One of the many consequences of the American occupation in Japan after WWII was the resurgence of Yakuza, particularly in areas where US naval bases were situated, with its members profiting significantly from the black market, which was a direct result of the food rationing the occupational forces have decreed. Basing his script on a novel by Kazu Otsuka, Shohei Imamura uses the aforementioned setting to place the story of “Pigs and Battleships” in the small fishing port of Yokosuka, in an effort that went so much over budget that Nikkatsu decided to ban him from shooting movies for two years.

“Pigs and Battleships” is screening at Japanese Avant-Garde and Experimental Film Festival 2019

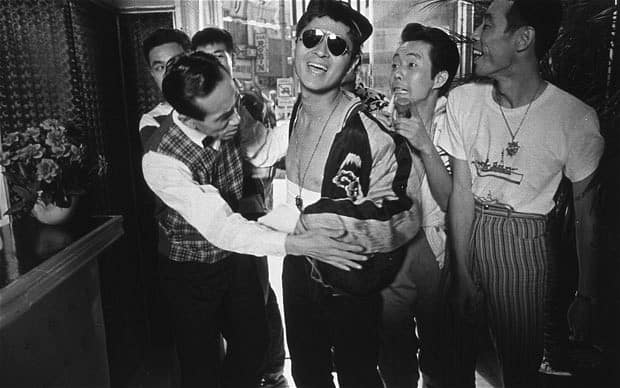

The story takes place mostly around the red light district and the docks of the area, where the two main protagonists, Kinta and Haruko, try to build a future together, against all odds. Kinta is a low-level Yakuza who is put in charge of the Himori gang's new endeavor, pigs. Kinta has to fatten them up in order to sell their meat to the Americans, and goes about his job in distinct Yakuza style: forcing poor locals to “loan” him money to cover the expenses. At the same time, he has to deal with his hypochondriac sub-boss, Tetsuji, who is convinced he has stomach cancer and is basically useless, despite the continuous faith and support by his subordinates. A dead body that Kinta eventually has to dispose complicates matters even more, since the rest of the members of the gang “groom” the somewhat simple Kinta on taking the blame in his boss's stead.

Meanwhile, Haruko, Kinta's girlfriend, is being rent out by her mother to American sailors, in a tactic that seems anything but uncommon in the area. The two of them are in love and Haruko wants to make Kinta leave the Yakuza while he wants her to stop dating Americans for a fee. The circumstances though are very difficult for the both of them, and the people around them seem to exist only to make things worse. As nothing seems to go his way, Kinta eventually snaps.

Imamura uses the rather dramatic love story and the concept of raising pigs in order to present a number of sociopolitical comments regarding the era. The practices of the Yakuza and their connection with the American soldiers (who actually provided the main source of income for the destroyed Japanese economy, even through extreme practices, like the “renting” of daughters and girlfriends) have the lion's share in the commentary, with Imamura making a point of highlighting that they have turned the place into a pigsty, literally and metaphorically. This comment finds its apogee in the majestic ending scene, when swarms of pigs are released on the streets causing havoc, in a sequence that was largely responsible for the production going over budget.

