In 2018, Kidlat Tahimik (which means “quiet lightning” in Tagalog) was honored with the order of the National Artist of the Philippines in Film, the highest state's award for artists. Now his best-known work, “Perfumed Nightmare,” comes back to Berlin Festival, 42 years after receiving International Critics Award there. Upon its release, critics saw it as a breath of fresh air and it was considered a pioneering work of Filipino independent cinema. Some film historians associated it with the rebellious Third Cinema movement. Sincere yet conceptual in its formal jugglery, stunning with eccentric aesthetics, it was the distinctive manifesto of a budding director. With passing time, the film, proclaimed by Werner Herzog as one of the most original and poetic works of cinema made anywhere in the seventies, hasn't lost its rough charm and ability to mesmerize international audiences. Also, because of the heyday of the post-colonial discourse and growing awareness of colonialism's fateful hereditary, it may be even more apprehensible for today's viewers than it was for the audiences few decades ago.

Born in 1942 (when the Philippines were still under the American occupation) as Eric de Guia, in Baguio in the northern part of Philippines, the auteur graduated from Pennsylvania's Wharton Business School having earned an MBA degree and later moved to Paris to work as an economist at the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development. After five years he quit his job. He admitted in the interview for CNN Philippines: As I grew older, I thought (…) there are so many beautiful things in our culture but why doesn't it reflect in the way we behave, or the way we tell stories or the way we frame the world? There was something wrong in this unbalanced world. (…). I was so wanting to get out of that and become an artist. I had an inner wave, a tsunami, to express a story, and I don't want to do it the way I should've done it.

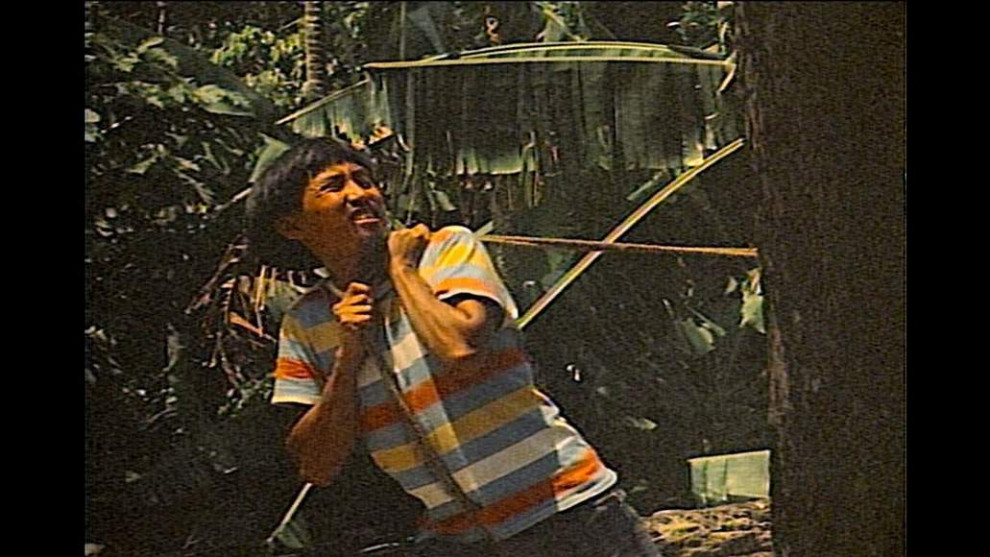

The Perfumed Nightmare screened at Berlin Film Festival

The future director went to Munich, where he mingled with the aspiring film community. Through its members, he met Werner Herzog and ended up playing a minor character in “The Mystery of Kaspar Hauser”. He also started to learn filmmaking – with a hands-on approach (It was like a child playing with his first toys, he later recalled). The“Perfumed Nightmare” was his creative testing ground.

