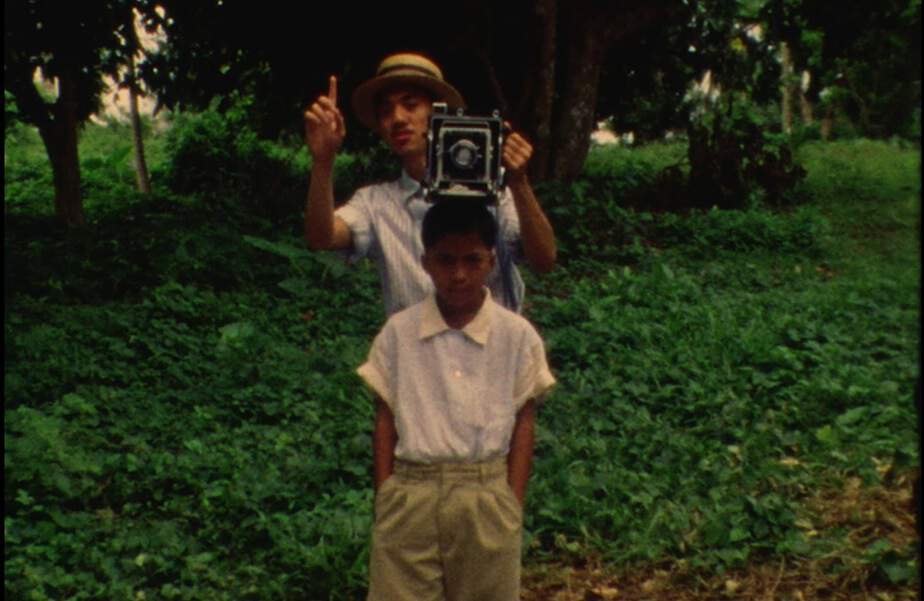

“Big Boy” is Philippine director Shireen Seno's first feature film. An ultra-low budget independent film shot on Super 8. As a coming-of-age story, it tells the story of a young boy, Julio and the business venture initiated by his parents. Julio's parents wish him to become an ideal man according to their standards. In other words, Julio has to be tall like an American. They design an elaborate method to achieve this. They try to make the boy taller by pulling his limbs, they make the boy drink growing oil that they made themselves, and the boy has to stand under the sun every morning. The growing oil seems to be effective, so the father tries to capitalize it and sell it to other villagers. Everything seems to work out fine, until one day Julio stop growing.

Watch This Title

The description of the plot of the film might give the impression that the story is about how the boy fights against the wishes of his parents at first, and after his adventures throughout the movie, he reconciles with his parents and learns some lessons about life. This, however, is not the case at all. In fact, “Big Boy”‘s loose narrative structure, its uses of amateur actors, and its documentary quality, make it more akin to Francois Truffaut's “400 Blow”s.

Similar to Antoine Doinel in 400 Blows, Julio tries to break with the growing routine imposed on him by his parents in several occasions. Julio's last “escape” echoes Antoine Doinel's escape in the french film. Just like Antoine, Julio runs to the shoreline of the sea at the end of the film. However, the film doesn't stay with Julio and his rare moments of freedom for too long. It cuts to a mobile shot on a boat. We see the Mindoro Island, where Julio and his parents live, appear from right to the left of the frame. Instead of focusing on an individual person, Seno reminds us that we are part of a larger context, both natural and historical.

Unlike Antoine's personal struggle, Julio's journey accidentally intertwines with the colonial history of Philippine. Seno never portrays stereotypical political or historic events in the film; instead, she uses daily interactions to show U.S.'s colonial legacy on Philippine. For example, at one point we see Julio trying on a raincoat. He cheerfully asks his mother if he could fly after wearing the raincoat, because it is made of parachutes. Military equipment turns into a daily object and stimulates one kid's imagination.

Indeed, Seno's camera always stays with her characters, especially with the kids. The camera always observes keenly what's unfolding before it. In a scene, we see the camera focus on a wild pig coming out of a pond and walking past the camera. This moment doesn't have any narrative function; in fact, I don't think any character of the film is aware of the existence of the pig. However, the camera and our attention are grappled by the presence of this creature. We, too, share the curiosity of the camera and want to figure out what does the pig want to do next. “Big Boy” is full of these moments. The result is that the film has an interesting texture, in which loosely observational footage is interwove with scripted materials. We constantly move between the rhythm of film narrative and the rhythm of daily interactions “performed” by the actors. We don't learn Philippine culture through these observational footage; instead we stay with the characters in their immediate living situations. Seno let us see the characters' worlds at their eye-level, without turning these moments into specimens of “Philippine rural life.”

More specifically, these observational footage is mostly about children's play. We see them playing hide and seek, hanging around the house, and fighting each other with living crabs (and get bitten by them). It is a world with their own rules, and without others imposing expectations on them. The concept of getting ahead of others is obsolete in the children's world. As if to emphasize the differences between the children's world and the adult' world, the children's play sequences are mostly done without dialogues. We don't need words to comprehend what the kids are doing. The only thing we need to do is to see their faces and gestures. Only at a few moments, Seno inserts non-diegetic music, mostly folk rock, to add a layer of nostalgic feeling to the scene.

Not only does Seno want us to see in a fresh way, she also wants us to hear more attentively. In many scenes, sounds are as important as images. The film starts with a black screen and we can only hear an American skin care product commercial playing in the background (we are not sure whether the advertisement is diegetic or non-diegetic). We can only hear two American women talking about each others' facial skin and which skin care products they should use if they want to look good. We hear one woman saying that she wants to let herself looks whiter. This brief sound bite sets the theme and tone of the film. The accent and speaking style of the two women reminds us about the U.S. in the fifties, which adds a nostalgic feeling to the film. And just like Julio's parents, these women desire to change one's looks through external methods. More importantly, this information is set up merely through sound.

Although the film shows us that by looking and hearing attentively, we might see the world in a new way, it also lets us know that there are mysteries in the world. There is something that will always be beyond our reach. After the opening sequence, a bird's eye view shows a naked man rocking back and forth. On the soundtrack, we hear a woman moaning and the creaking sound of the bamboo bed. We never see the woman, but from the sound she makes, we realize that they are a couple and are having sex. This could be the moment where Julio, our main character, is conceived. Then, we hear someone knocking beneath the bed. The man is puzzled at first, but then he starts knocking on the bed to communicate with the being at the other side. He is in profile and we see him slowly smile. Throughout the scene, Seno emphasizes sounds over images. Most of the time, we can only infer what's happening in the scene through our ears. Moreover, there is still a mystery left unresolved after the scene is over. We never find out what is on the other side and what they have communicated. In this scene, the characters know more than the audience do (we never know why the man is smiling). Unlike conventional films, “Big Boy” doesn't intend to solve the mystery. It is not a goal for the characters or us to resolve. This makes Seno's film interesting. Mystery and uncertainty permeate this film.We can never resolve this situation, and all we can do is to perceive the world attentively.

Big Boy shows us a way to treat history and memory in film. Without turning daily objects into moral lessons, cinema has the power to show to the audience, a unique way to perceive the world. And “Big Boy” does just that.