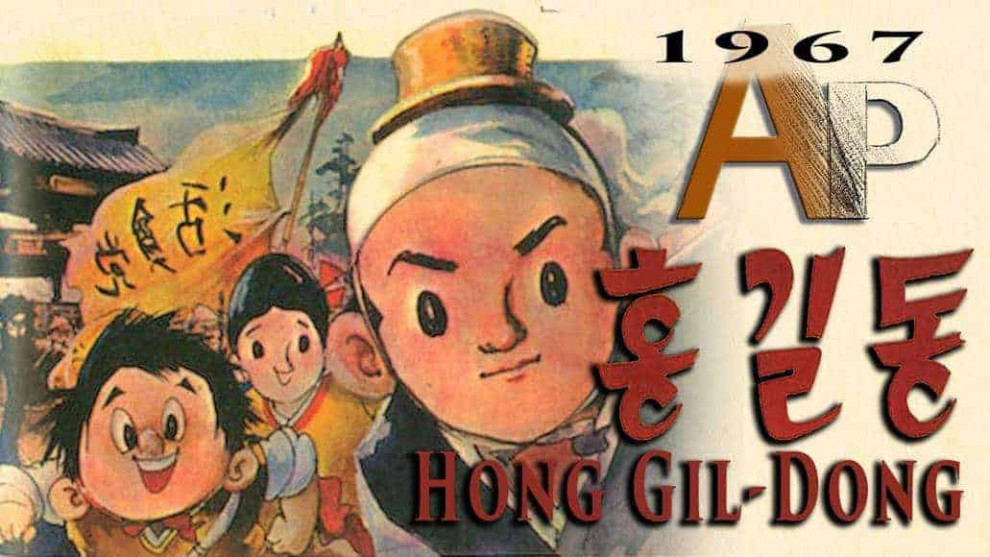

With little to no prior training, a home-made multiplanar camera, and perpetual resource scarcity, Shin Dong-hun managed to complete the impossible: he directed Korea's first feature-length animated film. Uniquely Korean in character, but ubiquitously critical of class structure, 1967 film “The Story of Hong Gil-dong” follows folk hero Hong Gil-dong's quest to right society's wrongs. In over 125,000 cels barely spilling over one hour, Hong must endure dancing skeletons, intense training, and even a dragon to overcome the common enemy: the power-hungry civil officer who over-taxes his locale for his own gain.

The Robin Hood-like tale reportedly originates to Heo Gyun, a radical intellectual from around late 16th to early 17th century Korea. In the 1960s, director Shin's brother Shin Dong-woo adapted the folktale into a comic-strip, of which Shin Dong-hun has worked from himself. His characterization of Hong Gil-dong follows that of the strip. Hong Gil-dong is the attractive, yet illegitimate son of a nobleman and lowly concubine. He is rarely seen alone however; teamed up with miniature partner Chadol Bawi, the two regularly tease the rich who exploit the poor. When the entire village gets punished for Hong Gil-dong's latest stunt, however, the duo decide to draw the line. They set out to master the art of sword-fighting under a mysterious spirit-teacher, eventually rounding up their own army to properly finish off the corrupt magistrate once and for all.

In retrospect, Shin's animated film is a delight to watch. Befitting of a national first, “The Story of Hong Gil-dong” makes sure to emphasize its origins to the last degree. The hand-painted backgrounds evoke watercolor paintings of Joseon-era architecture, nostalgic of the past. The neutral color design of muted yellows – likely a side-effect of the virtually non-existent budget that Shin had to work with – especially allows the carmine reds of the rich and the magistrates to pop, as they would have with traditional costume dyes.

While Shin's backdrop maintains its nationalistic Korean-ness, he does not shy away from borrowing the visual language of American television. Indeed, Shin's mastery of movement emulates that of “Tom and Jerry” production studio Hanna-Barbera. Unlike Disney's full-animated characters, Shin's characters do not nimbly waltz from one frame to the next; instead, they start and stutter in their low frame-rate, moving for the sake of narrative rather than to imitate life. Chadol Bawi huffs and puffs just as Tom would, and stars fly everywhere when characters throw themselves into a brawl. For as much as Shin's film is Korean in a folkloric detail, its animation is indisputably American-influenced. Perhaps this just makes Shin's film all the more contextually Korean: it is clearly influenced by the media introduced by post-Korean War American military occupation.

And while the animation itself is not entirely uniform, it is still a pleasure to watch. As Shin mentions, almost everyone in his studio (including himself!) was fairly new to animation; hence, the animators would often improvise their own understanding of movement. In one scene, Chadol Bawi may “run” in two-step, barely making progress across the frame as his legs frantically move. In another, Hong Gil-dong may make astronomical leaps across an entire mountainscape, as if he were jerked around on a live-wire. While some commentators may note the animation odd, the film's idiosyncratic rhythm remains an apt reminder of monetary and material scarcity Shin's studio had to work with.

Hong Gil-dong's legacy – reincarnated in various forms of literature and media for the last five centuries – still remains a timeless classic five decades after his animated debut. Shin's film remains incredibly self-aware of its importance in the history of Korean cinema, strictly sticking to its Korean origins in story, visuals, and even in its ragtag cadence. Its programming slot is only well-deserved within the London Korean Film Festival‘s celebration of 100 Years of Korean Cinema.