your eyes; police corruption and immigrant workers is not something far away from you. So I interviewed immigrant workers and the story of “One Two Jaga” is actually based on a story one immigrant told me. For example, one case is about a woman from Indonesia who worked at my apartment as a landscape worker. One day I met her and she told me that she just came back from the apartment because her friend called her saying she was caught by two policemen because she did not have permit papers. So, the police asked money, like 500 ringgit, and because she did not have any, she called her friend asking to help her. So the police asked money from the woman I knew, and she had to go back and ask for money from other friends, and eventually she managed to release her from the police. So, the similar story in the film is actually based on this episode.

So, the police actually ask for money in such straightforward fashion?

Bront: It is always about putting people in a situation that they are in the wrong. So they do something wrong or they have the illusion of doing something wrong, and they want to get out of this, so the corruption is in the form of “I am helping you. You are wrong, I am helping you, give me some money and I will look the other way”. This is how they do it, it is not like “give me money now” it is more like, “you do not have a passport and I have to get you to the police station and probably in jail” and then the immigrants feel bad and ask the police to help them and that is how it happens.

How did you manage to overcome the censorship for the film?

Bront: The police was not happy, of course, about this, but from the start we were sure that we had two options: whether we do it outside Malaysia and work on the festival circuit, because I felt we had to say these things about our country to the world, because at the end of the day this issue made mostly sense in our country than to the world. So, we approached the police and had a discussion with them. We told them that we want to do it the right way, we don't mind taking some time, but if they do not allow us to do it, we are going to do it elsewhere. But we really hoped they would be ok with us. They were willing to hear us but it took us a month before we could set up some key points, like the real villain being the head of the police station.

After we finish, by the time we have set up everything after the edit, they did not like it. Of course, it was totally understandable. But then, we went to the censorship board and said, “the police couldn't do anything” because in the censorship board there is always a representative of the police. So I met with the chairman and we went over the key points, one by one, and the police representative would say, “this is not the proper proceeding” we had 18-20 scenes they did not want to show. So we went back and we told them, “you cannot forbid us to show these because it is not the standard proceedings, because if they were following the rules, they would not be bad cops, the reason they are bad cops is because they are not following the rules”. We were lucky because the censorship board was willing to play along, to give us a chance, to show it to society and to see the importance of the film. Because it had to be out there, because we were not judging the police, Namron did not say “all policemen are bad” but we were just showing what happens on the low level of the police force.

So, do you feel that the low-level police men are kind of forced to do that, due to their low wage? As in the character in the film, whose wife pressures him to get more money?

Namron: Yes, that is my theory, because they have very low paycheck. So everything nowadays is consumerism and they are human, they need more. Like other people, they need to buy a car, buy a house, mobile phones. And with a low salary, they cannot do that. But they have power. The low ranking policemen always say, “we do not have enough, our salary is very small”. Sometimes, they use this thing as an excuse to take money from other people. We have the example from Singapore where policemen have higher salary, so corruption is not an issue there. At least this is my theory.

What is the actual situation with immigrants in Malaysia now?

Bront: We have 5 million foreign workers now, almost 2 million of them are illegal, coming from Vietnam, Indonesia, Nepal, the Philippines, Bangladesh. The situation is as shown in the movie. Although they are part of the society, they are not perceived as such. The locals pretend they don't exist, despite the fact that they have been here for the past 30 years. Expectantly, some of them had children in Malaysia, and this has become another issue altogether, because those children are not really Malaysian, but are neither considered as citizens of their parents' country. We call them “stateless children.” So, whatever benefits we have as Malaysians, they don't get it, even in basic rights level, so the issue is what will become of those children when they grow up. Will they grow in the streets, without any education? Then their paths are either to become cheap laborers or join the gangsters and become a danger to the society.

So, Malaysia does not officially recognize these children, does not provide legal documents for them?

No, it does not, because their parents were never registered. In fact, the matter is never discussed, because the foreign workers issue is already big enough and this is like a headache on top of that headache.

Can you give us some details about the casting process of the film?

Namron: For Malaysian actors, I used my network, so I picked my friends and former associates, people I already knew very well. For the Indonesian and Filipino actors I used Bront's network, because he has worked in those places. I chose actors from those countries because I wanted the characters in the film to be realistic, I did not want Malaysian actors playing Indonesian or Filipino characters, because the sound is not right for me. And then you need a lot of time to process it, in order for people to believe that the character is actually Indonesian, for example. And Bront brought actors who were quite good, and working with them was very fun for me.

