Kazakh director Emir Baigazin emerged in 2012 with “Harmony Lessons”, which won Berlinale World Cinema Fund and the Silver Bear for the best cinematography. He impressed the audiences with his unhurriedly poetic, yet dark and cruel tale about entering the adolescence and the interconnections of power and violence. These themes resonated also in “The Wounded Angel”. With „Ozen” (“The River”), which premiered at Venice, the director concludes his informal trilogy of Aslan. All its parts included the character sharing this name, although it is not the same boy, just the figure used by Baigazin to introspect the coming-of-age tensions and the symbolic end of childhood. In the third movie, however, the director opted for a lighter tone than in the previous installments.

“The River” is screening at Across Asia Film Festival

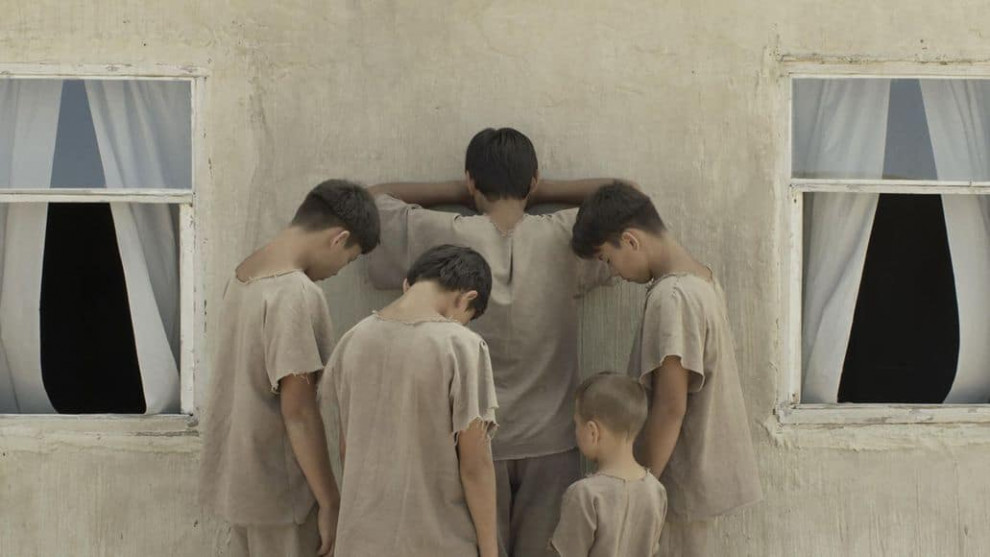

Aslan from “The River”, played with engrossing maturity by Zhalgas Klanov, is the eldest of five brothers. The siblings live with their parents, severe and emotionally frigid father (Kuandyk Kystykbayev) and submissive, almost transparent mother, somewhere among the endless hills and plains of dusty sun-burned soil. The area is a remote space of isolation, where humans, despite their respect for nature's might, seem to be just unwanted guests, cunningly snatching away what lays within their grasp. Initially, there are no clues whether the story is happening at a certain point of time, it could as well be at present and decades ago, in Kazakhstan or someplace else. The area almost seems a parallel universe, where life proceeds in a constant and invariable cycle, far from the benefits and enticements of civilization.

Aslan's responsibility is to orchestrate the boys in the rhythm of daily chores and farm works, so he delegates tasks ranging from watering the garden, looking after livestock or baking bread, to making bricks of mud and leaving them to dry in the sun. He is also a patient reading teacher as well as an attentive guardian and protector, arranging games and plays for his brothers. Father delegated him to do so, giving him this share of his paternal power. The sterile and surreal microcosm of the family's enclosure brings to mind Lanthimos' “Dogtooth”.

Father's ways are strict, as he expects obedience and discipline, ready to punish the boys with beating whenever they dissatisfy him. Aslan, whose name means “lion”, on the contrary, has a different approach. His relation with other siblings is filled with compassion and humanity he sympathizes with their errors and mischief and tries to defend them from patriarch's anger. However, despite his shield of empathy and fairness, the boys feel enraged by the monotony and harshness of their duties. One day, Aslan starts taking them to the river, about which he speaks profoundly in the very first scene of the movie. The visits have τηε charm of the forbidden fruit, combinινγ a mystery with an act of revolt. The river becomes the mystical space of undisturbed play, where children express freely, feeling the bliss of liberty and self-determination. Immersing in shiny-silver waters, they reach inner peace. This new ritual changes them, as the boys, having found their secret getaway, seem more diligent in their daily burdens. Their life is immersed in peace and harmony again.

When the first crisis seems to be averted, an unexpected visitor arrives, turning the boys' lives upside down. Kanat (Eric Tazabekov) is a cousin living in a city, and he brings city toys with him. In his extravagant clothes, with a hoverboard and a tablet, he appears like the alien intruder. Not only he brings those emblems of civilization (and the nature vs modernisation clash trope emerges) but also causes a rift among the brothers, who feel tempted with the world he symbolizes on many levels. Besides overwhelming anxiety, what accompanies Kanat is a constant buzz, be it the digital noise from his tablet, or the terrifying newsreels from TV, plus the economic concepts and erotic tensions.

The four siblings now tend to disobey and put idle play above the obligations, which confronts Aslan with his threatened authority. The power slips from his hands and he doesn't enjoy it. His ways as leader will be tested. Kanat's character is not a simple destroyer. He symbolizes a temptation, and even a trial – the test of brother's relationships and also of Aslan's humanity. Kanat can also be seen as the symbol of civilization or just the outside world that affects the children, no matter what effort their parents take to protect them from dangers and atrocities.

With the thoughtful direction of Baigazin, the story of idyllic haven turns into the loss of innocence tale. In can be read through different interpretation keys, with Biblical parallels quickly coming up to mind. The parabolic nature of the narrative is reflected in an austere form. Every frame is like a work of art, reminding rigorously composed paintings. The director took the role of cinematographer (he also wrote, produced and edited the movie, drawing from the best traditions of auteur cinema), and cited Yasujirō Ozu's usage of just one lens, expressionist paintings of Franz Marc and the structure of stained glass orthodox churches' windows as his inspirations.

Carefully selected, subdued color palette, the smart usage of sound and silence, the contemplating rhythm allowing the story to unfold in wholeness and harmony, complete the narrative perfectly. This hypnotic, parabolic tale, subtly painting the moods and precisely constructing the space, brings to mind various works of masters of contemplation. Baigazin, despite being at the beginning of his artistic road, seems to be α mature and conscious creator, perfecting his distinguished style. He is definitely an auteur to watch out for in the future.