There are plenty of lists throughout the internet about movies based on novels, but here in Asian Movie Pulse, we decided to compile a different one, a list that deals with movies that revolve around books (and authors, and bookstores etc) and not based on. The selection, as always, focuses on diversity but also on the quality of the titles included. Here are the best that we came up with, in random order

PS: I barely resisted the temptation of including “Throw Away Your Book, Rally on the Streets”, but the film has very little to do with books.

*By clicking on the titles, you can read the full reviews

1. The Great Passage (Yuya Ishii, 2013, Japan)

Yuya Ishii directs a genuinely Japanese film, in theme, style and pace, in the very difficult task of making the compiling of a dictionary into an entertaining movie. The fact that he succeeds in presenting a number of very interesting scenes in the world of vocabularies, which is filled with tabs and excel sheets, is his biggest accomplishment.

Inside the rapidly changing setting of the 90s, with the explosion of youth culture through video games, mobile phones and the Internet, Ishii manages to present the traditional Japanese values (patience, dedication, diligence, teamwork and the respect towards the elders) in the most appealing way. Like the compiling of a dictionary, the film flows slowly, patiently and the same applies to the characters' analysis and their relationships. Sentimentality is one of the key elements, but Ishii does not allow it to touch even the borders of the melodrama, as he manages to present the good and the bad of life and love without hypocritical dramatization, retaining a steady style throughout the duration of the film. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

Buy This Title

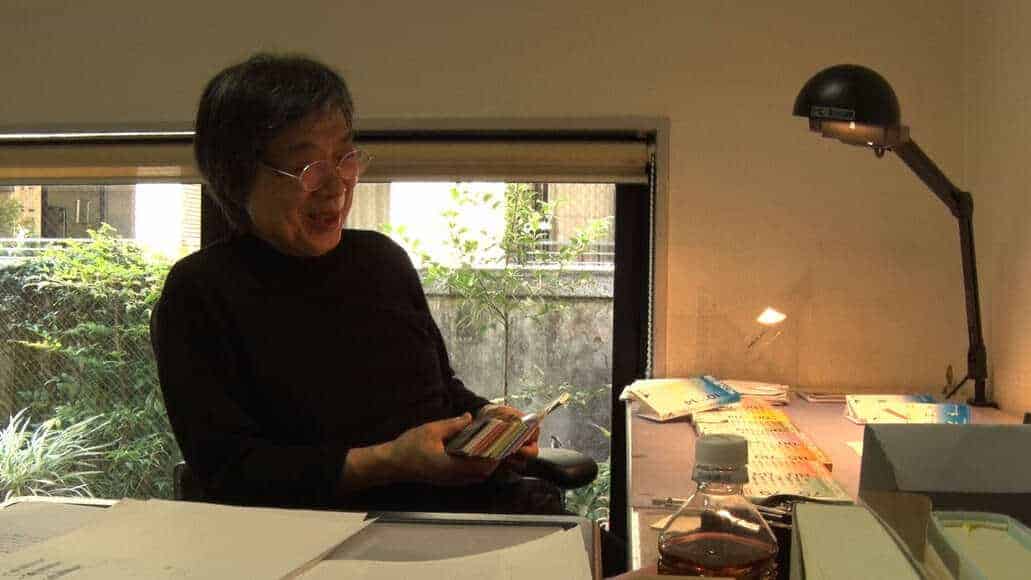

2. Book, Paper, Scissors (Hirose Nanako, 2019, Japan)

In that fashion, the movie presents his procedure, which starts with picking paper (the scene where his purpose of picking a particular paper is to mirror a woman's skin is impressive as much as indicative of his way of thinking), having it printed to check the quality, picking fonts and style, and still involves drawing with his pen, cutting with scissors, pasting with glue, and sometimes crumpling and straightening paper, with the help of his long-time assistant. Then, the outcome, through a rather interesting “slide-show” presentation of his works accompanied by jazz music, which made me think that his books definitely deserve a gallery exhibition.

