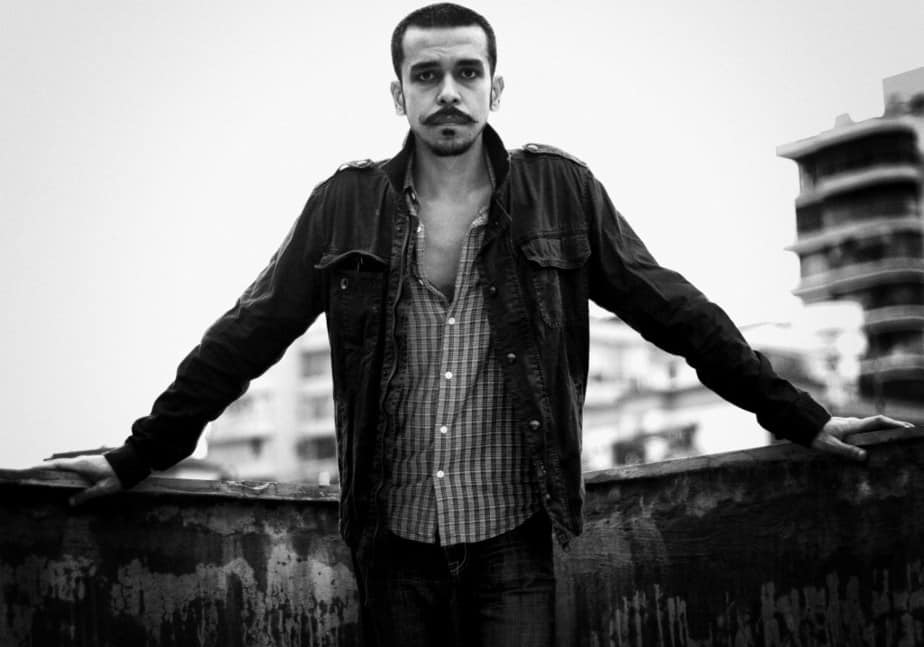

Devashish Makhija was born and raised in Kolkata, India. He studied at Don Bosco High School and pursued a degree in Economics at St. Xavier's College.

He began his career as an Assistant Director on Indian films, such as BLACK FRIDAY (2007). His first short films were awarded in India. His third short, ABSENT, had official selections in Toronto and New York Indian Film festivals while OONGA, his first feature, was a national success. AJJI is his second film.

On the occasion of “Ajji” screening at Indian Film Festival of Los Angeles, we speak with him in detail about the film, his career, his life, his perspective on various aspects of society, and many more topics

You have a degree in economics but you decided to become a filmmaker. How did that happen?

Why's your first question the most complicated one? ?

I'll trace this further back. My parents were born in Pakistan, came to India during the partition of India in 1947. I was born and raised in Calcutta. I won an under-12 national championship in karate. I almost got killed in a riot on the 6th of December 1992. I sang in a rock band for a few years. I danced in a contemporary troupe for a few years too. I failed chemistry in 8th grade. I cracked a 100/100 in mathematics in the ICSE in 10th grade. I was a trivia junkie, Quizzed like a beast. I first failed a couple of my papers in first year B.Sc. Economics. Then cracked a first class by the third year. When I left college I became a journalist. Then a copywriter cum art director in advertising. Then I reached some sort of a point of no return with my non-stop confusion, got into an unreserved compartment in a train bound for Bombay. And proceeded to make my past redundant. So the journey from economics to filmmaking had behind it almost two decades of unadulterated confusion.

On a serious note though, the choices we make at every step are decided cumulatively by our circumstances, our personalities, our influences and our ambitions, ALL of which keep changing through our lives.

I was a reluctant student of economics in college. I studied it simply because I didn't know what else to do. Also, we weren't made to think about Welfare Economics in the contemporary world, or made to ask questions of the current state of our economy. Perhaps what put me on this road to questioning the status quo through my stories was the fact that I felt much aversion to studying economics the way it was taught.

In fact, I've been perplexed by our education system all the way back to 5th grade, when in history too we were told to accept such simplistic truths about our ‘leaders' and our past that I always doubted what our elders and teachers claimed was the ‘truth'.

