Introduction

Bangladesh cinema industry activities are situated in the capital city of Dhaka. This industry generally produced Bengali language films of different styles such as melodrama, social drama, political action film, formula film as well as independent films. Bangladesh Film Development Corporation (BFDC) has played a center point of supporting and supplying raw materials in filmmaking. In 1898, people of this land first experienced moving images on the screen by the arrangement of a company named Bradford Bioscope Company; though it was limited to elite class audience. This region started producing movies with the short film “The Good Girl” (aka Shukumari, 1928) in silent era (Hayat 1987). Within three years, Bangladesh experienced “The Last Kiss” (1931), its first feature length film. Both films were patronized by the royal family the Nawab Family (Hayat 1987). They formed a production company eventually in the 1930s titled as Dhaka East Bengal Cinematograph Society to produce films regularly.

Nevertheless, the practice of making films started in Bangladesh (the then East Bengal) in 1900, when Bangladesh was part of undivided India. Hiralal Sen (1866–1917) was the pioneer of filmmaking in Bangladesh. He was the first person who launched a film company named The Royal Bioscope Company to show films in public sphere (Raju 2014). He later became a film distributor as well. His first production titled “Sitaram” was a recorded version of a theater play. In his twelve years career, he made more than twenty films including feature length fiction and documentary (Asgar 1993).

In 1947, the British colonial ruler attached Bangladesh with Pakistan as East Pakistan, based on Muslim majorities during the partition (Chatterji 1994). At that time, approximately eighty cinema halls were running through Bangladesh but numbers of local films were not many (Chakrabarti & Chakrabarti 2013). People watched Indian, Pakistani Urdu and American films. Dhaka became the new center of modern art, literature and thoughts in the subcontinent after the partition. It took ten years to start making their films. From 1970s to 1990s was the most successful and memorable era of Bangladesh cinema. In current time, popularity of local cinema and number of cinema halls are gradually decreasing.

From 2000 onward, local alternative/independent filmmakers started getting accolades from international festivals and TV channels stepped forward to invest in films that were made outside the BFDC; although cinema-goers number did not increase to a significant number.

History of Production

“The Face and the Mask” (aka Mukh o Mukhosh, 1956) was the first locally produced film with sound, although post-production of it was done in Lahore, (West) Pakistan (Waheed 2005). At that time, post production facilities were not available here. This attempt opened up a path of locally bred stories and filmmaking practices in Bangladesh. Iqbal Films was the producer of this film (Waheed 2005). In 1957, East Pakistan Film Development Corporation (now Bangladesh Film Development Corporation) was established in Dhaka by the central government with studio and post production support (Bangladesh Film Development Corporation 2017). From 1959, it started to run full-fledged. From 1960 to 1971, Bangladesh experienced more than 100 locally produced films. All films were produced by local producers and made by local craftsmen. Most of the films were in black and white, colour films were also there but due to excessive expense it was not the first choice of the producers. The story of these films ranged from romanticism of rural life, to life of river-bound land, to fantasy, to urban satire, to social examination of 1947 India-Pakistan partition, to political justice, and self rights (Hoek 2014).

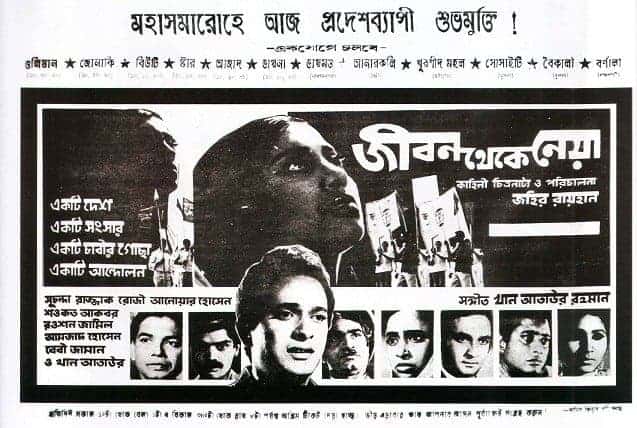

During this time, film became a tool of protest against the autocratic, oppressive military regime of West Pakistan (Raju 2014). Especially in 1970, the makers were too active with audio-visual media to portray the oppression of the ruling class. Zahir Raihan made one of the most significant films, “Taken from Life” (aka Jibon Theke Neya, 1970) that had a huge impact on public to stand against state oppression. The then censor authority tried to lock down the movie but they failed due to public demand (Rasmussen 2010).

Besides East Pakistan Film Development Corporation, local investors came forward to establish film studios around Dhaka city. Three studios were established in the 1960s – Bengal Studio, Popular Studio and Bari Studio with post-production and shooting facilities (Hayat 1987). It signifies how vibrant the filmmaking scenario was at that moment.

After being liberated from (West) Pakistan through a bloody war in 1971, filmmakers dreamt of a new day. In mid-1970s, the government took some positive steps towards the industry such as establishing national film awards and financial grants for creative film projects (Kabir 1979).

