Award winning film maker and Cultural Medallion recipient Eric Khoo who helms Zhao Wei Films has been credited for reviving the Singapore film industry and for putting Singapore onto the International film map in 1995. He was the first Singaporean to have his films invited to major film festivals such as Toronto, Busan, Berlin, Telluride, Venice and Cannes. Together with 12 Storeys' co-writer James Toh and actress Lucilla Teoh, he also wrote a White Paper which resulted in the formation of the Singapore Film Commission. Khoo was awarded the Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Letters, from the French Cultural Minister in 2008. Besides his filmmaking achievements, Khoo has produced several award winning films including 15 (2003) and Apprentice (2016).

Be With Me opened the Directors Fortnight in Cannes 2005 and My Magic his fourth feature was nominated for the Cannes Palme d'Or in 2008. Khoo has been profiled in Phaidon Books, Take 100 the future of Film – 100 New directors. The Pompidou Centre in Paris held an Eric Khoo film retrospective and he served as President of the Jury at The Locarno International Film Festival in 2010. The following year, he released his first animated feature, Tatsumi, which was invited to the 64th Cannes Film Festival and made it's North American premiere at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). In 2012 Khoo headed the juries at Asian Film Awards, Rotterdam International Film Festival and in 2013 the Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival. He was invited to be on the official Cannes, short film competition jury in 2017. In 2018, Eric was the show runner for Folklore a HBO Originals series Asia.

On the occasion of his film, “Ramen Shop“, screening at Festival International des Cinémas d'Asie de Vesoul, we speak with him about the path that led him to filmmaking, his contribution to Singaporean cinema, a number of his films and “Folklore”, Takumi Saitoh and many other topics

Additional questions by Jamie Cansdale

I read that your mother was the one that the “pushed” you towards movies. Is that true? In general, what was the path that led you to filmmaking?

Essentially, my mother was a cinephile and she loved horror movies. So, when I was a small boy, she would bring me and my sister to watch horror movies, virtually 2 or 3 a week. So, I grew up with a lot of horror films and also fantasy films. She liked action movies, James Bond, westerns and when I was 5 or 6 years old, she would always buy my drawing paper and pens and tried really hard to support me in my creative endeavors.

When I was about 8 years old, I discovered her Super 8 Canon camera, which she used to film us with as we were growing up. So I used that camera to film my Gi Joe action figure, I did something like stop motion, three frames, three frames and then these figures would come to life and my older friends, or my sister's friends would come over and watch and they were like, “How did you do it?”, and I felt like a magician.

So I carried on making those short films and then I went to study film in Sydney Australia, at the City Art Institute. I really did not learn much in terms of filmmaking, but my three years there enabled me to meet with filmmakers that shared my passion and also to see a lot of movies, even from video stores. Because at that time, in Singapore, there was a lot of censorship and there were a lot of movies that were banned and a lot of European films were not available. I managed to watch a lot of movies in Australia which benefitted me in terms of the scope of international filmmaking.

And then I went back to Singapore and had to go to the army, for two and a half years, which is compulsory. When I was in the army, I was still shooting short films. The Singapore International Film festival at the time, they created a short film competition section. So what I would do is submit my films to the competition. Sometimes my shorts would win, sometimes they wouldn't but I just kept submitting them. And in 1994, I did a short film named “Pain”, in black and white, 30 minutes long. With no dialogue. And I got a call from the festival and they said that your film was banned but the government will allow it to compete because the judges are foreigners. (laughs) . So the foreigners could watch the film and that year, in 1994, they came up with a new award. The short film competition started in 1991 and in 1994 they introduced the special achievement prize. So they gave me the Best Director and Special Achievement prize for “Pain” and the latter was actually a sponsorship from Kodak, from cameras to facilities to post production etc. So with that award, I made my first feature “Mee Pok Man”, which was, in essence, almost a sponsored film. And the film went to many festivals, like Berlin and Venice and it did really good in the box office in Singapore. So then investors came for my next film, 12 Storeys, which then went to Cannes, the first film from Singapore to achieve that. After that, I produced movies for Singaporean directors for about 6-7 years, because I wanted the industry to grow. And then I came back and did “Be With Me” , which was the opening film for the Director's Forthnight. So this is pretty much how it all started.