As the years passed, I started to understand that this ‘truth' is so complex that it cannot be processed by a juvenile mind. Hence our earlier years become an endless series of learning, then unlearning, then learning the same thing again with fewer presumptions and then unlearning it yet again when new complexities present themselves. Some of these questions found their way into two children's books – ‘Why Paploo was perplexed' and ‘When Ali became Bajrangbali' – the first questions the things we make little kids presume, while the second questions the ‘gray areas' of development, and even religion, while we're at it.

Now for the last few years I've been doing this through my films.

You are also an author, can you tell us about this capacity?

Writing defines my being. I don't limit my stories to any medium. If a story cannot become a film I turn it into prose. If a piece of prose cannot become a children's book or a novel I turn it into a short story. If an idea cannot become a story I write it as a poem. There is a lot of cross-pollination of my ideas and stories between mediums. I enjoy telling stories. The medium is secondary. Both as an author and a filmmaker I'm essentially telling a story. The craft of the medium is entirely at the service of the story being told.

After my first book of graphic-poetry (‘Occupying silence') and the aforementioned children's books, Harper-Collins published a collection of 49 of my short stories, ‘Forgetting'. Almost half the stories in this book were first intended as films. For a few years in between, any idea or story that the world refused to have as a film, I would write down as a short story.

This cross-pollination has led to interesting shifts in my work. My prose and poetry have become more visual over the last decade. And my film writing has found an economy of phrase and expression, the kind that poetry and short story writing demand.

My second book of poetry ‘Disengaged' and my first young adult novel are both out later this year.

Can you tell us a bit about your cooperation with Anurag Kashyap and Shaad Ali?

‘Black Friday' allowed me the opportunity to ‘research' like no academic procedure ever teaches you. Anurag dropped some 10 kilograms of documents before me, and asked me to ‘research' this story and draw up an exhaustive timeline of events / people / places, from which we drew up a structure, and he proceeded to weave a screenplay. I figured out this marathon task as I went along, lying and conniving my way through to people and places and archives which otherwise would never have been accessible. What this taught me was the narrative merit of truth. I found that a compelling fictional ‘story' finds many many more takers in the audience than even the most interesting piece of documentation of fact. I think the seeds of my current preoccupation were sown then. I decided to tell stories that would find their resonance & material in ‘fact', but would by themselves be ‘fiction', so that I could ‘engage' the viewer / reader even while holding up a mirror to our twisted, greedy, insatiable selves. As a result, more than anything, ‘research' finds an important place in everything I do.

‘Bunty aur Babli', on the other hand, was my film-production school. Everything about the mechanics of making a film in Bombay I learnt in that one crazy year as a chief Assistant Director. This film had three of Bombay cinema's biggest stars at that time. And YRF was making a film the kind of which they had never made before – on real, uncontrolled, chaotic locations. We shot in practically every city and town in U.P. Despite a shoot unit as massive as ours, we shot at breakneck speed through Delhi, Agra, Benares, Lucknow, Kanpur, Dehradun, Mussoorie, Rishikesh, Hardwar, Chunar, Chopan, Dhaulpur, on trains, bikes, in buses, cars, planes, on foot; whatever Bunty and Babli would do in the frame, the rest of us had to do outside of it too. The film was a riot of images, of colours, textures and light. And it was left to me to bring streamlined order to this unhindered chaos.

After this, I spent a year researching and writing the script of ‘Bhoomi' (Homeland) in which I explored the fractured idea that is ‘India' through the Kashmir terrorism, Assam insurgency (ULFA) and Maoism situations, told through the story of three young students in Delhi University who also find themselves tortured with questions, but never find any answers. This was directed by Abhik Mukherjee (the cinematographer of ‘Bunty aur Babli'), but never released.

What inspired you to shoot “Ajji”?

