During the 1960s and 1970s, the changes in the world with all its social and political upheavals as well as the general feeling of renewal (at least culturally) was reflected in the cinema of that time. While in the USA directors such as Arthur Penn, Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese made films which were about to change the face of Hollywood, as well as being satirical, sometimes dark comments on their times and Europe saw the rise of such filmmakers as Jean-Luc Godard, Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Francois Truffaut, in Japan the studio system was about to realize its state of stasis. With most of the big companies – Nikkatsu, Toei and Toho (just to name a few) – having to go through a time of economic difficulties and the strong competition from Hollywood movies, these studios had to react in order to stay relevant, not to lose the Japanese audience no longer attracted to their movies.

Buy This Title

The reaction of these studios to the changes of their times saw the rise or re-definition of such directors like Kinji Fukasaku, Seijun Suzuki, Nobuhiko Obayashi and Shunya Ito with works deeply rooted in Japanese movie traditions but re-inventing them in a way which was truly unique.

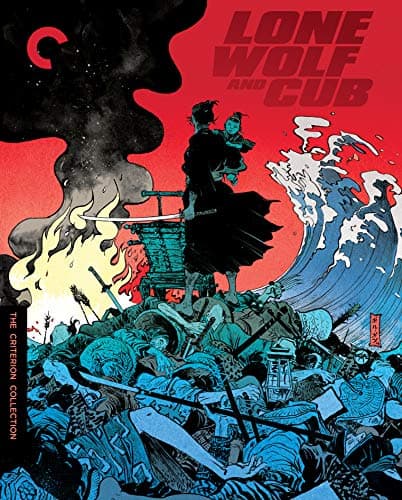

One of those works is the “Lone Wolf and Cub”-series with its first part, “Sword of Vengeance”, being released in 1972 and becoming a huge critical as well as commercial success. The films, which are based on a manga by Kazuo Koike, saw Tomisaboru Wakayama in the leading role of the former executioner of the Shogun Itto Ogami, a character which would define the fame of the actor, who, according to Patrick Macias, convinced writer Koike of his suitability for the part by meeting him in front of his home wielding a sword in front of him. Wakayama badly wanted to play the part, which has already been offered to him by his older brother Shintaro Katsu who was too busy starring in his other franchise, the Zatoichi-series. Wakayama, who was physically the exact opposite to the Itto Ogami in the manga, wanted to have the “blessing” of the creator of the character before he was ready to sign on for the role.

The movie is set during the Edo period in Japan, a time during which the Tokugawa shogunate ruled the country eradicating all traces of opposition and forcing every daimyo into either submission or to commit seppuku. Within the hierarchy of the shogunate. we have the Kurokawa-clan controlling the vast network of spies and the Yagyu-clan at the head of the assassins. The last branch of that hierarchy fell into the hands of the Ogami-clan, the position of the kaishakunin, the executioner of the shogunate.

After an elaborate scheme planned by the Yagyu-clan in order to control the position of executioner as well, Itto Ogami (Wakayama) is framed as a traitor plotting the assassination of the current shogun. As his wife and servants have been killed, Itto decides to walk the “Demon way of hell”, to take revenge for the injustice he experienced and finding work as a hired assassin from this moment on. His two-year-old son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) accompanies him having made the decision to walk side by side with his father, or rather sitting in the wooden cart Itto pushes through the fields, villages and forests their path leads them through.

During one of their stops at a temple, Itto and Daigoro are approached by a Chamberlain with the task of killing a rival as well as his gang of thugs currently stationed at a hot spring-village. Without hesitation, Itto accepts the offer making his way to the village which is completely in the hands of the gang outnumbering Ogami.

The Chamberlain is skeptical when his men bring him the news they have seen the infamous assassin, the “lone wolf and his cub” on the streets close to the temple they are currently in. Because the matter he wants to discuss is quite delicate and he wants to make sure that he will be talking to right person, he decides to test whether the person they have seen is the real Itto Ogami. Consequently, he commands his two bodyguards – two of his best swordsmen – to attempt to kill Ogami to prove of he is the real “lone wolf”. If he is, of course he will be victorious.

While the nature of his mission is quite dangerous and risky, the scene demonstrates nicely the abusive hierarchy within the various clans, families and houses the viewer sees in the film (and its various sequels). For the men in charge, such as the Chamberlain, soldiers and servants are mere cannon fodder or slaves they send into their deaths attacking a foe which either outnumbers them or is simply more skilled than they are. Hiding behind the code of the samurai, the bushido, men of power are repeatedly seen commanding their soldiers, scheming and plotting to achieve their aims, making the line between them and the gangsters Ogami will encounter rather blurry, to say the least.

