By Wally Adams

Tokyo artist Hikaru Fujii — whose work encompasses documentaries, workshops and theatre — primarily focuses on national consciousness and history related to Japan. For most including this reviewer barely familiar with his work (most of which is exhibited in Japan), the linking thematic interest of identity and how events collectively shape it is already at least partially evident just from reading some of the titles of his work including “Aomori City Archives Exhibition: The construction of history is dedicated to the memories of the unnamed” and “Japan Syndrome: Art & Politics After Fukushima”.

For “Educational System of an Empire” however, the focus is on Japan in regard to Korean students (double-filtered through an American documentary). In particular, Japan's role as colonizer and how Japan's increasingly fascistic (both in how it was run and the values it extolled) education system of the 1930s that followed alongside wider political developments helped shape that.

“The Educational System of an Empire” screened at Japanese Avant-Garde and Experimental Film Festival 2019

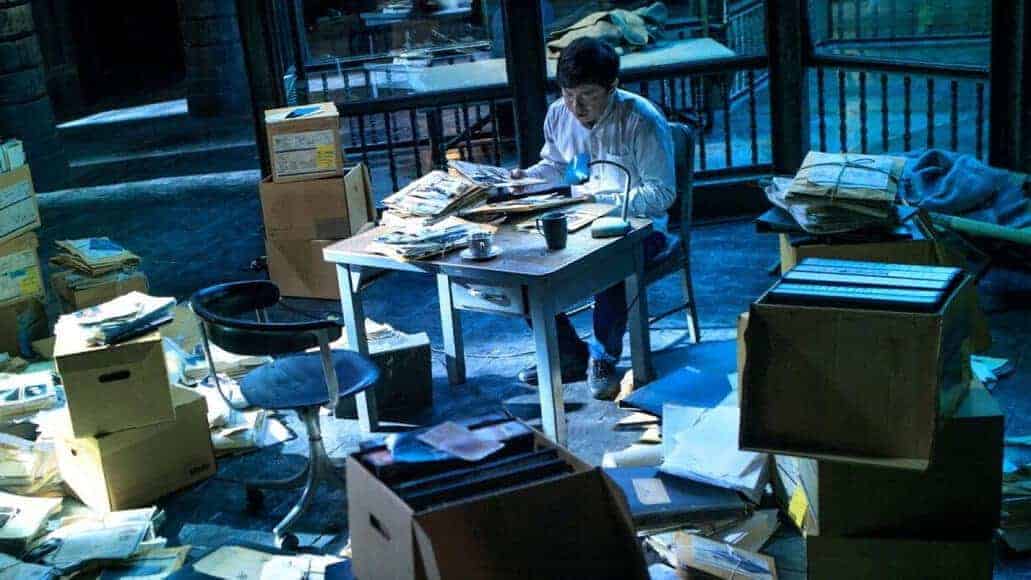

For that purpose, 23 South Korean students (presumably university) are gathered in minimalist blank studio surroundings then directed (both in physical and filmic sense) in groups to follow instructions on movement, watch different documentaries and relay what they saw to each other.

While it's indicated that the students are shown several different documentaries, the only documentary visibly (and extensively) shown within this documentary is an old (and generally accurate) US War Department propaganda film with the slightly different title “The Educational System of Japan”. However, it is clearly not the only one shown to the students (what else was shown is deliberately kept unclear to us), as theirs appear to be about life and abuses during the occupation of Korea and probably the 2nd Sino-Japanese War as well.

It should be noted in this case however, that the developments determining how Japan came to view Korea and their conquest had already started decades prior even if the creeping internal radicalism further exacerbated them. That being said, it might have been interesting to have shown more about how the Empire's educational system was implemented in Korea and its effects, as this documentary has only one very brief part showing footage from colonial Korea.

As it is, in addition to being given various instructions like to “lay down like corpses,” the students are then coached to improve their coordination (“synchronize the walking”). That way it's closer to matching that of the archival footage of physical education, patterned after the military as of course fully matching it would require essentially military drilling (even if nearly all South Korean males DO undergo military service sometime between 18 and 28 which most if not all of these males fall under).

In probably the most fascinating part of the documentary, 1930s footage of educational indoctrination towards primary school Japanese students on what would seem to be routine matters like art and calligraphy are juxtaposed with current Korean students describing torture and executions (and sometimes both in one as with live burials), and reenacting torture like waterboarding towards each other that was often done by people brought up through the titular educational system.

The curious thing about this aspect is how casually and buoyantly the students usually describe it all. And indeed from the very beginning the students are shown simply being like most other modern students — nonchalantly chatting, teasing each other or of course just looking down on their cell phones. I won't claim that I'm completely aware of all the director and staff's intentions here (mainly regarding the extant of expectations for these students to feel involved, unified or “awakened” so to speak), but I can say that this is nevertheless an understandable experience and resonant issue.

Seeing them is reminiscent of a personal university activity and project for a class on the Cambodian genocide with similar instructions and reenactments, striking a delicate balance or keeping students involved and even entertained to an extant while still instilling and maintaining the gravity of the subject matter. Both here and there, for the most part, the students were often visibly perplexed, embarrassed and even amused at first. But in the end, they seemed to recognize a sense of purpose and appreciation in connecting the past to the present and future.

The distance young people are increasingly having from history that's deeply affected entire countries' national and ethnic psyches is indeed an important and complex matter. But in some ways, that could also be viewed as a good thing in helping to settle, mitigate or end old scars and animosities and make mutual acceptance and cooperation easier. On that note, “Empire” ultimately conveys a general sense of optimism despite the dark themes that in other artists' hands present (and sometimes brandish) a fiery, negative or combative air about them. But that's also in part due to the general lightness of the treatment here suggesting this is — or hopefully will be — just a starting point in nurturing critical and involved but still understanding attitudes in the youths featured and by implication today's generation altogether.