There is ‘reservation' in my cinema. My cinema is almost entirely reserved for the voiceless – those who have little or no representation in the mainstream – neither in storytelling, news, nor the daily discourse. Everyone not getting the same share of public resources, access to justice, and basic human rights, makes me angry. Some people have such easy access to their Rights and the machinery of Justice, whereas others go through their lives being crushed by constant brutal reminders of how inconsequential they are, and how they will never ever receive even the bare minimum that is rightfully theirs. The anger I have felt on behalf of the wronged Adivasi (tribal), the unfairly treated minority, the subjugated lower class, the reviled worker class, I put all that into “Ajji”. Her fight for gender justice is more universal in appeal than all the others I've mentioned earlier. And so it allowed me to express my ravenous rage unhindered.

“Ajji” was a response to what we're seeing and hearing more and more in the world around us. Men make the rules in this world. Perhaps always have. We've reached a point where religion, politics, business, sport, entertainment, every sphere is ruled by men. Men are celebrated for their success more than women are. Women are seen as silent supporters, clapping from the wings. It might be 2018, but apart from the odd token celebration of the female energy, strength and spirit, women are still largely not consulted in active decision making. This has made men disregard a woman's will. If she says ‘no' it is not taken seriously enough. If she demands equal status, she is reminded again and again of the tenets of class, religion and society – all of which were made and set in stone by men. And if she challenges this male authority, the woman is often ‘shown her place' – not least of all, by being subject to Rape.

In general, where do you draw inspiration from?

My starting points are often anger, unrest, agitation. This manifests either in a character, a setting or a story idea. And I take it from there. Throughout the journey, I keep reminding myself of that initial emotion I felt that made me embark on the narrative journey. If its Anger, then I remind myself of that anger I felt at every step, so I don't lose sight of it. It helps keep the end product streamlined.

One of the film's posters seems to imply some connection with Red Riding Hood. Is there actually one?

Yes. Red Riding Hood, underneath the surface, is a treatise on paedophilia.

In all the adaptations of Little Red Riding Hood across countries and cultures, there's always a Huntsman or a Woodsman who comes to kill the wolf. In some adaptations, the little girl herself turns vigilante. But in none of them has the old grandmother been explored. We wanted to see how the most helpless, least likely candidate in a family at the bottom of the social pyramid would go about navigating a task as difficult as this. So we made the fable some sort of a subtextual fabric to this film. We just replaced the literal jungle with a metaphoric one – of ‘construction' – the root evil of our times – the disastrous ‘development' that poses our planet with, arguably, its biggest threat.

Why did you decide to have an elderly woman as your protagonist? And why did you choose Sushama Deshpande for the part? How did you guide her very difficult role and how did she respond in the ending scene and the ones where she has to cut meat?

When a woman such as Ajji is consumed by her fury at over half a century of relentless injustice, she would get completely obsessed by what is driving her. To a woman like her nothing else of her life as she knows it would hold her attention any more. I wanted to explore an obsessive, fearless protagonist, yet one who is the least likely candidate for the kind of extremes Ajji has to inhabit.

As writers of film, first we form our ‘intent', then we write that character sketch, and then we start navigating the story. And as the story grows and morphs and expands, the character starts to change. Character affects story. And story affects character.

Ajji was initially a warm, gentle granny not inclined to violence. She was meant to transform radically over the story.

And then we met Sushama Deshpande. In her eyes, there was a fire already. One lit decades ago. I jumped at the chance to use it. We changed the character into one already in turmoil. The new Ajji we fleshed out afresh had spent decades questioning her status in a patriarchal society and family. She had been restless, and never known what to do about it. And bang, now, in the twilight of her life, she got the opportunity. She got pushed too far into a corner. And the fire exploded into an inferno.

Although Ajji was driven down this path by the grandmother within her, by the time she's reached this point of cold-blooded intent, she is no longer the grandmother we saw in the beginning. This reaches its heartbreaking culmination in the last scene – where she's lost the grandchild who she did all this for. Manda – more than anyone else – recognizes this, and grieves the Granny she has lost. Her parents have now finally taken the place of her Granny. Ajji will never have her grandchild's love all to herself again. To make Ajji shed her femininity to some extent in the climax (she looks almost like a transgender as the prostitute) was to foreshadow the death of the ‘mother' within her.

And that is the biggest irony perhaps of this story – the very instinct that drove Ajji to avenge her child, is the instinct she is required to sacrifice to complete the task.