Furthermore, through interviews with various members of the printing industry, Hirose presents the impact of his work, the way other people perceive him and his work, and the current situation of the industry. Subsequently, and in a rather dramatic element, the fact that what he is doing will soon be a part of the past, since the digital era seems to have no room for the attention to detail Kikuchi has shown all his life. Lastly, Kikuchi's own thoughts (how to be original after so many projects is a central question) about what he has accomplished (it is kind of funny that he perceives himself as a technician, not an artist) and about his retirement. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

3. A Tiger in Winter (Lee Kwang-kuk, 2017, S. Korea)

My synopsis is purposely filled with “un-“ words, as our hero seems to be temporary living in the negative dimension of his own life and the reason for it is a very fleshy and fierce one. The tiger in a series of popular Korean idioms and proverbs is a metaphor for our personal fears and demons. In this case, Gyeong-yu's fear of facing failure is paralysing him and keeping his life in a sort of nightmarish limbo and same for Yoo-jung, once an award-winner novelist (or was she?) and now dealing – barely – with a creative block and an evident sophomore anxiety.

It is interesting how this delicate character study slowly reverts the perception of the protagonists we gain at the beginning of the movie and gradually reveals a deeper truth. We learn that looser Gyeong-yu has actually written a novel in the past that is worth at least a bit of envy, while successful Yoo-jung probably wasn't even such a good writer in the first place. But Yoo-jung is too drunk too often to realise that the tiger is following her closely, while Gyeong-yu will eventually choose to face it and reset his priorities. (Adriana Rosati)

Watch This Title

4. My Dear Keum-hong (Kim Yoo-jin, 1995, S. Korea)

Kim Yoo-jin directs a kind of a biopic that has a realistic-dramatic base, but also includes many elements of sensualism, to the point that almost all sequences seem to end with Lee Sang having sex with a beautiful girl. Apart from that though, the story is quite interesting, particularly through the presentation of the differences of the two main characters, in an element that carries the film for the whole of its 96 minutes. Particularly the seriousness and the success that follow Bon-woong in every part of his life except for women and the flimsiness, almost constant laughing and the many failures in everything but women for Lee Sang form a rather entertaining base for the narrative. The fact that as the story progresses,, these differences expand is the main dramatic element of the story, particularly since Lee Sang seems to succumb into something very close to madness.

The third axis revolves around Keum-hong and the ripples she sends across the two men's lives, and particularly Lee Sang, who ends up with her, in a rather tragic relationship that becomes worse as time passes. Keum-hong in essence is the catalyst of the story, since their meeting shapes the path the two men eventually take significantly. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

5. Murder on D Street (Akio Jissoji, 1998, Japan)

The script of the film is a combination of two short stories by Edogawa Rampo, “Case of the Murder on D – Slope” and” The Psychological Test.” The owner of Suiko-Do, a bookstore, asks from Fukiya, a legendary art forger to make copies of paintings by Shundei Oe, an artist who painted portraits of women being tortured, and whose lines were considered impossible to be copied.

Using a trick, Fukiya manages to deliver, but the owner asks for more, this time without providing originals, but rather assigning a girl to him in order to use her as a model. A bit later, the owner is found dead and Saito, a clerk at the shop, is accused of her murder. After the police's initial investigation, legendary detective Kogoro Akechi appears at the police station to solve the case.

Akio Jissoji masterfully directs a sadomasochistic thriller that eventually becomes a game of cat and mouse. His depiction of the various tortures, the sex scenes, and the aesthetics of the Tokyo of the era is magnificent as it is cult, despite the film being somewhat “polished”. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

