“If you're too nice to pests they increase.”

In general, Tsutomu Tamura is mostly known for his fruitful collaborations with one of the greatest icons of the Japanese New Wave, director Nagisa Oshima. Starting with “Shiiku” (1961) most of Oshima's movies, such as “Boy” (1969) or “Death by Hanging” (1968), were based on the magnificent scripts by Tamura. The characters and their dialogues defined the right kind of mix between absurdist drama and bleakness which became a trademark for these films as well as the movement as a whole.

The Samurai Vagabonds is screening on Japan Society

Interestingly, Tamura is lesser known for his only film called “The Samurai Vagabonds”, a movie which brings together some of the future stars of his collaborations with Oshima. At the same time, it is a feature that sets the tone for the particular kind of writing he provided for these later works. Now that his film is re-discovered by institutions such as Japan Society, film enthusiasts are given the opportunity to see the only directorial effort of one of the most important writers of the Japanese New Wave.

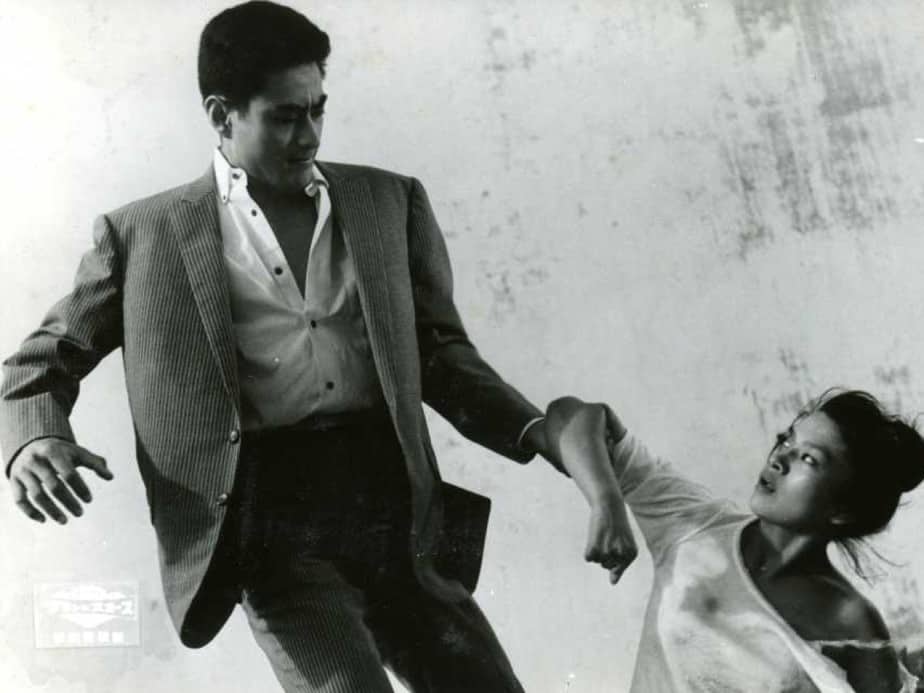

In a small mining town, a young woman named Hide (Kayoko Honoo) survives a suicide attempt while her lover dies. Blaming her for the death of his brother, Tatsuo (Masahiko Tsugawa) and his gang of thugs try their best to drive the woman out of town. Eventually, Hide's days become a routine of delivering leftovers to a local pig farmer to make some money, being bullied by children on the streets and occasionally beaten by Tatsuo's men. Although it has become almost unbearable, she remains unimpressed by any of these ordeals.

One day, a young man named Yasuo (Fumio Watanabe) comes into town to work in the local quarry. His physical weakness and his stuttering make him an easy target for the workers as well as Tatsuo's men who tease and bully him. As a proof of his manhood, he is forced to sleep with Hide, but the situation creates a connection between the two of them, revealing a dark secret and the reason Yasuo had to escape from where he came from originally.

Perhaps one of the most significant aspects of “The Samurai Vagabonds” is how it consequently avoids making any of the characters appear good or even likable. In that regard, its other English title “Volunteering for Villainy” is much more fitting since Hide, Tatsuo as well as Yasuo in the end, reveals deeply flawed and even despicable features of their characters. Notions of purity, innocence and community are thwarted with the loud crashing of rocks being destroyed in one of the machines in the quarry. Similar to the characters in Nagisa Oshima's film, and even the work of other New Wave directors like Suzuki or Imamura, survival is everything and, in the end, stronger than concepts of loyalty or love.

However, this does not mean the characters have no redeemable qualities. Hide's stubbornness, Yasuo's idea of “not getting caught” or Tatsuo's silent rebellion against his father's power and influence are complex, yet believable. At the same time, they have created a prison, or rather an inability to escape a desperate situation due to the kind of ties which keep them back.

Tamura's script along with the images of the film manifest the idea of a place defined by exploitation and hopelessness. While the old structures have locked themselves away behind their money, the others fight for bread crumbs and concepts of loyalty, honor and duty which have become somewhat abstract. Kiyoko (Masami Tsukioka) frequently confronts Tatsuo, her brother, with his own inconsistencies, his own weakness which is thinly veiled behind his sunglasses. Torn between duty towards his family and a certain affection for Hide, he has made a fool of himself, a walking contradiction.

“The Samurai Vagabonds” is a film about weakness as well as loneliness led by a strong cast and a great script by Tamura himself. While the idea of revolting against old structures was omnipresent, Tamura's film also expresses a distinct skepticism towards this concept which he sees as problematic in many ways. If indeed men and women remain divided by structures they simply cannot shake, if they cannot shake the dilemmas of the past, the notion of freedom is indeed flawed. “There is no use living in fear” as one of the character says, so running away and burning a few bridges might be the right way to start a life without being scared.