The first film by a woman after the fall of the Taliban regime, and Afghanistan's submission for the foreign-language Oscar, is an extremely pointy production that deals with the inconsistencies of the Afghan legal system, which lingers between Islamic, statutory and customary rules, as it presents the issues women face in the country, through a genuinely feminist view.

A Letter to the President screened at Vesoul International Film Festival of Asian cinema

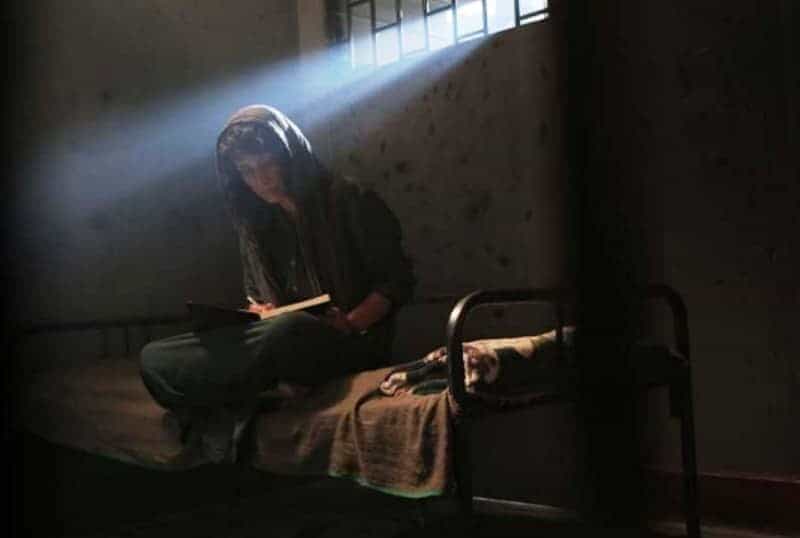

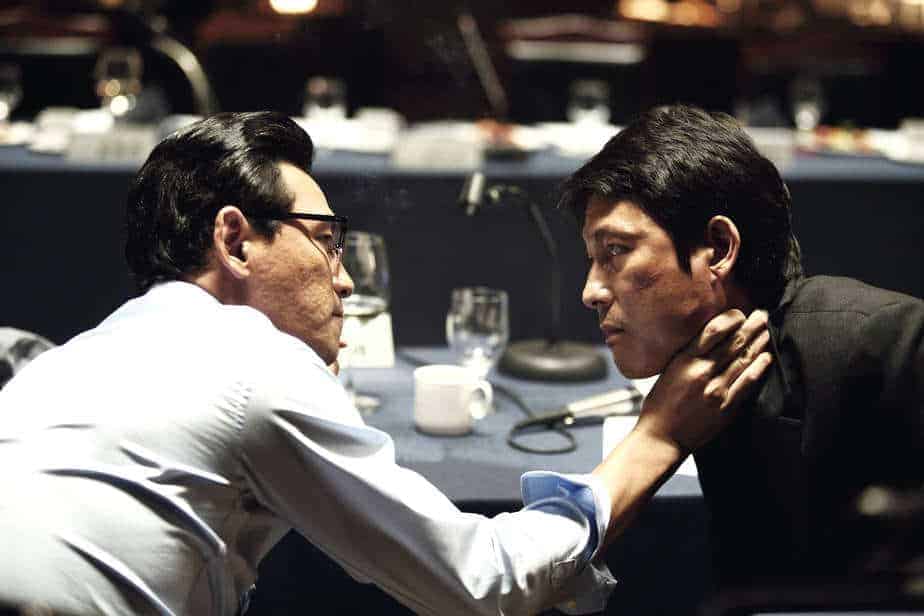

The film revolves around Soraya, a mother of two, who tries to balance her career as the head of the Kabul Crime Division and her life as the wife of a very rich but on the verge of alcoholism husband, who, additionally, is dominated by his gangster father. The already crumbling balance ends when Soraya decides to save a woman who is being accused of adultery and is actually sentenced to death by the village elders, and in the process defies the man in charge of the area, Commander Essmat Khan, who happens to be an associate of her father-in-law. The repercussions are huge and violence ensues in Soraya's house, in a series of events that lead to her killing her husband and her subsequent imprisonment, facing the capital punishment. The only thing that can save her is a letter to the President and the efforts of Behzad, an associate who is in love with her but manages to make things worse when he expresses his feelings through an exhibition of his paintings.

Roya Sadat in her debut feature film presents the awful truth about the living circumstances of women in the male-dominated, fundamentalist state of Afghanistan, making a point of showing that not even high-ranking officers can get away from the rules of the Sharia and the prejudice of society. As we watch her husband and father-in-law chastising her to the point of violence for working, and staying outside her house in “inappropriate” hours, and the fact that even the court takes into consideration that she was presumably drinking, regarding the final verdict, one has to wonder, how undeveloped Afghanistan is, at least regarding human rights.

As the movie takes a feminist view on the subject, we witness the blights of women in a country where 15-year-olds are being married to elderly men by matchmaking, where women are not supposed to have a career but to stay home and just be wives and mothers, in a world where men can do whatever they want with them without punishment and they get punished in the worse fashion, at the slightest “error”.

Soraya's whole life seems to be an act of resistance against the aforementioned status, with her attitude finding its apogee in a scene where she returns a slap of her husband even harder. However, Sadat is not disillusioned, and the consequences of these actions are portrayed thoroughly, starting with the aforementioned incident and ending with the film's finale. This last part also makes a point of showing that Afghanistan is still dominated by powers that can even ignore direct Presidential orders, in another pointy remark, political this time.

Although the whole story regarding the aforementioned is quite well presented, through Sadat's direction and Razi Kashi and Ahmad Faried Farahmand's editing, I felt that the secondary story regarding Behzad's unrequited love was unfulfilled and somewhat unnecessary in the whole concept.

Berouz Badrouj's cinematography, on the other hand, is excellent as it highlights all aspects of Kabul, both the life of the rich and the poor, and the events that occur in the deserts outside of the town. His approach to the action, which is mostly implied rather than depicted, seems to be a metaphor for the events that occur behind closed doors, which everybody seems to know, but none has the courage to speak about.

Leena Alam gives a great performance as Soraya, highlighting both her resolve in retaining her principles and not abandoning her career, and her despair on losing her children. Aziz Deldar as Behzad is quite good as the man in love who is willing to go to extremes to save the woman he loves, and Mahmoud Aryoubi makes a great “villain” as Karim.

If Roya Sadat wanted to make a film that will make its audience feel the injustice of being a woman in the country, then she has succeeded to the fullest, in a movie that highlights the truth of Afghanistan in a very accusing, but highly realistic way.