Buy This Title

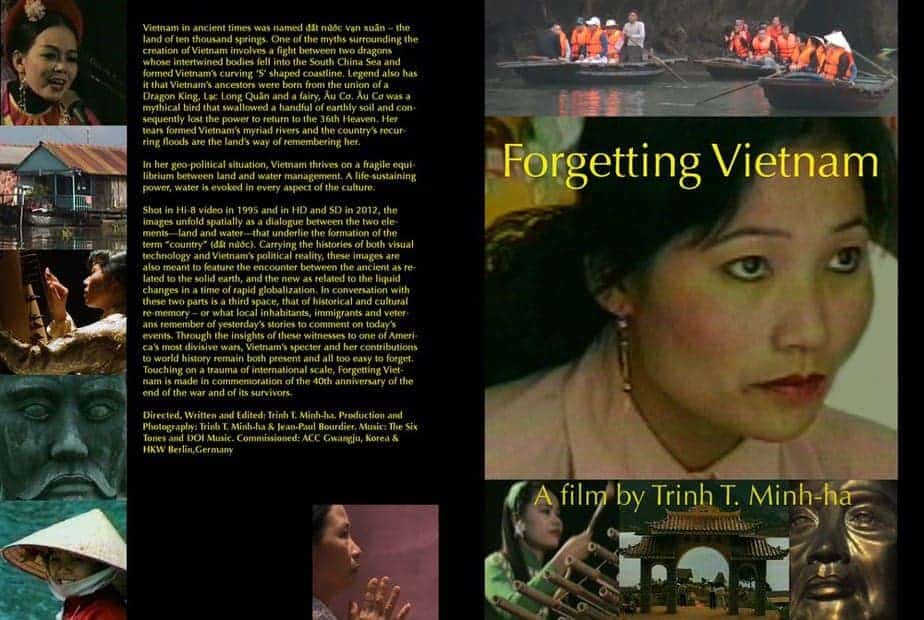

6. Manto (Nandita Das, 2018, India)

The look and feel of Das' film is enough for the viewer to be willingly swept away in its world, looking back wondrously at a time gone by, that was critical to our history as an independent nation, making the viewer consider the relation between art and life through Manto's life and five of his stories, which are evenly spread across the film's running time. It makes us consider the nature and circumstances of our independence, as in the words of the poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz, “jiska intezar tha, ye woh subah to nahi” (“This is not exactly the dawn we had waited for”). It is an endearing yet tragic film, endearing as the world knows and holds its protagonist in high regard, and tragic as it is about a proud and unparalleled artist whose life withers away due to his inner struggles and difficult social circumstances. (Vidit Sahewala)

Buy This Title

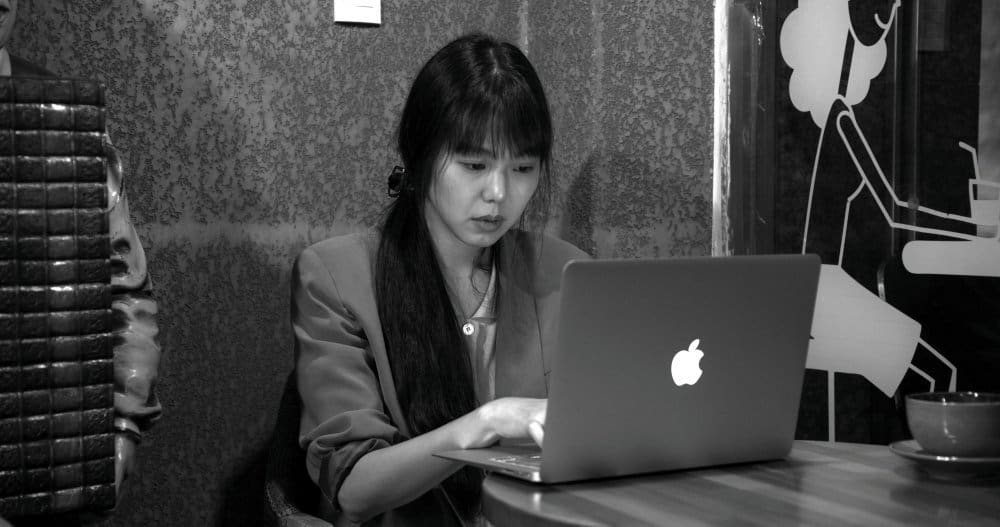

7. Grass (Hong Sang-soo, 2018, S. Korea)

It is not difficult to recognize Hong's handwriting in the series of two-way to three-way conversations, shot sometimes from the point of view that turns out to belong to Areum, and sometimes it substitutes for that of a third viewer – us. Yet, of course, it is not us who decide when and where to look, and for a while it is actually amusing to follow the lead. The whole film is built as a series of single takes of the conversations with intercuts being replaced by camera movements and re-focuses. In a way, it could be a little game of focalisation: do we watch the “real” conversations, or are these a result of Areum's notes and insights? The same way the choice of classical music to play alongside the talks, that would be a great fit for a wide lavish narrative or wild country, is in the end attributed to the coffee place owner's taste in music. (Anomalilly)