Sushama epitomized all the complex traits I needed for this character. There is a deep comfort she exhibits with her sexuality. Yet, there is something curiously androgynous about her. I needed Ajji to be able to convince Dhavle as a prostitute, or else the sharp wolf that he is, he would've caught her out. To make her convincing for Dhavle, she had to be convincing for the viewer. Sushama brought the amalgamation of all those qualities. Some god of cinema up there brought her to “Ajji” when we most needed it. Nothing logical can explain it.

Sushama Deshpande brought to ‘Ajji' a depth of politic, of empathy, and feminism that I did not – and can never – possess.

She's a vegetarian. Most other actors had balked at the idea of cutting meat, expecting me to ‘cheat' it with the camera. But she didn't bat an eyelid. Once she had said ‘yes' to the film, she was prepared to do anything and everything we threw at her. She chopped meat in the workshops we did, with a devout diligence. When asked if she was ok, she would say that we'll speak about all this once the film's over. Until then she has a job to do, and would rather not discuss it, instead just keep doing what needs to be done. Sushama is a warrior like that.

I also wanted most of her scenes to be silent ones. After a point, Ajji starts to alienate the viewer as well. The conflicting thoughts inside her heart and mind are hidden from her family at first. And from some point on, from us as well. I needed her to become a stranger to the viewer too – the one who has been rooting for her all along. Until things reach a point where we don't realize when she decided to don the guise of a prostitute to go after Dhavle. To achieve that, a lot of what Ajji was going through would have to happen inside her head and heart. I always trust the camera to catch glimpses of that through the actor's face.

We wrote numerous ‘inner monologues' for Sushama. Most of the silent scenes where she doesn't express much verbally, I made her speak her inner monologues silently inside her mind. The small inflections in her face, subtle twitches of muscle, that odd fleeting emotion in her eyes – the camera was to catch them all without her being too conscious of it. This was an experiment that seemed to have worked. There is much power in Sushama's silences, precisely because they are not really ‘silent', they are simply non-verbal.

In general, how was the casting process like for the film? Can you tell us a bit about Sudhir Pandey and his part?

Finding actors was not the challenge for this film. The challenge was to find the Women who would epitomize / believe in / stand for the things this film seeks to say. Each of the actresses – and female crew – in this film are champions. They are strong – both within the paradigm of the story, and in their own lives – and they are fighters. We didn't form a ‘cast' in this film, we formed a feminist army. The few men who were a part of this cast seemed to be in touch with their feminine side. I don't mean that glibly. There is a deep reservoir of empathy and strength in all the men who complemented the women in this film. If there wasn't, the fabric of this film would've been compromised.

Abhishek Banerjee is Dhavle. He is also one of the film's casting directors, along with Anmol Ahuja and Manuj Sharma (who also plays Umya). Abhishek and Manuj share a deep comfort, having been buddies for years. I merely pushed their camaraderie into a dark, borderline-homo-erotic space, to be able to achieve the disturbing dissonance of the prolonged ‘mannequin rape' scene.

Vikas Kumar who plays the cop is the complete opposite of this character in real life. He is kind, gentle, generous and pure of heart. He has a little daughter, and had to shed that skin to get under the skin of his character. It was painful, but he's a warrior.

Sadiya Siddiqui has been one of my favourite actresses for years. I needed someone who looked petite, someone a man would think he could easily bully, but she was a storm on the inside, a storm you better not get in the way of. Sadiya brought that to Leela.

Smita Tambe is one of the most powerful actors in the game in India today. She understands the camera and how to inhabit the frame unlike most. She plays Vibha – the most conflicted character in the film. Vibha needs to move on with life, and doesn't allow herself the luxury of grieving, even when faced with the grim horror of a raped little daughter.

Sharvani Suryavanshi was the biggest reason this film manages to move the viewer. She understands things much beyond her age. As little Manda, she may not have completely understood the physical repercussions of what her character's been through, but through intelligent questioning and an unbelievable human instinct she understood the difference between a ‘good touch' and a ‘bad touch' and what we required of her. Watch out for this gem.

