Mohammad-Ali Talebi is an Iranian director. While studying film and TV programme directing at the university, he made about ten short films for children. He begun his career in TV documentary and continued to work for the television writing and directing over 50 video programmes and various educational, documentary and fictional pictures. He has been directing films since 1986 and “The Finish Line”, while his most renowned works include “The Boot”, “Bag of Rice” and “Willow and Wind”, based on a script by Abbas Kiarostami.

On the occasion of “Bag of Rice” screening at the 27th Art Film Fest Kosice, we speak with him about working with children, the film and his career, how he was “re-discovered” by Mark Cousins and the BFI, Iranian cinema, and other topics.

Why do you like to work with children?

I do not only work with children, I have some films with teenagers and some with female leads. The reason I choose these groups is that I feel they are the most fragile and vulnerable of the Iranian society. Going back to your question, I used to work for the Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Youth, it is a very famous institute, a number of famous director have worked there, and that is how I started working with children.

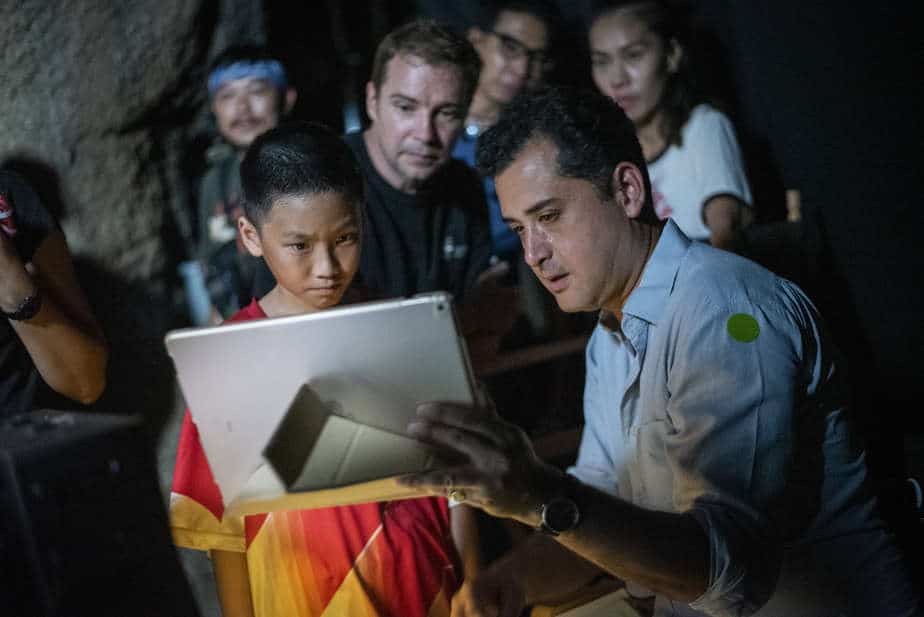

How difficult is it working with children, and what kind of qualities should a director have in order to make this work? Patience?

Making films with children goes back to around 20-30 years ago when I was younger and I was more patient and I had more energy to work with them. Of course, working with children is very complicated and now that I have grown older, I have moved more towards teenagers, who are easier to work with. But going back and remembering of how I was working with children I would say it is a very sensitive topic, it is probably the most difficult job in filmmaking because children have their own ways of doing things. They do not always do things the way you want them to and you have to be flexible, not only you, but your entire crew has to be dedicated to letting the children do the best for the film. Therefore, you would go to the set and you would have a specific mise en scene and a specific way of shooting the scene but then the child comes and changes it, so you have to be flexible, to adjust yourself to the kid. It is a very sophisticated procedure that requires a lot of patience, as you mentioned.

There is a scene where Masoumeh loses her glasses and helplessly searches the pavement for them, but no one seems to help her, apart from little Jairan. In a later scene though, we see a man on a bike helping her carrying her bag of rice to her destination. So, what is your view of Iranian people, are they good or bad/indifferent?

It is interesting you are asking me this, because in many of the screenings of the film outside Iran one of the most common questions I was asked was if the Iranian people are as helpful as they appear on the movie, because there are many scenes that people help each other. For part of the audience, it felt as if I am exaggerating regarding the friendship and connection between them. What I wanted to show is this connection and the helpfulness people show to each other. The scene you mention is a quiet one, there are not really many people passing by, but even then there is the young boy that helps Masoumeh to find her glasses.

The film also functions as a road movie. Why did you choose this approach?

When I was making this film, it was a very specific time for Iran, just after the Iran-Irak war and many things were sold through coupons; Tehran was just past years of bombardment. Therefore, I did not want to stay in an apartment or a studio, I really wanted to show what people are dealing with, but at the same time, I knew that if I became too critical, I could not make the film. Therefore, I decided I would take this bag of rice as an excuse for traveling into the city, to document how people really live. Just by going from one place to another, you see an old woman dealing with trouble, many mothers whose husbands are dead, we do not know why, but we know the husband has passed away and coming just after the war, the reason becomes obvious. I was really trying to go to many places in Tehran in order to capture and document the life of people back then and that is why it has that structuring of traveling in order for me to depict as much as possible from the city

How was the casting process for the film, particularly considering the majority of the cast was either small children or very old women.