You have been shooting films since the 90's. How did the industry change through the decades and what was your contribution?

Actually, we had a very strong industry back in the 50s and through the 60s, because the Shaw Brothers were based there at the time, before they went to Hong Kong and shot all these martial arts movies. And they had Indian directors, Malay actors and scriptwriters and the Shaw were the producers, the ones who financed the projects. And these movies used to travel all over Asia and did very good business. But in the late 50's, Run Run Shaw left for Hong Kong. And then in 1965, Singapore gained its independence, so we split from Malaysia and some Malaysian directors went back to their country and the industry sort of died. There were not many films made after that, and also Hong Kong cinema penetrated the local industry, with the martial arts films etc. And for a long time, nothing happened in the local industry until “Mee Pok Man” came out, in 1995 and it sort of kickstarted the industry. I mean it was a lonely time for me with a handful of filmmakers but as the years went by, things got better, and nowadays we have around ten films per year, which is not bad for a country with a population of 5 million.

And what about the quality of those movies?

I would say the quality is good. If you look at Singapore filmmakers, they are more like auteur filmmakers, like Kirsten Tan, who won at Sundance for “Pop Aye”. Then you have another girl, Sandi Tan, who was also in Sundance with her film, “Shirkers”, and also won a prize for documentaries. We have Chris Yeo, who won in Locarno with “A Land Imagined”, and Boo Junfeng, who has done “Apprentice” and so, when you look at it, we have a lot of directors emerging from a very small population, getting into the ivy league film festivals. And for us, for my company, Zhao Wei Films, we try to nurture these artistic directors but we also try to cap the budget, make the budget not too big, so we can recoop. And the other thing is that the commercial films produced are addressed to Singapore and Malaysia and cannot travel beyond.

You also instituted the Singapore Film Commission.

Yes, I did back in 1997, right after 12 Storeys, with producer James Toh and artist Lucilla Teoh, which is really important because they have been putting money towards short films, and also helping filmmakers with grants for feature films. So it is very necessary.

Can you tell me a bit about “Tatsumi”? It rather stands out in your filmography.

When I was still in the army, while shooting short movies, I was offered to do a graphic novel by a company in Singapore called Times Publishing. They were forcing me to come up with a comic book for the book fair, which was six months ahead, but being in the army, I had no ideas, I was almost dry. And then a friend passed me a compilation of Yoshihiro Tatsumi's comics. And when I read that, it really inspired me and I was able to come up with an anthology of 12 stories within two weeks. It took me about a month to draw it out, so I made it in time for the book fair. And a lot of that I attribute to Tatsumi's works, they have given me so much inspiration.

So, even in the army when I was doing these shorts, some of them have taken something from Tatsumi literature, and through the years I have been following his work reading everything that is translated in English. Then, around 2010, I read his “A Drifting Life”, the manga of his biography and I realized I did not know anything about this man before, but now I know his life story, and I was very inspired to do a tribute to him, because he had inspired me all these years before.

I did not know how to get in touch with him, but I had a Japanese friend, who works at Fuji films, and he went down to track Tatsumi sensei and he was willing to meet me. So, many times, people ask me if I want to do animation, I do not want to do animation because I don't have a lot of patience, and animation takes a lot of time, but I felt that if I had to pay tribute to Tatsumi sensei, it had to be an animated work. But I had no idea how I was going to do it. So I met up with him in Jinbocho and we spoke for three hours, with a translator. And after the whole conversation, what I wanted to tell him was that I want to make a film that has his life story, but the biography he has written, carries on just until the 60's, so I needed him to do additional drawings, that would bring us to him meeting his wife, who is a pinnacle to his life. Then I would intercut his life story with some of our favorite short stories he has done. So, sensei and I sort of decided which stories would be included in the film. And then, after talking to him, he shakes my hand and says in English, “Make the film”.

