The delicate dance between fire and ice spins out of control in highly-anticipated animated film “Promare” (2019). Director Imaishi Hiroyuki (“Kill la Kill”, “Gurenn Lagann”) and well-beloved animation Studio Trigger (“Little Witch Academia”) have blessed the film with their characteristic low-frame, extravagant poses, sharply defined character designs, and of course — its self-indulgent giant mecha machines. While the film is sure to please loyal fans, “Promare” fails – at the same time – in truly creating something new, and instead falls back on a hackneyed script sadly telling of the film's low budget.

“Promare” is distributed by GKIDS in the United States, and Anime Limited in the UK. “Promare” opens in UK cinemas on 26th November (dubbed) with subbed screenings from 29th November

“Promare” begins with the Burnish, a mysterious race of people with a mutation to manipulate fire. Thirty years after they destroyed half of the world, the fictional city Promepolis buckles down on rounding up each and every Burnish under the claim that the Burnish as a race pose a threat to civilian safety. Not all the Burnish accept their fate so easily, however: extremist trio Mad Burnish swears to fight back to free their people once more. Leader Lio Fotia (Saotome Taichi) must butt heads with governmental obstacles, including boneheaded, but goodhearted firefighting newbie Galo Thymos (Matsuyama Kenichi) and tyrannical governor Kray Foresight (Masato Sakai). In a cat-and-mouse chase, the three fight mano a mano in an epic giant robot battle. As the war for justice wages on, the clock ticks down to volcanic apocalypse as the fiery souls of the Burnish threaten to ravage the world one last time.

“Promare”‘s implicit political metaphors provide an intriguing reflection of our times. The plight of the Burnish – of whom are literally picked off on the streets to be sampled on for scientific experimentation – disturbingly mirrors not just the ethnocentric genocide reminiscent of World War II, but more of the racial profiling oft-found in modern-day terrorism fears. Kray's persona takes an eerie Elon Musk-like attitude, as the mega-scientist-mogul plans a drastic escape plan in the form of a space ship utopia. The volcanoes are no exception to the film's extremely contemporary comment either: by placing the plot in a pressure cooker of climate-based destruction is hauntingly reminiscent of our own resignation to the natural world's impending doom.

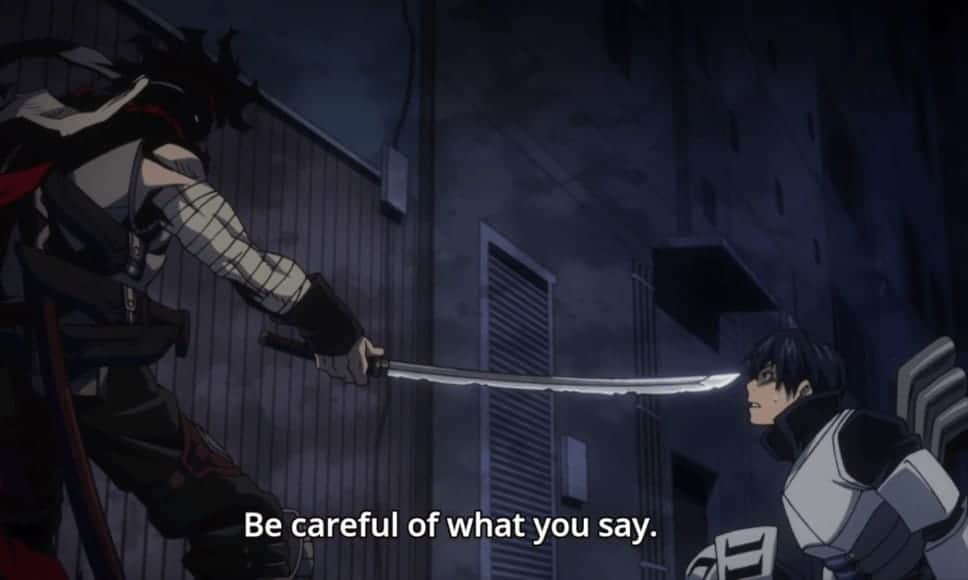

The messages get lost, however, by the visuals that make it so alluring. While Studio Trigger's dramatic sense of movement still remains incredibly articulate, the inclusion of new CGI studio Sanzigen regrettably commands more of the film's visuals. This is most evident in the fight scenes: as Imaishi tries to finesse the stripped-down CGI into an aesthetic choice — so that the pre-rendered models echo the geometric hand-drawn animation — they fail to settle naturally into the story. The mecha combat too drags out far too long too, and is almost fatiguing in their repetition. The bare bones CGI makes it abundantly clear: Imaishi had a painfully piecemeal budget to work off of, and tried to milk the most of it using the strengths of studios he worked with.

And unlike some reviews – GKIDS claims “Promare” the “spiritual successor” of Gurrenn Lagann – “Promare” smells more like a a corporate moneymaker than a passion project. Imaishi rehashes the same character designs, drawing parallels between Galo and Kamina, even going so far to insert another Boota reference with the firefighting rat Vinny. The script is so comically wrapped up in cliche that Matsuyama, as if bored of the lines, stretches Galo's voice with a Bunraku-like lilt to spice up the dialogue. “Promare” feels less of an original film than a distant echo of fan creation: instead of starting something anew, it merely feeds the flames of the fandom.

Despite the predictable twists and turns, “Promare” is still a thrilling watch. If not for the story, Studio Trigger's explosive animation and Yuaasa-esque color schemes are guaranteed to keep one at the edge of one's seat until the very end in sheer visual delight. It's just a shame Imaishi's handiwork is not more legible within the extensive use of CGI — but perhaps this simply is a marked turning point in the future of animated feature film.