Kazuhiro Soda's observational documentary filmmaking approach could leave each of his films like a comedian's self-imposed task to achieve a certain innocuous achievement, not knowing where it will take them. Following his self-imposed “Ten Commandments of Observational Filmmaking”, Soda gives himself no prior knowledge of his subjects – and so what may unfold – or script to film towards. He simply allows his own camera to role for as long as possible, allowing the story to evolve naturally.

Peace is available for streaming from MUBI

His 2010 work “Peace” is a documentary that very much follows this process, with minimal prompts from Soda himself along the way. The three key points of focus tell their own stories in their own words and work together to tell a narrative of some of society's unseen and forgotten.

The Kashiwagis are a couple who run a Welfare Transportation Service, taxing disabled and elderly clients around the city of Okayama. Toshio Kashiwagi takes a wheelchair user out for a day trip; a woman to work; and a “katawa” (deformed) shoe shopping. His work diary is a chaotic mess of scribbles.

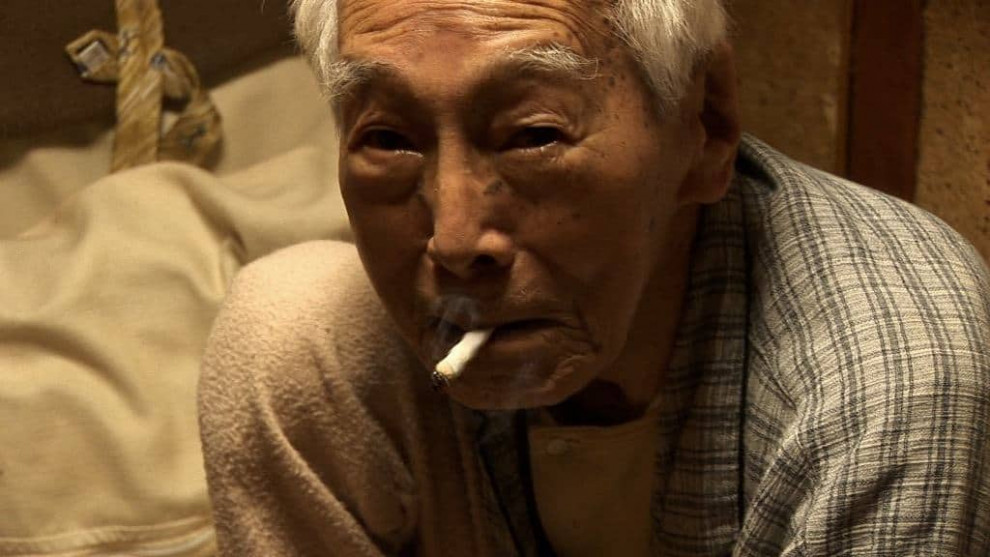

His wife, Hiroko, works their office, as well as providing care for elderly war veteran Shiro Hashimoto. Living in poor conditions in a tiny apartment hidden away in a side alley, she sprays herself with tick repellent before entering his home, riddled with mice as it is. Struggling with lung cancer, he still goes to karaoke, drinks and smokes his favoured Peace brand cigarettes, as these are the only pleasures he still has in life, as he laments the end of his days.

Toshio is also a caregiver himself: to a group of abandoned, lame and stray cats that happen about his garden. A now “official” clan of cats, he feeds them daily, observing the comings and goings of each as their number grows and decreases. Hiroko is not a fan of the additions to the garden of their modest home. And with the financial struggles their choice of career leaves them in, the question is as to why they continue to do what they do?

Accompanying the interviews with the carers and those the care for, Soda adds shots of those struggling to get themselves from A to B. Shots of people with walking sticks, wheelchairs, babies in prams, a blind person being led and a schoolboy weighed down by the numerous schoolbags he must carry, falling to the floor in tears.

Here we see a selection of misfits and society's forgotten – positions that they are well aware of themselves. A “katawa” (deformed) who asks “who would want to marry someone like me?” An elderly man, living on his own in a cramped apartment, when sitting alone he contemplates his death and who will take care of his funeral arrangements when he is gone. A “1.5 Sen man” (referencing the price of sending the postcard notifying of the draft call in the Second World War), he was not stationed in mainland Asia during the War, and as such, he is not someone that can be proud to have died as so many young men were taught to be. He experienced the shame of returning home. Not wanting to be a burden anymore, he muses that he should already be in Heaven.

As we draw to a conclusion, political discussion on the radio and politician posters are shown stating need for change. It is clear that more needs to be done for these people, but what more is needed is less obvious. The Kashiwagis outline the financial situation for those offering a service such as theirs, and it's a bleak picture. Teaching a class of transportation service workers in training, Toshio explains that with various government restrictions and taking into account the various costs involved, there is next to nothing left, if you are still left with anything at all. Formally a volunteer service, it put too much strain on those who did it, and so the government allowed people to charge, but the restrictions put in place have essentially kept it as voluntary work.

Both Toshio and Hiroko have accepted this situation and continue to do the work “out of habit.” So why? Hiroko and their neighbours view the cats that Toshio has taken under his wing as a nuisance, creating mess and attracting flies. Gradually, the older ones disappear as the group gets larger, with younger cats replacing their elders. Soda allows Toshio's words and their clear metaphor to speak for themselves. His observational style of filming would suggest apolitical filmmaking, with no wider research or additions from himself to add preconceptions or a political standpoint. Instead of pushing the message of the need to do more for society's hidden voices, Soda gives their voices a platform. This is less a social comment on the need for wider changes, more a portrait of people who have accepted their place and found a sense of peace in the world…as long as it comes with a box of matches.