–this review contains spoilers–

To this very day, I am able to recall the first time I laid my eyes upon “Onibaba”. It was a rainy Sunday afternoon, one of those Sundays where the comfort of your own home seemed too majestic to leave and all you want to do is laze around. I was in my bedroom, the air conditioner was on, and my back was rested against my bed. To complete the comfort, a snack was there for me to enjoy. It was heavenly.

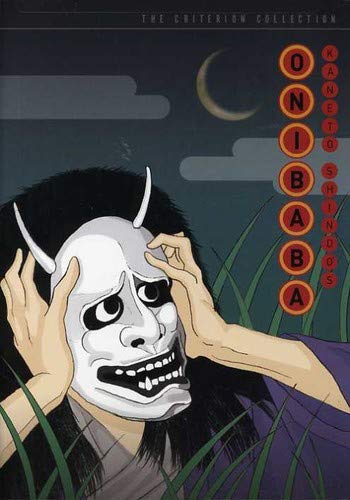

Buy This Title

In contrast, what took place on screen seemed to come out of the depths of horrific madness. We saw raging Susuki grasses all over the screen as the credits and the folk-like score, combination of jazz and taiko drums, played out. The camera showed a dark pit hidden amongst the grasses and then took us to its inside before climbing out, slowly. Our eyes were then directed to two wounded soldiers, dirty, afraid, and desperate, who were trying to escape through a towering Susuki Field by a river, only to meet a violent end in the hands of unseen attackers. We found out the two attackers were peasant women, one much older than the other, but just as handy with her metal spear. They stripped the soldiers of everything they deemed of value and then threw the corpses to the pit, where other corpses lie in wait. This is 14th century Japan, forever warring but never boring, and we just witnessed how two women, for the lack of better words, made their living.

We learnt that they were an old farmer and her daughter-in-law (they are never named, only referred to as Kichi's mother and Kichi's wife, but I chose to refer to them this way because I feel it is more appropriate). Their livelihood and security were demolished by the endless bloodshed created by the power-hungry rich. They lived in a small hut in the Susuki Field and were forced to turn to murder running, scared, and weakened soldiers to survive. Whatever valuables they took, they delivered to a sleazy underworld merchant who lived inside a cave with a perennially naked woman sleeping not far from him. The merchant agreed to trade the armors and weapons they stole for some foods. He offered them more if they were to bed him, but they were not interested.

The story continued with the return of their boorish next door neighbor, Hachi. We learnt that Hachi used to be best friends with the only man in their household, Kichi (the old woman's son, the young woman's husband), and that they were forced to serve under a military campaign by some big shot in some army. Losing the only man in their family turned out to be the original reason for the women's current activity. Over dinner, which Hachi invited himself in, the loud neighbor told the women how Kichi was killed when he and Hachi deserted the troops and tried to steal some food from a village. It was not long until Hachi joined the women's game with the soldiers.

The presence of a man in their lives disrupted the balance between the women. Hachi did not hide his attraction toward the daughter-in-law and we learnt that, for reasons which seem to have more to do with loneliness than genuine love, the attraction might not be one-sided. Their carnal trysts, the Susuki Field, their very lover's lane, are enough evidence. The older woman, fearing for her own survival if she were to be left alone by Hachi and her daughter-in-law, tried to offer herself to Hachi but was quickly brushed off. She then brought up hell over dinner with her daughter-in-law, underlining what kind of infernal punishment awaits people who make love outside of marriage, but again she was brushed off.

Her opportunity for a win came one night when a soldier wearing a demon mask invaded her residence and forced her to guide his way out of the Susuki Field. Using her knowledge of the surroundings, she tricked the soldier into falling down the pit to his death and later retrieved his demon mask. Donning the mask on nightly basis, plus a huge white robe and fake hair to make herself look otherworldly, the older woman scared her own daughter-in-law on her road to lovemaking session. What sort of ending does this leads to?

In case you have yet to realize, Onibaba portrays a nightmarish world, where concepts such as hope, mercy, redemption and freedom are not only foreign, but borderline non-existent. It would not be a stretch to state that the film may well be the bleakest depiction of any Jidaigeki-related product ever shot for the silver screen. Over the years, it has been read as karmic tale or a Buddhist parable or Hiroshima parable, and let me tell you that this is all valid. But I see the whole story as the manifestation of the Seven Deadly Sins:

– What Hachi and the daughter-in-law did is the product of Lust.