I left very happy that he has given me the rights to make the movie, but I had no idea how I was going to put it together. So I met up with this guy named Phil Mitchell, who did a lot of animation in Canada and he was based in this animation studio in Indonesia, in a small island called Batam. It was like 45 minutes to get to the island from Singapore, and what he did was assemble a team of Indonesian animators who had just graduated from school. What I wanted to do is have a new look and a new style of animation, I didn't want to be anime or Pixar, but I also wanted to be exactly like sensei's style of drawing. Cause sometimes he would draw with a pen and sometimes with a brush, so the strokes were all very important to me. What they succeeded to do is “forge” his drawings, so their work was a combination of drawing and putting it in the computer and then they reanimated the whole thing.

And it was incredible, because when I got Tatsumi sensei to go visit the island, cause I also wanted to record his voice and all that, he was blown away by this young artists. He said: “This looks just like my drawing”. I said yes, they can now sell it and put your name on it. It was wonderful because he felt really happy. I remember when we got him to Cannes film festival, we were walking down the red carpet and he holds my hand told me he always wanted to be a filmmaker.

How old was he at the time?

He was in his late 70s. And later on, I discovered he loved cinema, particularly European cinema, but because he was somewhat of a recluse, he did not like to communicate and it is very difficult to be a director if you don't communicate. So he decided to stick to drawing. Even for a while, he was thinking of getting a team of artists to help him but he also could not do that, he did not like what they were doing to his artwork. So he continued being a pure artist, and did everything by himself and he would never conform, which makes him quite unique. So after the film premiered in Cannes and went to Annecy, the interest for his work was renewed and everybody would republish his work, like the Germans, which really good because some years later he passed away.

How did the idea for “Ramen Shop” came about?

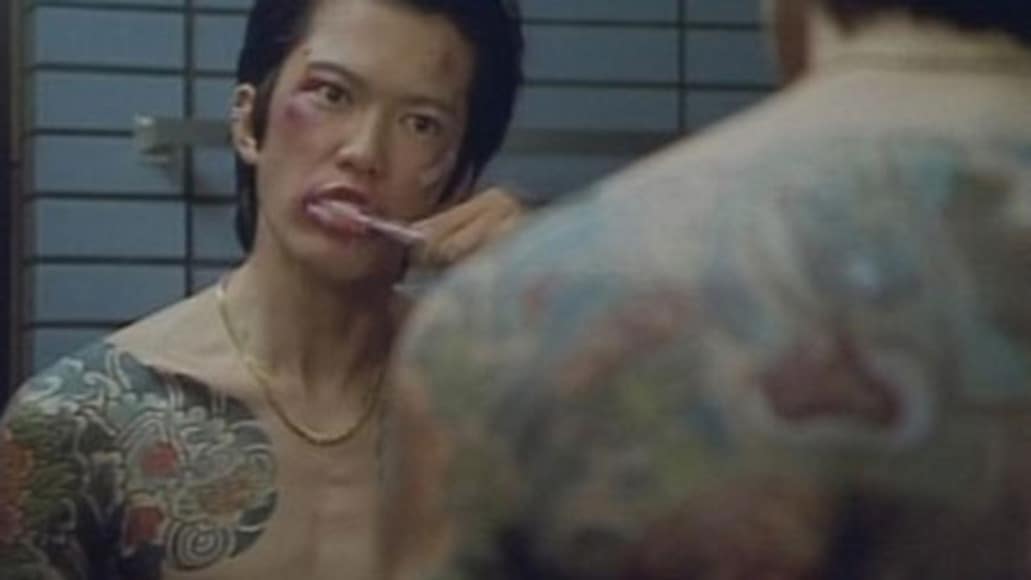

So, some years before this Japanese producer, Yutaka Tachibana approached me and told me that it was going to the 50 years anniversary of the friendship between Japan and Singapore, and if we could do a co-production of these two countries. So when he brought that to my attention, I basically have this big fondness for Japanese food and Japanese culture and I also love Singaporean food so I said to him, why don't we do a food movie? And that is how it started. It took us some time to decide what dish it was going to be, because I wanted it to be some kind of fusion. And I have a friend who runs this business that makes ramen noodles for Singapore restaurants, and a specific broth the bakuteh and also different densities of stock. So we got together, and we started cooking this thing and when we tried it, it was really good, and we decided to make a film about this particular dish. And also my main protagonist, Takumi Saitoh, in the film he is half Japanese, half Singaporean-Chinese so I wanted the whole hybrid to be about reconciliation and forgiveness.