8. Dongju: Portrait of a Poet (Lee Joon-ik, 2015, S. Korea)

Lee Joon-ik directs a film that moves in two axes. The first one is in the present, when Yun Dong-ju is interrogated by the Japanese, regarding his and Song Mong-kyu's actions. The second axis unfolds in the past, as it describes the events that led to their arrest. In an elaborate practice, the two axes mirror each other, with the past one appearing according to the questions of the interrogation. Furthermore, Yun's poems, most of which are autobiographical, are also narrated according to the corresponding event appearing on screen. The synchronisation of all the above is one of the film's biggest traits and finds its apogee in a sequence during the end, where scenes of both Yun and Song alternate in magnificent fashion. Consequently, the editing is masterful, despite the difficulty the narration presented. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

Buy This Title

9. Poetry (Lee Chang-dong, 2009, S. Korea)

Lee Chang-dong uses the real-life case as a base but strays much away from it in order to focus on the life of the elderly in the country, and particularly the ones who live in the borders of society mainly because they have not secured a significant pension. In that fashion, we watch Mi-ja trying to survive on her own, almost without any help from the state or relatives for that matter, with the case of her grandson making her life even more difficult.

The generation gap is also presented, with her not being able to understand what her grandson is doing with his life and him treating her like a kind of a maid, with the sole exception of some games of badminton the two have. The first element is depicted quite thoroughly in a scene where Mi-ja is trying to use his computer ((Panos Kotzathanasis)

Buy This Title

10. Bakuman (Hitoshi One, 2015, Japan)

Teenagers, chained to a desk, frantically drawing, ignoring personal hygiene and feeding on instant noodles, in the hope of publishing their work in manga magazine “Shonen Jump”, is hardly material for an exciting action story. But Hitoshi One somehow succeeds with this good film-adaptation of popular manga “Bakuman”, which despite the two-hour duration, amuses and excites.

The film's dynamics and characters are the same that make Shonen stories compelling: high aspirations, friendship against adversities, success achieved through hard work and team spirit. The inevitable “meta-narrative” of a manga about two mangakas that create a manga (plus the fact that Bakuman's manga authors, are two, Takeshi Obata and Tsugumi Ohba) turns the movie into an intriguing matryoshka and Takeru Sato and Ryunosuke Kamiki are incredibly similar to their ink alter-egos. The addition of Lily Franky and some creative CGI effects complete the enjoyment and make “Bakuman” an adaptation with an extra gear and a fond tribute to a very peculiar aspect of Japanese popular culture, which, besides being one of the most important publishing sectors, has deep roots in the heart of a vast fan-base that goes beyond age and social status. (Adriana Rosati)

Buy This Title

11. The Long Excuse (Miwa Nishikawa, 2016, Japan)

Nishikawa places us in the confused emotional state of Sachio. The straight conversation with his wife is suddenly counteracted with a somewhat comical, upbeat tune accompanying him having sex with his mistress as his wife boards the bus, ending the beginning with silence as the bus weaves through the mountains on its fateful journey. The audience knows not what to expect of the next two hours, much as Sachio is unsure as to where his life will be in a year's time.

