By Wally Adams

In immediate postwar Seoul — a crime haven run by the black market when South Korea was one of the poorest countries in the world — Yeong-sik (Kim Hak-a) leads a gang of down-on-their-luck Korean male ruffians alongside female streetwalkers. They include his brash girlfriend/“business” partner So-nya (Choi Eun-hee) and her more soft-spoken associate Julie (Kang Sun-hee). As most of them scour around an American military base, the prostitutes serve the dual purpose of making money from serving the soldiers and sometimes also distracting them in order for Yeong-sik's men to pull jobs stealing military goods to sell on the black market.

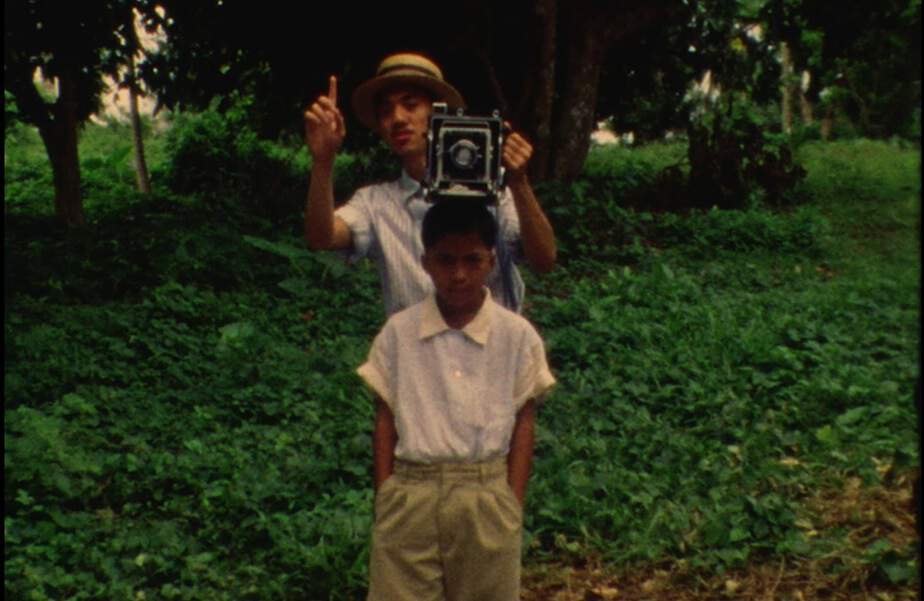

“The Flower in Hell” is screening at London Korean Film Festival

But then his bumpkin brother Dong-sik (Cho Hae-won) arrives there from the countryside after completing military service to take his brother back to care for their mother. Yeong-sik's strong resistance not only to the idea of leaving his lucrative business but to going back with his army veteran brother who he “can't show his face in front of” makes Dong-sik even more determined to try to bring him back on the proper path.

Nevertheless, Dong-sik comes to understand his brother's position better as he finds himself faced with strong temptations of his own, trapped in-between familial loyalties towards his criminal brother, lustful desires towards So-nya (whose name can be easily transliterated into “Sonia”) and a perhaps more pure but (by society and his own values) forbidden bond with Julie.

To this day, Shin Sang-ok is one of the most important and prolific directors in Korean history, having made more than 70 films. He also had without doubt the most interesting, wildest and strangest career of any Korean director (or from most anywhere else) that also widely corresponded with many major turns of Korean history, society and politics.

He presided (as assistant director) over the very first postcolonial Korean film “Viva Freedom” in 1946 and was one of or the most successful directors of South Korea throughout the 1950s and 60s. Several of his films, including “The Flower in Hell” starred Choi, who was by then his wife and one of the country's top actresses. But right as he was at his most fruitful period, things went on a major downward spiral starting with (in the first of many parallels between his life and his films) his scandalous affair that continued with a divorce and Choi's disappearance. The rest would be no fault of his own. First, the industry in general suffered a severe slump in the 1970s where very few directors including Shin were successful and all had to fight hard battles against government censorship and….TV. The growing power of both, severely ravaged the industry. Then dictator Park Chung-hee personally reprimanded him, revoked his filmmaking license and forcibly shut his studio down.