Since I worked with non-actors, it was a very complicated process. In the case of children, I usually go to a lot of schools and kindergartens. For this specific film, I went to the same neighborhood; I was looking for kids in the neighborhood. Then I found the main actress and went to see her family, and found out she had like 8 siblings. There were not in my script but when I saw them, I thought it was interesting to include them in my script. In essence, my script changed according to my discoveries of the characters and the person behind them. I also wanted to include the parents but the mother had to cook for all those people in her family and the father had to work so they did not have the time. Her aunt's husband acted as the kids' father but I always pick people from the same setting so this kid belongs to this setting. For example, when the little girl had breakfast, she knew how to go about it in this setting and she felt very confident, because she belonged to those streets.

In your years working in Iranian cinema, what kind of changes have you experienced?

Starting from the revolution, about the time I started working, I would say that the first years were quite complicated, because the revolutionaries did not even believe in the existence of cinema. So, imagine how difficult it is to work with people who believe that the entire art of cinema should be discarded from society. So I think the first years of the revolution were years of recession, with the ideological people who were trying to stop us. Those were very difficult times. But as time passed, slowly there were some more open-minded people coming to power in cinema organizations and what happened was that, ,because Iranian cinema included some good professionals before the war and these people were eager to give us some space to work, after that, this whole golden era of Iranian cinema begun. Some of the bigger names were prized and the country's cinema was introduced to the world. A number of Iranian films went to many festivals, even Iranian cinema influenced the cinema of countries such as Turkey even all the way to China. However, like any country in the world, this golden era is beginning to fade. It is still there, you can still see works of quality coming out, but I feel these are the last attempts of an era that is vanishing.

Can you tell us a bit about your cooperation with Abbas Kiarostami?

Kiarostami is one of the masters of Iranian cinema, but he also worked for the Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Youth, just one generation before me. Therefore, when he was making films, he had students and trainees who were learning from him. At the time, he was working on a documentary that included a short film. As a trainee in the Institute, I directed that part, so we got to know each other and we came closer after this. He told me about one of his stories, I asked to read the script, I really loved it, and I asked him if I could actually direct it. He agreed and this is how “Willow and Wind” came to be. I directed it and I was working with him closely from the script to the production and the finished film. Then we became close friends, and since we were living close to each other, we frequently visited each other's flats, and he was bringing all his books of poetry and I was reading them. We really became very close and that is how our relationship went forward.

Can you give us some more details about your cooperation with BFI, which actually reinvigorated your career?

I had most of my films collecting dust in my attic at home for many years. Nobody was asking for them, but at one point, I started receiving some emails from BFI, from a person called Mark Cousins, I did not know who he was. They kept sending these emails, but I was not reading them, and I was talking to my wife saying that this must be some kind of spam. For 3-4 months, they were just writing to me asking for my films but I did not realize it was a serious offer. After 3-4 months, I talked to a friend and told him that I received these emails from Mark Cousins and that I thought it was a fraud. My friend then said that Cousins is a very reputable film critic, and asked me to send him the emails (laughing). I did and he read them and explained to me about BFI and that is when I realized they really wanted to cooperate with me, to screen my films as a retrospective in BFI. I did not have any good versions; I just had these positives in the attic. But I shipped them those and then they invited me for 20 days and I was in the UK and they screened 3 of my films, “Bag of Rice”, “The Boots” and “Willow and Wind” in 20 cities. I was very surprised because people were laughing with my films and were emotionally touched and I really felt that, after many years, my films were finally noticed again.

Even yesterday in the screening (June 20 in Kosice), I was happily surprised that for the whole of the screening, people were laughing. They were laughing so much actually, that I felt it was a Chaplin movie playing. Although in some other screenings it was less, even then, after the film, they were clapping for a long time and I was really surprised that after so many years, my films still manage to connect with the audience.

Coming back to BFI, the reason for Cousins discovering my films was because he was doing a huge project called “Cinema of Childhood” and he was exploring the entire history of films that focused on children and in the end, he chose a thousand films from various countries. He chose 36 films out of those and then 17 to be screened in BFI . Four of these were from Iran, the three of mine I mentioned and the last one was Jafar Panahi's feature debut, “The White Balloon”. The reason they chose me to invite was that most of the directors whose films were chosen were already dead (laughter), like Tarkovsky and Ozu.

Are you working on any new projects at the moment?

I moved to Slovakia about a year ago and now I am writing a script for a feature film taking place here, about three teenagers. I am doing a long research, talking to a lot of young people, and by talking to them I am polishing my writing again.