Nishikawa was a student of Hirokazu Koreeda, and his influence is clear to see in this film, with obvious comparisons to the odd coupling of “Like Father, Like Son”, a film which Nishikawa herself helped with the script. An obvious plot device to bring Sachio out of his indifferent state, Yoishi is everything that Sachio is not. Warm, likeable and expressing of his emotions, juxtaposed with Sachio's cold lack of action. While Sachio may state that his wife gave birth to his career, this seems to be the only role she played in his life – knowing little about her thoughts and ambitions. The fact that he never met the husband of her best friend until after the accident, shows how much attention to her life he paid. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

Buy This Title

12. Bitter Honey (Sogo Ishii, 2016, Japan)

Based on the novelist Muro Saisei's 1959 novel, “Bitter Honey” follows a poet named Ren Osugi, who is struggling with the concept of his impending death. The poet, who has a fondness for goldfish, finds the object of his interest coming to life in the form of an attractive female. At first complacent with her sheltered existence, the girl soon grows weary of her master and the restraints placed to keep her confined to his residence.

Sogo Ishii remains somewhat unknown in the west outside of his cyber-punk efforts, which is really a shame given the strengths of his other work. “Bitter Honey” acts as a meditation on insecurities when one is faced with his own mortality This is reflected in the romanticism of a creature we often associate with poor memory and short life span. The production is punctuated by some strong visuals and great performances from Ren Osugi and Fumi Nikaido. Its literary influences can be seen throughout the production through an engaging script that references its source material and its willingness to play with elements of fantasy.

The story includes another literary figure in Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, who committed suicide after a short, but influential literary career. This charter acts to further test Osugi's sanity as he struggles with the meaning his work can leave behind for those who will come after him. (Adam John Symchuk)

