The slow-burning drama, as dictated nowadays by the style of Hirokazu Koreeda, is one of the most dominant genres in the Japanese movie industry. Takashi Saito makes his effort in the category with a film that follows its general rules, but also soars with a “subtle” tension deriving from the protagonist.

The Voice of Obo is screening at Japan Film Fest Hamburg

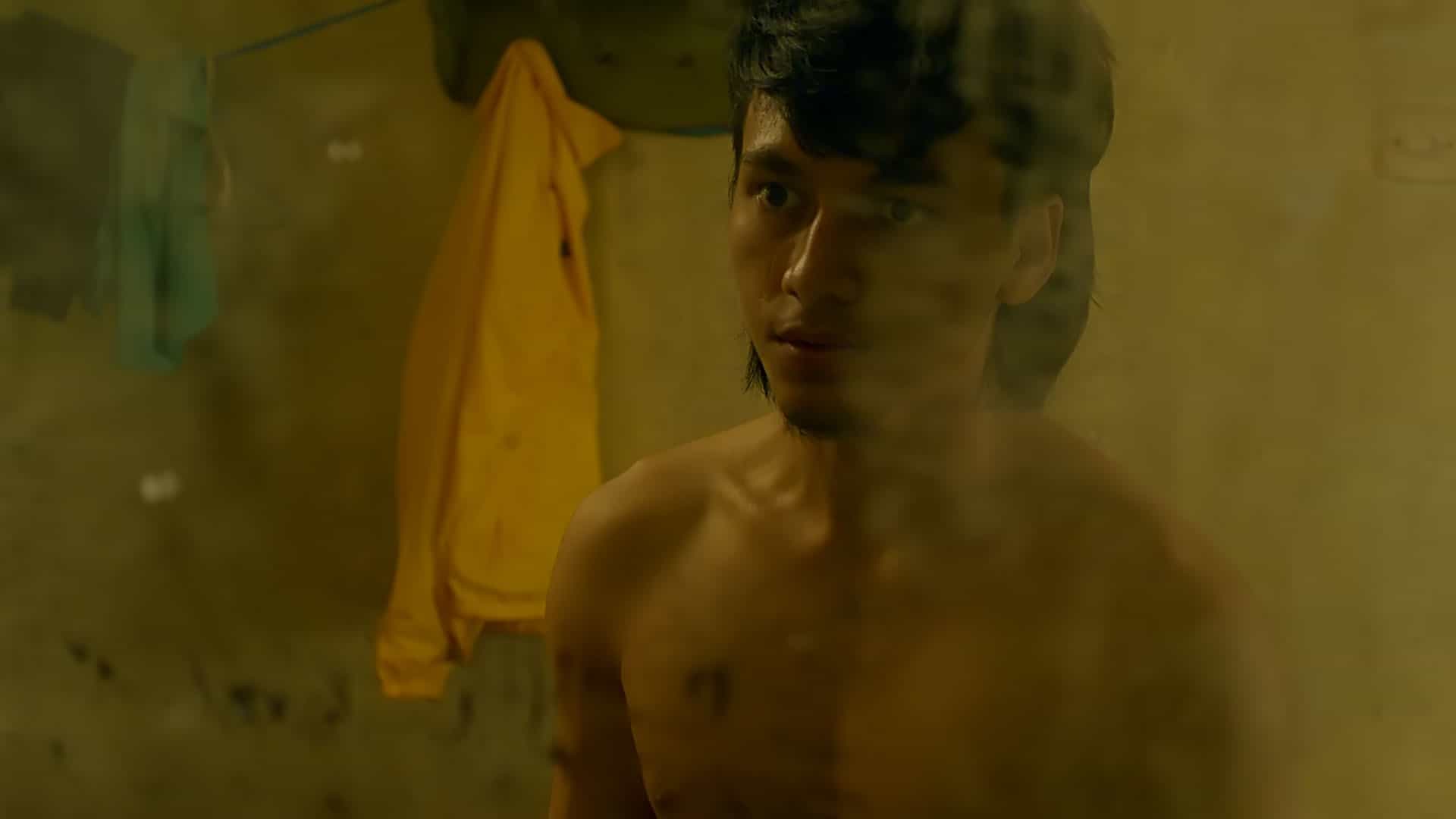

Shuta is a former boxer, and the embodiment of what society calls a loser. He cannot keep a job due to his temper, he mistreats his girlfriend for the slightest of reasons, and he seems to take no responsibility for anything that happens to him, blaming an invisible force for his troubles. His tendencies reach an apogee when his girlfriend announces to him that she is pregnant and she is keeping the baby: he decides to abandon her and leave for his hometown and his mother's house, who used to be proud of him but now treats him as a nuisance. Soon, he finds a job carrying gas cylinders, along with Moriyoshi, a middle aged man who seems to be the personification of what Shuta's future would be if he keeps moving in the same path. The two form an unlikely bond, in the midst of two rumors: one that Moriyoshi is a murderer, and another, that anyone who hears an unusual voice echoing from the mountains, dies Eventually, Shuta is forced to look himself in the mirror.

Takashi Saito directs a film about the people that society has kicked to the side, by focusing on a man who cannot handle his present, but even more, his future. One could say that the main theme of the movie is the depression deriving from all the above, but Saito does not portray his protagonist as a victim of circumstances, but of his own character and tendencies, and particularly his inherent escapism and his constant avoiding of taking responsibility.

Life, however, does not seem to stop throwing trouble towards him, which one could also perceive as chances to finally become responsible, and in essence, to change. Saito seems to state that in order for that to happen, rock bottom has to be reached first, and that is where Shuta's life is guiding him. The concept of The Voice of Obo also seems to state that help will not come from “above” or from anything supernatural (the invisible force I mentioned), but from within, when one acknowledges his shortcomings, his situation and deals with it.

Shuta as a character embodies all the aforementioned comments, but I have to say that the actual meaning of the movie is a bit hard to discern, to the point that I am not sure if the way I perceive them is the correct one, at least for the most part. This faults the narrative somewhat, as the film demands some explaining (or at least someone who is closer to the Japanese mentality than I am).

The undeniable fact, though, is that there is energy here, mostly deriving from Shuta's evident tension, which seems to be emitting from every pore, occasionally finding a way out through violence. In that fashion, Takashi Yuki delivers a great performance, equally artful in the seemingly peaceful but essentially tense moments and in the ones where he erupts. Shun Sugata as Moriyoshi presents a radically different character with equal prowess, in the role of an unlikely mentor (of sorts).

Kota Negishi's cinematography focuses on realism, without any exaltation, as per the rules of the Japanese indie drama, with the same applying to the editing, which dictates a rather slow pace, in art-house style.

“The Voice of Obo” does not stand out much from the plethora of similar Japanese movies, but definitely deserves a watch from fans of the category, particularly for the conception and the implementation of the main character.