Perhaps the film's best example of this principle is Retsudo Yagyu (Tokio Oki), the secret leader of the Yagyu clan controlling most of his clan's moves as well as the other branches of the shogunate. Since the last branch, the position of executioner, is occupied, he comes up with a scheme to make Itto Ogami, a man who has been loyal and following the bushido up to this point, appear like a traitor even sending one of his best men, Bizen, to kill Itto even though it is obvious his technique is far inferior to Ogami's, leading to his quick death. As Ogami attempts to chase after Yagyu, now that he has no more human shields to hide behind, the elderly man flees – in search for new soldiers and assassins. Consequently, Itto has distanced himself from the rules of bushido since being loyal does not mean one is protected or can expect the same from others.

In general, males in the film are either devious or downright savages, especially when given a position of power. Both, Yagyu or the head of the bandits Itto is sent to kill eventually, are downright despicable human beings, their existence and actions connected to death and misery for those around. If given the opportunity to exercise power these will result in violence, as can be seen in one scene during which several bandits overpower as well as rape a defenseless woman and kill the approaching father. Almost logically, women are mostly victims of these cruelties as their reputation and dignity can be easily taken away be brutes such as the bandits. Osen, the prostitute Itto and Daigoro meet in the village the bandits currently occupy, is one of those women refusing to be one of the hapless victims, one that is being made fun of by men who she calls cowardly as they cannot even defend their village from the attackers. In Ogami she finds an equal, an outsider in this society, but one who has “the wings to get out of here”, a skill which is denied her due to her gender. Her life, she says resignedly, will only be more miserable once she grows older.

From the moment he leaves his house, Itto and Daigoro are on the path of hell, as he claims, a journey defined by him being a sword for hire and a possible childhood for his son resulting in unhappiness and hardship. Even though it is more of a metaphor for their status from that moment on, given the images of misery, poverty, corruption and violence they witness on their way, Japan during this unspecified point within the Edo-era has become hell on earth. In one early scene, a woman embraces Daigoro as she mistakes him for his dead son, as her mother explains. Given that his son is for hire, Itto lets her hold Daigoro in her arms until she has finally calmed down; one of those rare acts of kindness in the film. Starting from this first installment of the series, poverty is shown as a cycle of exploitation and vulnerability, a sword which can strike at any moment, considering the obvious capriciousness and the wealth of the men in charge.

Itto Ogami, even though some of his scenes show a certain tenderness towards the victims of this system, is anything but a “Robin Hood”-figure even though he enjoys a certain appreciation among the people he meets due to his former glory as executioner, his skill as an assassin or his mastery of the suio-ryu technique. Tomisaburo Wakayama plays Ogami as a man with a certain stoic calm, as if he contemplates on the sights he sees or something which only he, and his son maybe, can see, because they have chosen a particular path to walk for the rest of their lives, or at least until they have had their revenge. Nevertheless, this sense of calmness is transferred to the almost meditative quality of the sword fights, especially the duels, in the film even further supported by their focus on singular sounds and movements. Ogami's duel with Bizen is one example in that matter and perhaps one of the best sword fights of the series, excellently choreographed and executed by the crew and cast.

In conclusion, “Lone Wolf and Cub: Sword of Vengeance” is a great first installment of the series, defining what will be valuable qualities for the movies as a whole, starting from the magnificent casting of Wakayama and Tomikawa as the eponymous Lone Wolf and Cub, the choreography of the sword fights as well as the portrayal of the time the movies are set. It is a brutal image of a period in time in which values and institutions have begun to rot reflecting a certain distrust of these aspects of society as a whole, a trend not uncommon in the 1960s and 1970s. Equal to the movies of Kinji Fukasaku and Shunya Ito, the series has done its part in deconstructing the classic role of males in Japanese cinema, especially the samurai and his code of honor exposing it as an excuse for powerful men to further exploit others and enrich themselves.

Sources:

Mes, Tom. “Vater, Sohn und Schwert: Die Lone-Wolf-and-Cub-Saga” (“Father, Son and Sword: The Lone Wolf and Cub-Saga”) (part of the German Bluray-release of the movies)

Macias, Patrick. “Samurai and Son: The Lone Wolf and Cub-Saga” (part of the Criterion-release of the movies)

“Lone Wolf and Cub: Sword of Vengeance” is screening at LEAFF