Shreyas Pandit plays the father Milind – the only man in this film's universe who is ashamed perhaps of being a man, but is unable to show it. He was a proxy for me perhaps. When he says ‘sorry' he does so on my behalf, apologizing to all the women in the world for the centuries' old obnoxious ways of men.

Which brings us to the actor you ask about…

Sudhir Pandey – another of my all time favourites – plays the Butcher. He's arguably the only senior actor I know who brings a child-like curiosity and enthusiasm to the set. He chopped and carved meat, got splattered with goat shit and blood with unquestioning commitment.

The Butcher is the antithesis of Ajji. He is a simple-minded, gentle male, providing ironic contrast to Ajji's complex, brutal female. Ironically again, he inhabits a world of blood, carcasses, death, but is arguably the most empathetic man in the universe of this film. I like playing with these ironies because they allow the viewer to access a deeper idea of non-judgmentalism. I don't allow you to judge him for what he does for a living, because I juxtapose it with what he does for Ajji.

Also, the idea of chopping a carcass of a goat into its parts – legs, head, torso, entrails – went hand in hand with the idea of tearing the mannequin too into its parts. That horrific act turned Dhavle into a butcher too, to whom every female body – alive or lifeless – is merely meat… to be consumed.

The film features a number of violent, exploitation scenes, which you portrayed quite graphically. Why did you choose this approach?

Three reasons. None of them very obvious.

One.

We live in a grim world. We often seek ‘escape' from cinema. I wanted to use this medium (and especially this film) to subvert that expectation. I wanted to give the viewer the opposite of the escape – I wanted to ‘trap' them in the same grimness that the silent majority of our country (and the world) have to live with each and every day of their lives. We wanted this film to be a true mirror to what we have become. And the truth is brutal. The truth is ugly. The truth is something we do not want to be reminded of. The agenda then was to give the viewer what they did NOT want.

Two.

This film tries to explore the (very) complicated idea of ‘justice'. Is it only a collective morality that can decide what constitutes justice and how it must be meted out? Or can an individual's idea of right and wrong, and his / her personal circumstances also play some part in the matter? “Ajji” explores this very contentious question through a portrait of a woman caught in these fractures. I like exploring the larger questions that trouble me through micro-stories of voiceless individuals. The friction between the macro and the micro this causes, always throws up something dramatic.

Three.

I am not a woman. But to tell this story convincingly, I had to become a 9 year old girl, a 30 year old woman, a 60 year old one, as well as a prostitute. I had to think like them. I had to feel like them. Not just emotions. But also physical pain. I had to feel what periods might feel like. I had to feel what forceful violation might feel like. What rheumatoid arthritis might feel like. What an unwanted pregnancy might feel like. The making of this film made me feel physical pain in ways I'd never felt before. But I needed to go through that to be able to transfer the horror these women face, to the viewer.

And for that, I had to sometimes resort to showing the horror the way it might have played out.

My cinematographer (Jishnu Bhattacharya), my editor (Ujjwal Chandra), my associate director (Pooja Chauhan), my co-writer (Mirat Trivedi) and I went out of our way to try and ensure that only the HORROR of the act transfers. The choices of what to Show and what to Evoke were taken with much care. When the ‘mannequin rape' scene begins, there is some ‘play' between Dhavle and Umya that does elicit a chuckle or two. I needed that. When a man in the audience chuckles at the top of such a scene, then when he realizes just what it is this scene is intending, he often gets plunged into a guilty silence. And Guilt is something I wanted to slap all men in the face with. We are all complicit in every rape in every corner of the world, because we allow it by not trying actively enough to stop it. And I was hoping this scene with the mannequin would achieve that.

What is your opinion about the depiction of violence in cinema?

My pet peeve with violence in most cinema is that it is often glorified. It is, unfortunately, made to look ‘sexy'. In most genre films, even when a woman is seeking revenge for rape, the camera will linger on her body, informing us of how attractive she is. Making us – ironically – ‘rape' her with our minds. These double standards are what I wanted to subvert with ‘Ajji'.

We firmly stayed away from the falsehood of ‘sexiness' in such a paradigm. We consciously avoided any slow motion shots of violence. And any rising background score when violence is exercised by any character in the frame. Both devices trouble me when I watch them in others' films.