– What the mother-in-law felt towards them are Envy and Wrath.

– Sloth and Pride were displayed by the Merchant, who waited for people to bring him valuable goods but obviously did not consider them his equals.

– The people who had stakes at the war obviously illustrated Greed.

– And lastly, in an ironic turn of events, someone who embodied Gluttony ended up killing Hachi.

Since sins and hell are related, I guess it is safe to say this film is not only nightmarish, but also hellish. I have rarely seen films like this one, where the screen is bereft of kindness and warmth. Everywhere you look, it looks as if despair is captured and maybe even embodied by what is displayed on-screen. Only four or five other horror films, by my own count and preference anyway, could lay claim to this achievement. Nightmarish is a word to do the film justice. In the temple of J-Horror, I put Onibaba (1964) on top of everything else. If horror is the genre meant to unnerve us, then Onibaba (1964) is one of the very few films which fulfilled the expectations and the potentials the genre deserved.

And that is what makes this masterwork compelling to watch.

Kaneto Shindo, who died in 2012 at the age of 100, is known in the West mostly for directing “Yabu no Naka no Kuroneko” (1967), also a horror film but of a different breed from “Onibaba” (1964) because that one is closer to Kenji Mizoguchi (who was his mentor) while this one is closer to George A. Romero (at least in spirit). Another famous film of his is “The Naked Island” (1960), a dialogue-free portrayal of family in a remote island. In Japan, Shindo is a pioneer in independent filmmaking with the film company he founded, Kindai Eiga Kyokai, which released all three masterpieces I mentioned in this paragraph. And just like his mentor, he is fond of strong women.

It is most unfortunate that Shindo is rarely talked about as one of the best filmmakers Japan has to offer. A proclaimed communist, his films exposed the human condition like no one before or since could. Many believed being a native of Hiroshima, which was destroyed by the atomic bomb in 1945, led Shindo to possess what Shochiku Corporation reportedly called “a dark outlook of life”. He likes to pit his characters against the merciless nature of fate or even nature itself. Toward the characters he directed, he is simultaneously empathetic and unforgiving. He does not glance at them with warmth, but he refused to leave them in the cold. What he never does is judging. His films are also more raw compared to products of the same time-frame, nudity and violence usually abound. Speaking from a personal perspective, I see him as a precursor to Paul Verhoeven. Only without the sense of humor.

And just like many great directors, this film is his collaboration with his own stock crew. The older woman is played by Nobuko Otowa, his muse and lover. Like the great Italian actress Anna Magnani, Otowa is a dependable performer who looks like your every day people. You could stand next to her waiting for a train and not notice she once donned a demon mask for a horror classic. Her acting is very physical, and her sneers came straight out of pre-code Hollywood films. Her younger housemate is portrayed by Jitsuko Yoshimura, who won the Blue Ribbon Award in 1965 for her work in this film. Her talent is evident, whatever Shindo intended to express with her was delivered to the nines. She had also worked with Akira Kurosawa, Kinji Fukasaku, Osamu Tezuka, and Shohei Imamura. Yoshimura is the only one not belonging to Shindo's stock crew.

Another frequent collaborator, Hikaru Hayashi, scored the film. I would not want to spoil what the score sounds like to those who haven't seen Onibaba (1964), but I am certain you will never listen to taiko drums the same way ever again.

Lastly, Kiyomi Kuroda, a cinematographer who was fired from Toei for his political stance, met Shindo before the days of Kindai Eiga Kyokai, and shot many of his masterpieces. His work in this one is outstanding beyond any compliment, at the same time beautiful and gruesome. I am not going to say more of his mastery for my words could only fail to do it justice. Just know that whenever I see a frame of this film, I remind myself digital still has an unbelievably long way to go to equal film, let alone top it.

Before I end this review, remember when I described the situation I was in when I watched this great work of art for the first time as “comfort”? The same couldn't be said about what happened to the principal characters here. In another existence of irony, let me point out to the scene where the older woman reminded the younger woman against sinning in this world unless she wants to go to hell:

“What's purgatory?” The younger woman said as she drank a cup of water, “The dead are just ashes.”

She had a point. The dead may be ashes as far as she is concerned.

But whoever, or whatever, was chasing her at the end of the film, that's purgatory.

— This review is written by Omar Rasya Joenoes