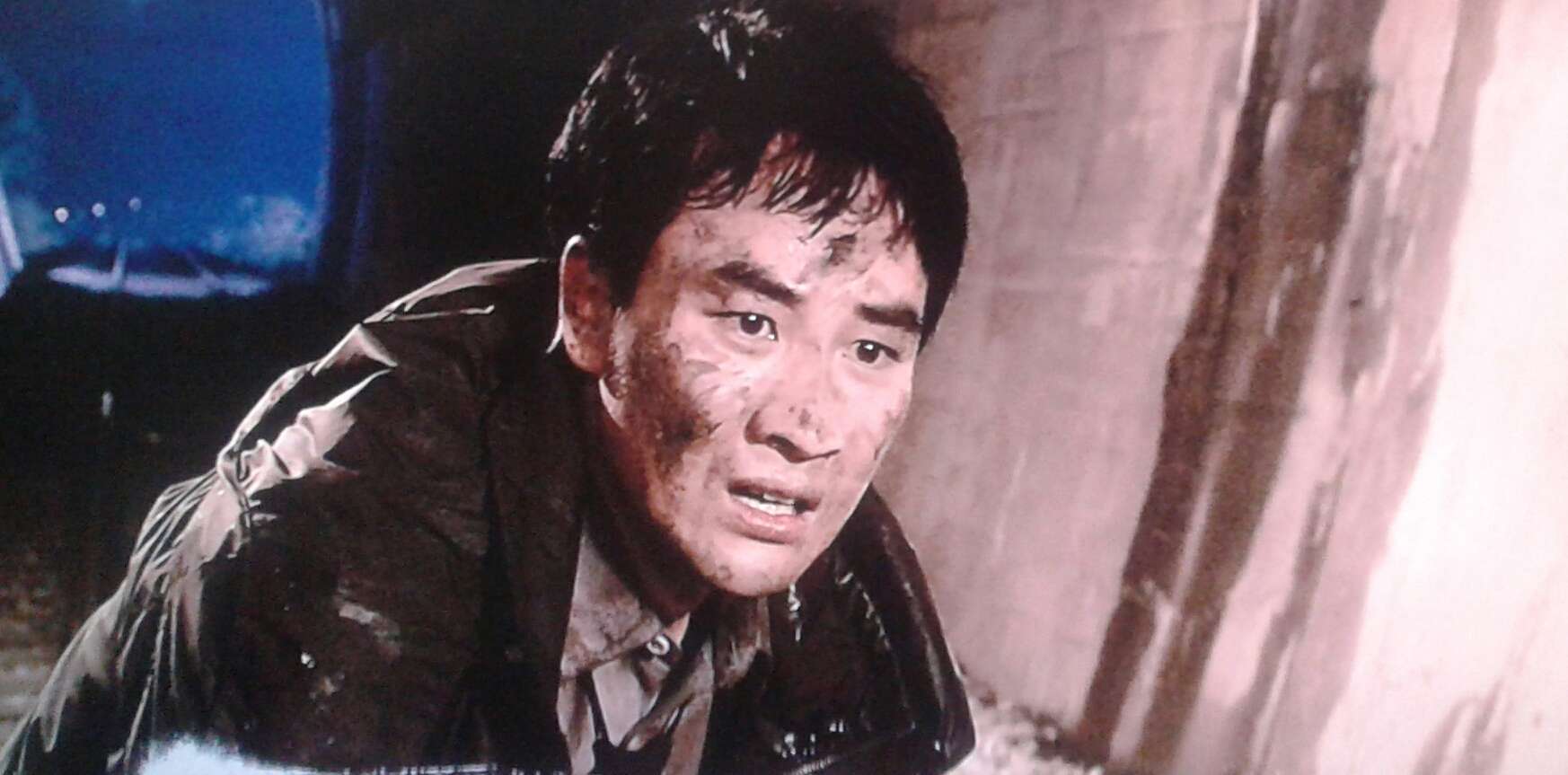

The fact the Japanese people of the era had no control of their fate whatsoever, is represented by Kinta (mostly) and Haruko (for the most part) who simply try to leave a normal life away from the violence and the exploitation, but continuously fail in the worst fashion, as both frequently fall victims to both. Imamura however, does not leave the film without a ray of hope, with the ending providing a rather optimistic closure to the story.

Imamura was in love with Kurosawa's “Drunken Angel” and particularly with Mifune's performance and that is how he instructed Hiroyuki Nagato to play the role of Kinta. His depiction of the absent-minded simpleton who keeps struggling against his limitations in caricature-like fashion is excellent. The one who steals the show, though, is Jitsuko Yoshimura as Haruko (in her first role ever) who presents a truly multileveled character who is at the same time sensitive, strong, pragmatist, ambitious, resilient and hopeless, with her performance, along the antithetical chemistry with Nagato, actually carrying the whole movie. The third pole in the acting department comes from Tetsuro Tanba, who is the main source of the black comedy aspect of the movie, as the hypochondriac “Slasher” Tetsuji, with Imamura making fun of every part of his supposed toughness every chance he gets. At the same time, however, his fate could be described as tragicomic, although the comic elements eventually wins, particularly in the finale.

On a last comment, Imamura also deals slightly with the Chinese and the Koreans' presence, with the first two being depicted as better off due to their inclination for commerce and the lack of traditional Japanese values, and the latter just with a comic note regarding their culinary tendencies.

Technically, the film is impressive, with Sinsaku Himeda's cinematography focusing on an amalgam of realism and impression. The dancing scene in the bar, the rotating shot in the rape scene, and most of all, the finale with the pigs are where the production values of the movie find their apogee.

Kurosawa's influence is quite obvious in “Pigs and Battleships”, but the road that eventually led first to the New Wave and then to international recognition, begun here, and that is where the true value of the film lies, along with the social comments and the plethora of truly memorable scenes.