The film presents three social remarks: The corruption of power and the ties of politicians and “the capital” with the police, the way people perceive the elderly and self-justice. What is your opinion on these subjects?

I'm driven sleepless by injustice and inequality.

And I'm endlessly curious about death.

These two preoccupations have shaped most of my thematic choices. There's one more theme I'd love to make films about – Sex. But I'll get to it when I can explore it in ways that will not merely titillate the viewer but in fact raise questions. More on this when I get to it I guess.

I think we as a species, a nation, a community, we don't look into our souls often enough. We humans pride ourselves in our ‘consciousness', our emotional superiority over other creatures. But most of the time, we leave it at that, revelling in the vanity of this superiority, never pausing to look at ourselves for what we really are – the stupidest, most destructive, short-sighted species on earth. Why? Because I suspect we're shit scared of our own selves.

So its not just our political decisions that I'd like us to reconsider, but our social, economic, industrial, consumerist, environmental, emotional and philosophical ones as well.

The three major power centres in ‘civil' society as I see it, are Politics, Industry and the Uniform – be it police or military. A politician has the power of (informed or not) Public Opinion. An industrialist / businessman has the power of Money. And the man in uniform has the power of the Gun. Power attracts power, mostly because power is unstable, and causes infinite levels of insecurity. Often public opinion is won by force or is bought. Often money needs firepower to keep it from trickling down the food chain. And often firepower needs policy making and money to maintain its juggernaut of death.

How can these three not be joined at the hip?

And how can an individual in this very civil society who has no access to Public Opinion, Money or Justice not take recourse to some form of self-justice? (this is not a prescription, mind you, merely a questioning)

Of all of us, it is the elderly who are the closest to Death. And I like to explore death intimately. In the elderly, I detect predominantly one of two things – either a surrender to the inescapable eventuality of demise… or a heightened cynicism, which brings with it a certain fearlessness, that can push the person into places of extreme. Like Ajji was.

Jishnu Bhattacharjee implements the noir aesthetics of the film impressively. Can you tell us about your cooperation?

This is Jishnu's first feature film.

Yes there is a noir aesthetic. But we tried consciously to not fall into the traps noir brings with it. We didn't want the film to look or feel like quintessential noir. Instead, my constant endeavor was to make something else our preoccupation… something I call “Cinematic Filth”… to see the world of Ajji in some sort of Constant and Active ‘decay'. This would – I theorized – presuppose a noir aesthetic, and we wouldn't have to seek it too consciously. And that would help us, perhaps, avoid the clichéd pitfalls of generic noir.

We tried not to make a spectacle of poverty (something many Indians accuse Indian ‘festival films' of doing), but instead tried to be true to the protagonist's poverty while simultaneously making it look cinematic. Not by beautifying or romanticizing it, but by simply making it look visually interesting (for the lack of a better word).

This was easier said than done though. To be true to the world we were creating – and shooting in – we had to perforce be true to the light sources there too. This made Jishnu's life challenging, and he rose to the challenge. He has used everything from a cigarette lighter's flame to (only) moonlight to flickering tubelights to light the most critical scenes in this film.

We share such a trusting camaraderie that there are times he vetoes me completely as to where to place the camera, telling me – with no apology – that my idea is a shitfuck one, and he'd rather place the camera elsewhere. Jishnu is a delight.

Can you tell us a bit about Mangesh Dhakde's music, particularly the track included in the scene where Dastur comes to Dhavle's place?

Mangesh is one of his kind in the current cinema firmament in India. His music – in my films and in those he scores for one of my contemporary filmmaking heroes, Umesh Kulkarni – is strangely local and global at the same time.

I'll explain.

There is so much shared information in all our unconscious minds that we – as creators and consumers – can find resonance in one another's mythologies and experiences. This shared understanding gives rise to archetypes. I'm very interested in these archetypes, in what makes a story about a little corner of Orissa resonate with a Dutch musician in New York. What emotional experiences do these two share? Hence, what are the elements that can make a story culturally specific in details yet emotionally universal in appeal? I strive to make every story I tell – from my children's books to my forthcoming novel, to my films – accessible. The meaning of that word might be up for debate, yes. But to my mind, in a very broad sense, if a story can communicate its deeper social / political / demographic / philosophical intent while being ‘engaging' – be it via thrill, emotion or humour – it will always enable audiences of all kinds to ‘access' it.