I was impressed by Amerul Affendi's acting, who seems to have the most demanding part in the film. Can you give me some details about your cooperation?

Namron: Amerul Affendi used to be my student in theater school. And along with Zahiril Adzim, the actor who plays the rookie cop, who was also my student, I used to pair them together on stage, as acting partners. Amerul Affendi has this very strong energy and that is why I cast him for the particular part.

Could you tell me a bit about your cooperation with cinematographer Mohd Helmi Yusof?

Namron: I knew Helmi Yusof's work, but I have never worked with him or even meet him before “One Two Jaga”. He is Bront's friend, since they studied in the same film school, and he was the one Bront suggested. My first choice was Yudi Datau, who was actually the DOP we had in the beginning, and I had worked with him in my previous film, “Beautiful Pain”, about autism. And I really liked his style of work, because of his process of working with the director. So I asked for him and he agreed and he came and we started talking about the film, about various details. At the time, the police had not yet approved the script, so we had to delay the shooting for some time, and we lost him, because he had another project. Then Bront asked Helmi, and we discussed for about a week. He is also a very good cinematographer because he is quick to catch what we want, the look and feel of it.

Bront: And the thing is Helmi has done more than 40 commercial films, but one of the art films he did was with James Lee, “Claypot Curry Killers”. He has been my friend for over 20 years, and when I saw that film I remember telling him that it was his best work. And he asked, “what happened to the other 39?” (laughter). When we lost Yudi Datau, I thought that we needed someone fast, someone flexible, someone to be able to adapt. Because Helmi has now started working as a director, so we started wondering if he would agree to cooperate, because I have heard that he did not want to do DOP work anymore. But finally he came on board, and we organized another round of location scouting and it was very intense for him to go through the prep for seven days, to try and capture settings in Kuala Lumpur that have never been captured before and trying to give us a certain perspective without calling for too much attention. Because, at the end of the day, it is not about the star, it is about the story and in the end we were so grateful that he came in, and the response we got was great. I am so happy for him too, because he got to explore some stuff he did not get to explore in other films.

Now that we talked about the locations the film was shot, can you give me some more details?

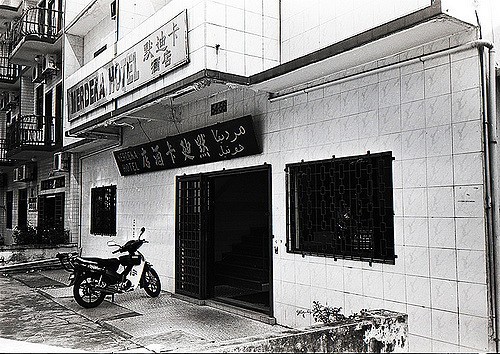

Namron: We aimed at showing locations that were never shown before, the back alleys, not the skyscrapers. We needed locations that would fit our story, like the back alleys and the hotel that features in the film. Because Bront said that we do not have enough budget, so we need to work with what we have. So we tried to find locations where we would not have to build the set. We found this hotel, Merdeka (means freedom). And we found it ironic, because the name of the hotel is Merdeka but the people living in are not Merdeka (laughter).

Bront: It is a cheap hotel. I remember being inspired by many films like “A Copy Of My Mind” and “Gomorrah” and we both like the Malaysian film, “Songlap” by Fariza Azlina and Effendee, and we were thinking of how to capture the essence of the films that we love, without coping them. And finally, we found a location that would give us that feeling. Because Malaysians always took those places for granted, they never actually looked at them. But once we showed them on the movie, things would never be the same with some of them, because people now look at back alleys like the ones presented in the film, and even though they are not the same, they remind them of the possibility of crime in those places, and the possibility of corruption with those people in those places. And in that fashion, the movie also brought attention, the right kind, to those issues, after it came out.

Namron: Some of them even came to the location we shot to take pictures, it became kind of a tourist attraction.

Bront: it is kind of stupid, in a funny way, because every back alley is like the ones we shot in, but people keep trying to find the particular one, behind the Merdeka hotel, and then cheering “I found the place”. (laughter)

Considering the themes of the film, were they any issues while you were shooting, with the police or immigrants?