In his memorable debut, Kidlat Tahimik drifted away from the established narrative conventions and combined a cinéma-vérité with fictionized sequences, a docudrama, semi-autobiographical elements, a fable, and a film essay. His movie can be childishly naive and bears an elder's wisdom at the same time. It is an imperfect or even ragged, and precisely structured. It seems a bizarre, yet fascinating hybrid, that connects different universes and aesthetics.

Drawing on his own experiences of “cultural underling of American culture,” he narrates the story of Kidlat Tahimik, a resident of a Filipino village allured by the charms of Western culture. Or I should rather say: he allows fictional Kidlat to tell that story by himself. The protagonist is a self-proclaimed president and founder of the rocket engineer's Werner Von Braun Fan Club. He grew up listening to Voice of America on the radio, admiring the imagined beauty contests' queens, and dreaming of becoming an astronaut. America and the whole Western world seem like a promised land to him. The land of limitless possibilities where he can gain significance while at his home village he may lead only a simple life suppressed by old customs and traditions. He lives in “a cocoon of Americanized dreams”.

We experience the world through Kidlat's eyes, with him, both an individual troubled with his nation's past and a hilarious rustic naif, being our guide. Obsessed with economic and technological progress, he explains the superiority of the Western science achievements compared with indigenous bamboo huts that “survive the typhoon,” constantly undervaluing the old ways. He idolizes Werner Von Braun, not aware of the scientist's Nazi past. It sourly mirrors the perceived “backwardness” of Filipino culture shadowed by the imposed Western society's superiority. And the latter is mocked when Kidlat repeats the famous words of Neil Armstrong. Distorted by his accent, the line sounds like “A small step for human, a huge leap for monkey”.

Kidlat provides the English voiceover, looks straight into the lens, explains the nature of things and his motivations, like a school kid would do when given a camera and task of keeping a diary. We constantly witness his inner stream of consciousness. There is something Chaplinesque in the character's innocence and guilelessness. Susan Sontag noticed this as she wrote: “Perfumed Nightmare” makes one forget months of dreary moviegoing, for it reminds one that invention, insolence, enchantment – even innocence – are still available on film.

Kidlat is a jitney driver riding a jeepney. The jeepneys are colorfully decorated vehicles used as a popular mean of public transport in the Philippines. Originally, US military jeeps abandoned after World War II, they were altered into passenger vehicles with roofs added as a protection from the sun. “Vehicles of war made into vehicles of life,” as Kidlat explains.

A symbol of transition between the past and the present, a part of a colonial past that reshaped the future, a passage between the worlds – in the “Perfumed Nightmare” they may be all of that. The “transition” and the “passage” are significant terms for the director. Kidlat is obsessed with bridges: firstly, those linking his village with the world. Secondly, the metaphorical bridges of progress like rockets joining the Earth with space, elevators, and escalators. He also crosses the bridges of his identity crisis, trying to figure out his place in a world where modernity clashes with tradition. There is a recurring line he says: “When the typhoon blows off its cocoon, the butterfly embraces the sun”. Kidlat would have to reinvent himself and to blow off the cocoon of “American dreams” – the perfumed nightmare. “To embrace to sun” – to understand that his strength comes from the native land and values.

Kidlat finally becomes disillusioned with the modernity. He goes to the West (where his grotesque job is refilling bubble gum vending machines), to find out the dark side of progress: lack of humanity, utter loneliness and soulless malls taking place of old merchants. There is no world that can be named “the first,” and Kidlat would need to construct a bridge of his own to find inner peace and to connect the conflicted elements that shape his identity. The personal experience of the director's journey from being a Western-educated economist, to avant-garde artist telling indigenous tales, added an authentic flavor to the movie. In the end, “Perfumed Nightmare”, as Piotr Florczyk accurately noted, through the use of allegory and symbolism, […] attempts to reassess the value of localism, indigeneity and native tradition in a world progressively dominated by capitalism. And what is also the movie's invaluable power, it provides the exceptional cinematic experience of changing the usual “Western” perspective.

Saw this film years ago when I first started getting into Asian films—I enjoyed the parts of the film where he talks about his village—-those were hte most interesting parts of the film for me.