Just when it seemed things couldn't possibly get any worse (or weirder) from there, his life had genuinely become a movie itself during a trip to Hong Kong searching for his ex-wife (who some suspected he murdered). There he found out exactly what he wanted to know by being kidnapped by secret agents under orders of North Korean Motion Picture & Arts Director Kim Jong-il (16 years before he would inherit his father's position as Supreme Leader). He would spend nearly a decade in the DPRK that included undergoing years of re-education in a labor camp, a surreal re-marriage to his ex-wife (who it turned out was abducted before him) presided over by Kim, and being forced to make 17 propaganda films including the pseudo-Godzilla-style “Pulgasari” . Then the couple managed to escape to the USA, where they would become double-refugees from both Koreas (and where Shin would work on the shamelessly fluffy children's martial arts “Three Ninjas” series) before finally returning to South Korea.

But “The Flower in Hell” was made during Shin's creative peak when his films tended to have their foundation in harsh reality before being driven to do a variety of ludicrous films outside his element in three countries. Rather similar to Italian neorealism in its themes and frank dialogue if not so much its presentation (not shying away from fitting in a couple of fist and gunfights), “FiH” creates a believable world of the seedy urban fringes and outsiders of society, showing real merchants, soldiers, dancers etc. to a commendable extent. It also shows a remarkable degree of sympathy towards sex workers years before it became anything close to the norm in South Korean cinema (which by the 1970s was inundated with prostitute/hostess melodramas). That was in all likelihood influenced by Shin's own experiences living with a prostitute (for reasons of convenience — not THAT kind) during the Korean War, as most others opted to avoid them even with the alternative of crowded living quarters. So he looks at the world's oldest profession and other kinds of sex work in unusually neutral terms, not condoning it at all but making it just as much a point not to demonize women for ending up there.

And in that neutrality, the filmmakers weren't above wanting to show off the allure of such work, as when lingering the camera on a Korean exotic dancer performing for American soldiers (with quite graphic gyrations that most of the world's film industries would not have tolerated in 1958). But while the film is conceptually rooted in realism, some of the storytelling is certainly not.

I'm driven to think that the character motivations and behavior can be implausibly irrational. Perhaps some of that was a reflection of Korean society's own hypocrisies at the time, but that dimension isn't clearly challenged. Interestingly for example, Yeong-sik has a far, far bigger problem with even the idea of So-nya having any kind of intimate contact with his men or brother despite having much less problem with the fact she's open to random American soldiers every day (but if he can make money off of it, it's then a noble sacrifice I suppose).

But more incredulously, while the film and Choi's edgy performance do make So-nya's character a very effective vamp who complacently wonders “doesn't this solve everything?” (take a guess what “this” is), the movie is clearly judging her for being a prostitute and overall vixen while also being someone's girlfriend a lot more than it is the boyfriend who is actually directing her in prostitution. She's also unnaturally stupid and apparently completely unable to even consider what anyone else's reaction might be to her siren schemes and whims.

Granted, it's a sad truth there really are men who are that hypocritical in their values and women who are that stupid, but especially after she already sees firsthand how the brothers regard each other and talk to each other, her actions approaching the end seem dense a little beyond plausibility, especially when noting how crafty she could be otherwise. Even so, this movie is remarkably sordid and immoral (in its characters) for the 1950s, with every single main and supporting character besides Dong-sik in one or more criminal/immoral trade and even Dong-sik far from a pure hero and fairly easily given to reckless decisions himself. Tellingly in fact, the character that emerges the closest to pure and noble of anyone (or deserving of the title's namesake despite having a lesser role) is prostitute Julie.

On that note, the film's sharpest dialogue takes place between Dong-sik and Julie, as she wonders in quite down-to-earth fashion what real future she could have in a society that regards her and those like her as it does. “Why wouldn't someone marry you? You're smart and kind”, Dong-sik reassures. So Julie simply follows up by calling his bluff of courtesy, asking if he would (even hypothetically) marry her then. Cue predictable silence. “See?”, she responds in too-cynical-to-be-disappointed tone. Candid but composed explorations on how Korean society often unfairly viewed/views perceived deviants or products of deviant behavior was a recurring theme in Shin's films, and this scene was probably one of his most trenchant of all.

Also, Shin's ingenuity as a director shines most during the climax, with a character trudging through the mud and fog playing out almost as much like a horror movie with touches of film noir as it does a Korean melodrama — the latter tendency which is surprisingly held back until the end. That scene culminates with one of the iconically striking shots in Korean cinema.

So despite the rather questionable buildup in places, “The Flower in Hell” is potent and mostly progressive early South Korean cinema that manages respectably level-headed examination of the society's outcasts. Furthermore, it serves as a fascinating progenitor of the genre-meshing trends that the industry would become known for worldwide today.

“Americans, Koreans, they're all the same. Money is all that matters. Money's the best.”