One of my few recurring collaborators – Mangesh – seems to get it, even though I've never verbalized it to him.

He uses instruments and arrangements and chord progressions sometimes that may not be inherently Indian, but make the proceedings of my film feel more contextual to the content than I could have imagined. His musical choices are universal, even though his emotional core is deeply Indian. I know I sound somewhat vague, but this is the closest I can come to trying to identify what it is about Mangesh Dhakde's music (especially for ‘Ajji') that makes the cinema he touches, unique.

Interestingly, the particular track you speak of, is not music composed by Mangesh. It's a ‘Shiv strotam' – a holy hindu chant to the lord Shiva that is a staple in many homes where Shiva is revered. It was Kaamod Kharade – the sound designer – who worked that into the soundscape of that scene. There is a constant presence of devout hindu religiosity in and around Dhavle's life.

Irony, again.

Many of the so-called right wing faithful in this country don't truly understand the tenets of the religious beliefs they propound. They twist religion to their political and personal prerogatives. Dhavle is one such.

What is your opinion about Hindi cinema at the moment?

I've been sensing a more global culture percolating into every kind of cinema in the world today. There is a touch of European storytelling even in a quintessentially Iranian ‘A separation'. Some cultural boundaries have collapsed. More are to follow. Also, there appears to be a shift from dialogue-intensive storytelling (the kind India's oral storytelling tradition relied on) to informing through ‘imagery' and ‘sound' – which are in essence the true strength of cinema. As a result, every region's cinema is slowly becoming less and less reliant on ‘subtitles' or translators, and crossing over boundaries in a way that even the most well-meaning diplomats cannot do. Films, I sense, will soon become every nation's – and region's – truest ambassadors.

India is unique. It has over 30 official languages. Almost half these languages have their own official film industries. No other country in the world is this heterogeneous with the languages their films are made in.

The regional cinemas of India are following this zeitgeist I mentioned above – be it Assamese or Marathi or Malayalam or Tamil or Gujarati films.

But there seems to be some resistance from the mainstream Hindi cinema. Hindi cinema has relied on spectacle and the star system for so long that it cannot (and never has) been able to reconcile with much change. Even if the stories have changed (as they ought to, since there's a socio-cultural shift from generation to generation) the reliance on spectacle and the ‘star' has not. And its ok I guess, since there is a particular need this cinema has always tried to fulfill. This cinema will always have its loyal audience, because its viewers seek very specific things of it.

Broadly, I haven't formed much of an opinion about the mainstream in Bombay cinema, because I don't seek to inhabit it. Most of my films might be in Hindi, yes, but I think the similarities with the mainstream end there.

Although that brings me other challenges. I don't often get seen as the artistic filmmaker I'm trying to be because I don't make regional cinema. In fact, I don't have roots in any state of India, since both my parents came from Pakistan during the partition of India. The only language I've ever spoken outside of English has been Hindi. And so I'm cursed to make films mostly in Hindi most of my life. And might always be asked the question you just asked me!

Can you give us some details about your future projects?

My next feature ‘Bhonsle', with Manoj Bajpayee in the lead, is in post-production right now. ‘Bhonsle' is roughly a feature length exploration of the same themes we explored in our short ‘Taandav'. It's a bigger, broader, much more ambitious film than ‘Ajji'. But once again, in it, we've tried to explore some of the more disturbing socio-political issues and questions of our times. If “Ajji” turned its lens on the gender discourse, Bhonsle focuses on the immigrant debate. We've tried to throw up a difficult question – who's an insider, and who's the outsider, and who decides that?

My book of poetry ‘Disengaged' releases later this year.

Another short film ‘Happy' is shot, cut and ready. I'm waiting to make some of the money I need to finish the sound.

I'm halfway through writing my young adult fiction novel for Tulika Publishers. It too is slated to be out by the end of this year.