Bront: No, we had police company most of the time, but we put them faraway, in the food truck.

Because you could not let them see what you were shooting, right? (laughter)

Bront: Yes. (laughter)

The only fault I found in the narrative is that it includes too many characters, that, unavoidably, remain unfulfilled. The material could easily reach 2 hours (the film lasts for 85 minutes) or even become a TV series. Why did that happen, was it a financial issue or something else?

Money was one issue, and we could not have all the cast for too much time, because we were lucky enough that all of them are big stars, but he problem with big stars is that they are always busy. But we would love to expand the story particularly on the Filipino “arc”, although in the end we couldn't. We were discussing, though, how the film was a collage of different stories rather than a biopic of certain characters. We also had some additional material, but it did not work thematically, because it took attention away from the central subjects. For example, we shot a lot of material regarding the corruption of the police department but then we decided to cut them out, because it would take attention from the other issues. It was a matter of balance and the fact is that the various issues are the central theme of the film and the characters are just part of the bigger picture. But you are right, because some people also told us that this should have been a series, because they would like to know more about the characters.

Can you tell me about your future projects?

Namron: I have just finished my next film. It tackles the issue of race, about the conflict between the Malay and the Chinese and it uses theater as the background, as the basic premise. It shows the fact that Malay are considered the supreme “caste” and the Chinese the minority in Malaysia, so it is a film about racism. The story is actually about a Chinese director who directs a Malay theater play, and the Malays do not like the fact. I tried to portray the theater as a nation and the director as a leader of the country.

We now have a new government, and more non-Malay people have gotten more politic power, they have been appointed as attorney generals, and our current Minister of Finance is Chinese. The situation is that the Malay businessmen and politicians do not agree with this, but for the majority of the rest of the Malay, like me and Bront, we do not mind, we have no issue with this. But these politicians and businessmen try to create conflict, because they have interest in holding on to their authority

So, among “common” people, there is no conflict?

Bront: You don't really see people as Chinese or Indians, once you have become friends with them. But on rhetorical, social and political level, these things have always been labeled or placed in a box and some politicians try to plant the seed of fear. Their rhetoric is like this: “Now with the new Malaysia, other minorities are getting the position to be authority, to have control and power. They are taking our future and they are taking our land, etc”. And after 60 years of plundering the resources of our nation (he refers to the Alliance Party and their successor the Barisan Nasional (National Front) coalition, that have been ruling Malaysia since 1973 and until 2018), obviously, it is not the minorities that stole from us, it was the majority of them that have been doing the stealing.

And you Bront, are you going to pursue a directing career?

Bront: I am making my own movie, right now I am at the stage of development, and it is a story of a take over, a corporate heist based on a true story, where one of our trust funds took over the oldest company in England back in 1980s. They managed to take over the company in 3 hours, which was a pivotal moment, because that company owned all the plantations, the mines, all the economic resources in Malaysia.

You are working non-stop, right?

Bront: Yes, I just finished “Gundala” and then I am doing a new movie with Nicholas Saputra from “Interchange” and we start shooting in Manila in December 2.

How is the situation with Malaysian cinema at the moment?

Bront: It is moving, but not in the right pace, I think. The government tries to boost it by giving grants, but there has been a lot of abuse of the money. I do not think we have enough material to push our boundaries. Dain Said only makes a film every five years, for example. We have 71 films per year, but I think only three are ok (laughs). So every year there are 3-5 films that are ok, the rest are replications of other films, mostly Hollywood films.

Do you think the recent change in government will help the industry?

Bront: We are one of the few countries is SE Asia that receive grants for films, Malaysia and Singapore actually, but you can see that other countries, like the Philippines, Thailand and Indonesia have come up with better works. The producers, the directors, the filmmakers, the film committee have been pushing new material and breaking new boundaries. I do not feel we are doing that enough, despite the help that we receive from the government.

You are set on dealing with political and social issues in your films. Why did you make this choice?

Namron: I always say that it is the artist's responsibility, my responsibility as an artist to bring these issues to my society. Theater and film is just a medium for me, I use them to speak about political and social issues. Not many Malaysian artists in film portray these issues, maybe due to censorship, because the producers are afraid they will lose their money if the film is not shown, although there are more in theater. So nobody wants to take this road, to take this responsibility, so I take it as mine for my society and my nation.