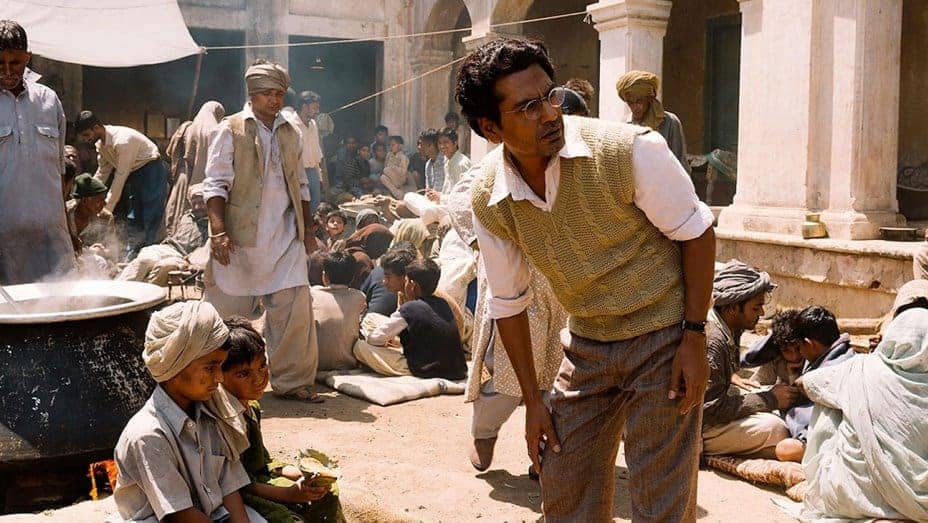

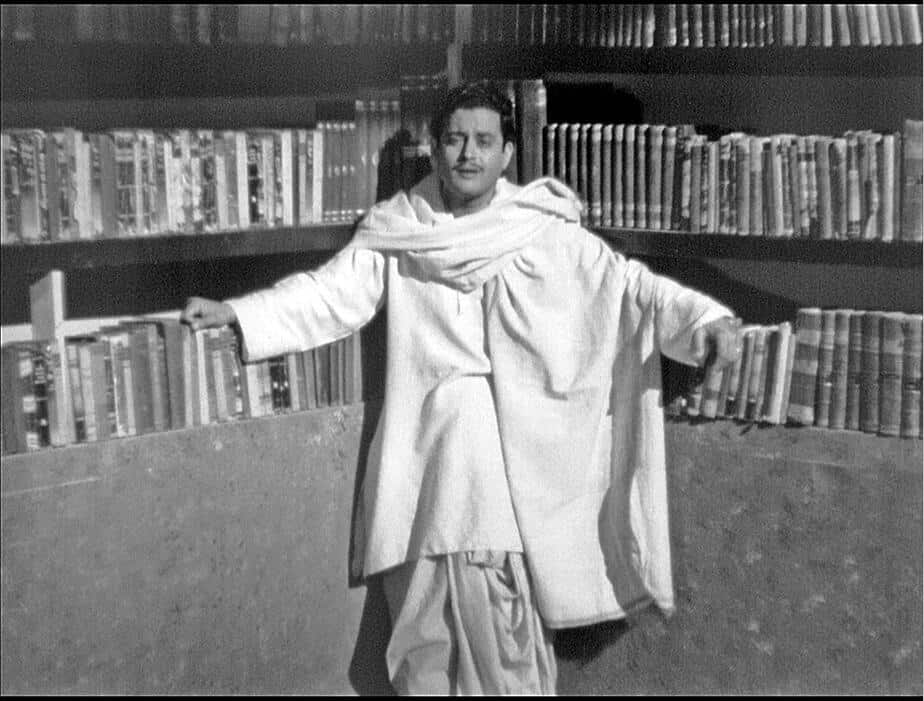

13. Pyaasa (Guru Dutt, 1957, India)

“Pyaasa” (1957), one of the finest Indian classics, deals not only with the literature itself, but also with the position of an artist in the society. The story revolves around Vijay, a poet, struggling to make ends meet. He impersonates the archetype of a neglected genius. Despite the talent and a unique sensitivity in perceiving the world around, he can't find a publisher for his works. The rejection reaches its peak when Vijay's brothers sell his manuscripts as wastepaper. Abandoned also by his ladylove, who decides to marry a wealthy publisher, the misunderstood poet finds a kindred spirit in the most unexpected of places. Another outcast, a street worker named Gulabo, becomes the sole admirer of his poetry, what is an ironic twist, sealing disenchantment with the world of materialism and corruption. The woman from margins of society is more humane and sensitive to art and its formosity than the educated elite. After an unfortunate incident, Vijay is thought to be dead. Gulabo manages to get his works published, and the old truth that death sells better is proven perfectly…

VK Murthy's cinematography is a poetry in itself. Profound use of darkness and light result in numerous breathtaking frames, still eagerly analyzed by film historians. Waheeda Rehman's (Gulabo) face has never looked as luminously stunning as when Murthy was shooting it. And last but not least, Sahir Ludhianvi songs in Urdu, the language of poetry, couldn't have been more fitting.

As we know now, Pyaasa drew poignant parallels between art and life. The main character mirrors the director Guru Dutt himself (who also played the role). Quite successful with his commercial films, he failed to attract the audience's attention with his magnum opus “Kagaaz Ke Phool,” what resulted in a personal crisis and suicide. Only after his death, Dutt's serious works were recognized and has gained a cult following. Vijay though, was partly built on the experiences of Sahir Ludhianvi, a lyricist and also a poet. (Joanna Konczak)

Buy This Title

14. Burning (Lee Chang-dong, 2018, S. Korea)

The paths of these three young souls cross and clash, releasing class frustration, male insecurity and a numbing sense of foreboding and premonition. Haunting and penetrating, this is a movie that gets under the skin like a parasite and plants its eggs of disquiet that will keep hatching for a long time.

If Murakami provides the skeleton of the story, there are few themes and threads that Lee Chang-dong takes from Faulkner's novel too and uses them to enrich the film's dense symbolism and Jong-su's character. Several sub-plots populate the story, one in particular about Jong-su's father who has an anger management problem and is jailed for it. Jong-su is desperate to escape his genes, just like Faulkner's Sartoris who must decide his own moral imperative. As both Jong-su and Sartoris are trapped in their social class, their status is embedded in their DNA. This encapsulates the deep fatalism of the movie that reveals itself more and more like a tale of absence; absence of Hae-mi and her ability to bend Jong-su's barren reality, absence of memories, absence of a cat (ok, for the joy of all Murakami's fans!) absence of inspiration for Jong-su's dream job as a writer and ultimately, absence of future. In the structural game of solids and voids, absence defines presence, like Hae-mi's imaginary orange. (Adriana Rosati)