The film looks a lot like a Japanese movie. Was that your purpose?

Yes, that was my purpose because me and my DP, Brian Gothong Tan we love Japanese aesthetics the feel of it and we shot in Japan and then we returned to Singapore, and it was not so nice (laughs). But it was meant to look as Japanese as possible.

So why do you feel these food movies are so popular?

You now, us Singaporeans are very greedy people, we love to eat, just like the French and the Japanese, it is all about food. And I feel, particularly in this movie, that food can heal, it has some soul in it, and I thought it would be very fit to be in a film about reconciliation and forgiveness.

There also seems to be a connection about food and memory in your film. Can you tell me a bit about that?

Yes, because when you taste something, everything comes back (snaps fingers). You know like that scene in Ratatouille and the horrible food critic. And when the film premiered in Berlin, last year, I was interviewed by several Western journalists, and some of the grown ones, they started to cry during the interview because they remembered their grandma's cooking or their mother's cooking, some food they have not seen for a while. Of course in the film, is not what they ate, it could be something else, a pudding, a pie, but the sentiment is universal, taste and memories.

Can you tell me a bit about how you guided the actors for their parts?

We wrote the script in English then it was translated into Japanese. But when you have a translation, a lot of the essence is missing. So the good thing is, what I did with my actors, especially Takumi Saitoh, is I told him: you know the character, you change the dialogue into what you feel the character would say. So, I workshoped with him during the rehearsals, and had an interpreter and then they would change the dialogue and rewrite it in English so I can understand it. The same with Seiko Matsuda and even his uncle, played by Mark Lee, who speaks this bad pinyin Chinglish when he spoke to Takumi, and they could not understand each other, it was like a duck and a chicken are talking. So we had to work with that and eventually they got it and they started hanging out together, going to parties etc. So the friendship eventually was there, and a lot of it happened during rehearsal improvisations. And finally, when we got to the location, we shot it like this (snaps fingers)

Did they know how to cook beforehand?

Actually, the bakuteh chef was there and he showed them how to do everything, so they learned it on the spot. And the good thing is that both Mark Lee and Takumi know how to cook. Actually, Takumi Saito's parents are cooks, they have a restaurant, and so he was always there watching them. In fact, when he travels, he always buys spices. So when he came to Singapore, I gave him some rare spices because I cook too during the weekends.

Can you tell me about your cooperation with the cinematographer, Brian Gothong Tan, particularly regarding how you shot the food?

He is a theater director and does a lot of installations, so his eye is really strong. And I told him the most important part of the film is during the end, when the grandmother and the grandson are cooking together, and there are almost no words. They communicate through cooking, it is like a spiritual connection. So what he did, is we found a kitchen with no ceiling, where the sun just comes through and he filmed around 4.35. By nature, he is very sensitive and has a very good eye. So we came up with all the dishes, in essence all my favorite dishes my mother used to cook for me, and we replicated those dishes.

Can you tell me how you came up with Folklore?

I have always been a fan of the original “Twilight Zone” and I love Asian ghost stories because they are terrifying, and scarier than most western films. And I spoke to HBO, they were interested in developing a series with me, and I said, why don't we do something about Asian horror? And we let each director from each county to decide what ghost he wants to talk about, and I emphasized to them that the language for the series cannot be in English, it has to be mother tongue, to give it the uniqueness of specific cultures. So HBO people were ready to let me choose my directors and to give them carte blanche in execution. So what we have now is a series where each episode is uniquely different from the other, which for us is a big victory. And having been invited in festivals like Sitges and Toronto, has done so much for the horror genre, which I love very much.

How did you come up with the specific directors?

Because I know them, and I like their work. With Pen-ek, for example, we talked at a festival and he told me that he wanted to do a horror film about a couch that eats people, a bit of a comedy. And I like Joko Anwar's movies also, so I thought this would be a nice selection of movie filmmakers. They were some Japanese directors (I won't say their names) who have done some horror films in their country, but HBO was not interested in them, they found them too mainstream. So I was really happy when I suggested Takumi Saitoh, and after I showed them his movie, “Blank 13”, they realized that he is a good director, and trusted him. In the future, I will be also developing something new with Takumi.