Liberation war became an inevitable topic for filmmakers in the post-independence period. They offered original and thought provoking stories through the 1970s.

In the 1980s, the audience experienced the rise of commercially and critically acclaimed films as well as stardom, popular cultural fever and tendency of plagiarism of Bombay films. To counter this phenomena, a bunch of wild young men stepped into the filmmaking business to make and promote alternative and independent cinema in Bangladesh. They brought back the naturalism and realistic view on the screen and they tried hard to establish the alternative film distribution circuit in Bangladesh (Raju 2014).

The 1990s were the age of falling from grace for Bangladesh film. For the sake of money, commercial filmmakers opted the way of copying Indian Hindi films which were full of fighting, songs, dance, and unnecessary jokes. These films were neither B-grade films nor well made, but they were strangled in between those. Eventually the audience turned their back to the cinema hall and the business loss went deep to deeper (Hoek 2014).

From the mid-2000s, the number of TV drama producers, directors, and professionals started to venture in film and the viewership started to rise again in urban localities. Films like “Monpura” (2009) played a big role into bringing back urban middle class viewers to cinema halls (Kabir 2009).

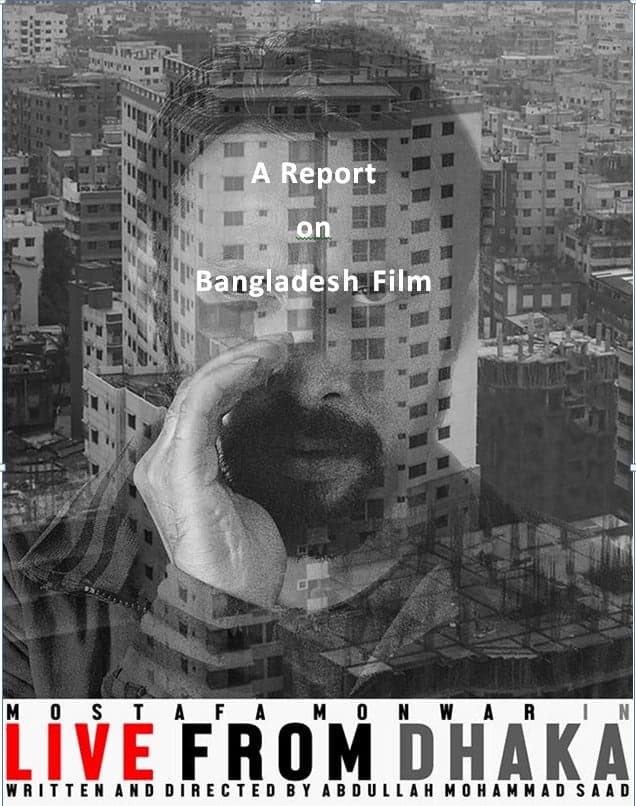

Along with this reality, Bangladesh film went and got critical appreciation from international film festivals such as Zahir Raihan's “Stop Genocide” (1971) awarded in Tashkent Film Festival in 1972. Sheikh Niamat Ali and Moshiuddin Shaker's “Surjo Dighal Bari” (1979) was awarded in Mannheim Film Festival. Tareque Masud's “The Clay Bird” (aka Matir Moyna, 2002) clinched FIPRESCI award at the Cannes Film Festival in 2002. In recent times. Kamar Ahmad Simon's “Are You Listening!” (aka Shunte Ki Pao!, 2012) got Grand Prix for Best Feature-Length Documentary in the 35th Cinéma du Réel 2013, France; Mostofa Sarwar Farooki's “No Bed of Roses” (aka Doob, 2017) got selected for Busan International Film Festival 2017; Rubaiyat Hossain's “Under Construction” (2015) was appreciated in 69th Locarno International Film Festival 2016 and Abdullah Mohammad Saad's “Live from Dhaka” (2016) got selected in Bright Future category in International Film Festival Rotterdam 2017.

System of Distribution and Exhibition

Bangladesh cinema has a complex type of film distribution and exhibition system. Distributors and exhibitors, in most of the cases, take a large amount of the revenue. To avoid this situation, producers have now become distributors to distribute their films and keep the margin in their account. In recent years, Moonsoon Films, Jazz Multimedia and Tiger Films have become the successors of this practice. With the changing scenario, the projection system is also changing from reel projection to digital projection. In this distribution and exhibition system, exhibitors play a definitive role, here exhibitor signifies the owner of cinema halls. The exhibitors collect films from the producer-distributor end to run them in their theater. Producers and distributors actually rent the copy of their film to the exhibitor and it happens in three different ways:

- Minimum Guarantee (MG) means exhibitor must pay minimum guarantee money to the distributor which is non-refundable. The amount varies from 1,834 USD to 3,669 USD for a well-doing film

