You don't need a tormenting rattling of machine guns to tell about terrors of war. You don't need buckets of blood to depict violence. Praveen Morchhale understands that perfectly. In his third feature, “Widow of Silence“, he gives a sour portrayal of internal unrests in Indian-administered Kashmir. With a subtle calmness of his previous works he brings into focus the fate of the most vulnerable and helpless victims of conflict zones around the world: woman and children.

“Widow of Silence“ is screening at the

International Film Festival Rotterdam 2019

Aasia (Shilpi Marwaha), a mother of a 11-year old girl living with her ailing mother-in-law, is a half-widow: “married, but without a husband.” Neither a wedded woman respected by the society, nor the one whose spouse has passed away. One night seven years back, her man was taken by the Indian army and nobody have seen hide nor hair of him since. Thus she shares the experiences of many women of the Valley whose husbands are gone. Most probably the government security forces are involved in those vanishings. The security forces who, allegedly, use anti-terror countermeasures as an excuse to keep violating the human rights in the region that has been torn by the years of territorial war between India and Pakistan. Thus thousands of men had disappeared, but are not declared dead, and the families have no way of finding out about their fate.

As “Guardian” article points out:

To file a missing persons report is not easy in Srinagar. Some families, while trying to report missing family members, have faced police pressure and intimidation after giving a report. Some have also had to move their plea to a different court just to register a first information report (fir). It is not uncommon for relatives to completely withdraw complaints due to fear.

The irony is that the government relief pension payment of 100,000 rupees ($2,253) per year is awarded only after families obtain a death certificate from district authorities. First, they must prove that the victim was never involved in any actions that might be interpreted as political militancy.

For Aasia, getting the her husband's death certificate is a struggle. Day after day she travels from a remote village to the provincial government office, where the ruthless clerk asks her same questions again and again, and sells her the same lies, trying to take advantage of the situation, both financially and sexually.

Aasia could remarry: Islamic scholars decided that women whose husbands gone missing can do so after four years of futile waiting (the much needed ruling came too late for many half-widows to start afresh).

Finding a way to deal with grief becomes even more important than the financial stability that would come from having her social status clarified. Yet, Aasia can't simply give up the hope against hope that her husband would come back one day, and that – along with the bureaucratic difficulties, keeps her from starting a new chapter of her life. Moreover, she seems to feel that giving up would mean allowing injustice to win.

Though her fight is hardly a fight, it has turned into a passive resistance. Despite her resilience, sorrow and mourning are always present in Aasia's eyes, and the situation affects others as well, wrecking her whole family. Schoolmates bully Aasia's daughter, and the girl is obsessively asking her grandma, “Was my father a good person?” but she can't get any reply as the old lady hasn't uttered a word since her son had disappeared. Even Aasia's bedtime stories for her little girl became very simple: “you'll get education and run away from this hell.”

The heroine's name seems to be a meaningful tribute: Aasia Jeelani was a courageous 30-year-old human rights defender, always standing in a front line to help the women of the Valley. She died with her fellow campaigners in a landmine explosion.

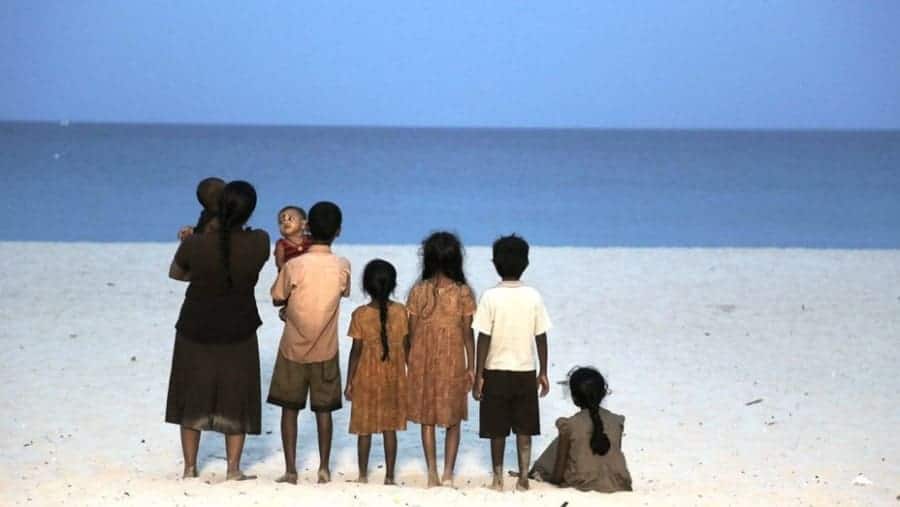

The director's way of telling stories is simple and minimalistic. Again, he teams up with the Iranian cinematographer Mohammad Reza Jahanpanah, who takes a point of view of a distant observer. Jahanpanah uses mostly wide angles accompanied by long and steady shots: his camera is often showing a scenery even after characters leave the frame. He grasps the overwhelming beauty of the Valley, but the used color palette creates a sense of hostility, coldness and roughness. He shows military checkpoints at the feet of the mountains (“Living in heaven and hell at the same time is very difficult,” comments one of the characters). There's only a little dialogue, and most of the cast (with a couple of exceptions, like the theatre veteran Shilpi Marwaha) are non-professional actors, recruited from amongst the locals, what gives a documentary-like feeling.

The film was shot on location in Kashmir's Dras region over the period of 17 days and Morchhale financed it from his own resources. He met Kashmiri half-widows while researching the script, thus he talks about existing burning issues with a strong and authentic voice. He also includes other stories. Those of people who had to leave their traditional occupation like farming to feed their families. Of people who are so used to gunshots that they stopped noticing them. However, although deeply immersed in reality, Morchale's movie also delivers (especially in stirring climax) some symbolic touches and kafkaesque parable. Whenever the driver of a worn-up jeep serving as a shared taxi appears on screen, sharing with his customers poetic deliberations, his scenes ring with a reflective and lyrical tone.

Some viewers might find it difficult to connect with the movie due to its lapidary structure, and some basic knowledge about the nature of the Kashmiri conflict is required. But Morchhale has undoubtedly brought up important issues and gave the voice to the people of the Valley, dwelling on their suffering and sorrows without a preachy tone and exaggerated melodrama. It is very rare for Indian filmmakers to take on the Kashmiri case in such an emphatic and problem-focused manner. While I write these words, “Uri”, the action flick being the typical military power muscle flexing, is topping the Indian box office. I regret that “Widow of Silence” is unlikely to hit Indian screens outside of the festival circuit (it has already been awarded in Kolkata in November 2018). Still for international audience, it is a rare opportunity to gain insight into problems that are not widely-publicized.