And what about the Korean director, Lee Sang-woo, he is not as famous as the rest of the directors.

He comes to Singapore for the International Film Fest so I have seen his films, and I like their rawness, their energy, and that is why I pulled him aboard.

Can you give me some more details about the Pontianak?

The legend also appears in Malaysia and the Philippines. In essence, she is a woman who is very seductive and kills men. And the legend is that when a woman is with baby and dies, he will come back as a Pontianak. An in order to prevent her, you have to put a nail in the back of the neck. And she only kills men. And she is known to be very seductive. And I have been talking with some people who have been doing research on the pontianak and supposedly, it predates the legend of the vampire. And supposedly Bram Stoker who created Dracula, read about the Pontianak before he did so.

The film also deals with immigrants and their situation in Singapore. Can you tell me a bit about their actual situation in the country?

It's terrible. There was a film about it called “Yellow Bird” actually, and Singapore has become so wealthy in the sense, that a lot of the labor that comes through, cheap labor that no one wants to do, the situation is getting better now. Essentially my episode, “Nobody” takes place in the 90's and back then the conditions for foreign workers were pathetic. They would literally live in rough shacks and there have been articles about laborers dying and then buried somewhere and nobody finds them, horror stories in essence. But since then, things have changed and now there are proper facilities where these workers live and they are somewhat protected.

And are these “illegal immigrants'?

No, no. What would happen is that companies would hire immigrants and give them work permits but treat them like dogs. Today though, the companies watch out, and ensure that there is proper protection, their situation is much better than it used to be and this is obviously good, because we talking about 500,000 people, domestic helpers, laborers, etc.

In the end of the film, the spoiled, bad boss is punished. Do you think he got what he deserved?

That part is also about domestic abuse. You know, there are actually domestic helpers who come from Indonesia and Sri Lanka, the Philippines and they live with families in Singapore and sometime you read in the newspaper they would take a hot iron and burn them.

Even now?

Even now, it is crazy. For me, it is unthinkable that people can be so horrible. And that for me makes it justified. If you are going to be an ass, you should be killed. And for me, I look at the Pontianak in my episode as something very pure, because she was raped by all these crazy guys and then she got pregnant and they killed her. And she was only a teenager. So, it is really about the underdog and to sympathize, that's what we wanted from this script.

Can you tell me a bit about Louis Wu? I thought he was great in the part of the horrible boss.

He started off doing a lot of variety shows, hosting, and now he is doing some TV work, but I have known him for ten years and I thought that, for this role, he's got the looks (laughs), if you wanted an asshole, no problem.

And how about Aric Hidir Amin? I also thought he was great.

Aric is brilliant. This movie, “Seven Letters” was done for Singapore's 50th birthday and included several directors. So, my segment in the film is about the Pontianak and the Singapore film industry set back in the 50's, where the Chinese were the producers. And a lot of our horror films had singing; you could actually see the ghosts singing. So I worked with Aric in that project, where he plays that joker sort of guy and I really liked him. So, when I was doing the script with Amanda Lee Koe, I thought of him and pulled him back on. He does a lot of TV and theatre.

And how did it occur that the episodes of Folklore have other directors playing some small parts? There is Joko Anwar and Boo Junfeng in yours, Dain Said in Ho Yuhang's etc.

I like them very much, that is why I included them. And Joko was happy to play the part and Boo Junfeng has this really smooth skin, so I thought it would look in this white outfit, like an angel.

Are there any new projects you are working on?

I have another series in development now, which I will announce in March, and then I am also working on my new feature, which will most likely be a coproduction with France and Japan. It deals with after life, but it is not a horror, it is more spiritual.

Do you prefer being a producer or a director?

The great thing about being a producer is that you can be in a helicopter, like watching your troops die from afar, but if you are a director, you are down there leading your troops. I think sometimes I like this script but I know I cannot do it justice so in these cases. I prefer to put people together, to assemble, and thus play the producer. Sometimes I enjoy being on the ground but occasionally, it is nice to have that aerial view.