- Percentage indicates as an alternative to MG money, the exhibitor will share the profit and will collect the print of the film by repayable advance money (which is flexible too). Cinema Hall owners of Dhaka and around use this process

- Fixed Rental implies that the exhibitor will get the print of a film by giving a fixed amount of money at a time and run the film at his own risk. Whether it manages profit or loss the distributor will not be affected by that. So, if the exhibitor gains, he will not have to share the profit with the distributor

In between distributor and exhibitor, one character plays a crucial role and that is the booking agent. Booking agents cut profit from both the distributor and the exhibitor, they are third party entities who work as a communicator between exhibitor and distributor. In most of the cases, the exhibitors who have a hall in a remote place from the city get trapped in the booking agent trap. Booking agents are the unavoidable existence in film business in Bangladesh (Mahmood 2013).

The exhibitors actually are never satisfied with the rental money that they need to pay to obtain films. On the other hand, producers and distributors always complain about the manipulations of the booking agents and blame the exhibitors for patronizing them. Nevertheless, many film personalities believe that with the introduction of Digital Film Projection and other innovative technologies, this conflict will trim down gradually.

Conclusion

In Bangladesh (the then East Pakistan) local filmmakers made and produced Bengali language films as well as Urdu language films and competed with Indian and American films in the theater during 1957 to 1971. Day by day local films got more popularity than the other films and the infrastructure, skilled technicians, producers and cinema theater numbers were getting bigger. After 1971, some things were not changed as expected in the newly born state, such as the embargo on Indian and international films, or authoritarian censor board. In the monolithic market, the filmmakers started to make formula films or copied from Indian films, resulting to the audience losing interest in mainstream or commercial cinema, cinema halls getting shut down, and emergence of piracy and the absence of tight anti-piracy law. All of these things made the situation even more adverse for filmmakers. Subsequently, by the presence of VHS tape player, later CD/DVD player, satellite TV, and World Wide Web, the local audience got a chance to choose from options rather than going to the cinema hall and being bound to watch the same story with different faces and places.

Alternative and independent filmmakers' productions brought some changes but they did not make a big remark on the taste of mass culture. Their cinema fed a portion of mass people known as urban, but their cinemas remained unreachable to the rural audience. It was not only their responsibility that those movies were not reaching the rural areas but also the liability of the nexus of distributor-exhibitor-booking agent.

Gradually, alternative and independent filmmakers' productions began to get accolades and appreciation from international festivals and media bazaars. By the number of population, Bangladesh is an interesting and lucrative market for screen business, but what it needs is a flexible, tangible, business-friendly film policy, along with strong infrastructure and skilled, trained, professional people.

Reference List

Asgar, S. 1993. Hiralal Sen, Bangla Academy, Dhaka.

Bangladesh Film Development Corporation 2017, History of Establishment, viewed on 20 September 2017, <http://fdc.portal.gov.bd/site/page/e53a7e72-4d4d-4fbc-8bc5-032ddb7c58d8>

Chakrabarti, K. & Chakrabarti, S. 2013. Historical Dictionary of the Bengalis, 1st edn, Scarecrow Press, Maryland.

Chatterji, J. 2002. Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932-1947, 1st edn, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Hayat, A. 1987.BangladesherChalochitrerEtihash (A history of Bangladesh cinema), 1st edn, Bangladesh film Development Corporation, Dhaka.

Hoek, L. 2014. Cut-Pieces: Celluloid Obscenity and Popular Cinema in Bangladesh, 1st edn, Columbia University Press, New York.

Kabir, A. 1979.Films in Bangladesh, 1st edn, Bangla Academy, Dhaka.

Kabir, J. 2009. ‘A Heartwarming Film', The Daily Star, March 2009, viewed 20 September 2017, <http://www.thedailystar.net/magazine/2009/03/04/film.htm>

Mahmood, S.M.K. 2013.‘Film Distribution in Bangladesh: Big-Screen Today and Tomorrow', Masters Thesis, Independent University, Bangladesh, Dhaka.

Raju, Z. H. 2014. Bangladesh Cinema and National Identity: In Search of the Modern?, 1st edn, Taylor & Francis Ltd, London.

Rasmussen, D. 2101. Welcome to Dhallywood: Cinema of Bangladesh, 1st edn, BiblioBazaar, South Carolina.

Waheed, K. 2005. Celebrating 50 years of our cinema: Remembering Mukh O Mukhosh and Abdul Jabbar Khan, 12 August 2005, viewed on 19 September 2017, <http://archive.thedailystar.net/2005/08/12/d50812140197.htm>

Imran Firdaus is a film researcher, educator, curator and video artist. He established, curate and programmed International Inter-University Short Film Festival organized by Dhaka University Film Society from 2007-2011. His video arts exhibited several places including Slade school of Fine Arts, London. Currently he is perusing Masters in Media Arts and Production at University of Technology, Sydney. His latest venture Prodorshonii- instagram based art exhibition site. He can be reached at [email protected]