Existential Prison Sweats

Of all Takashi Miike's large body of work, “Big Bang Love, Juvenile A” is perhaps his most metaphorical film. Many of his films can be wild, crazed and surreal, but with “Big Bang Love, Juvenile A” the director walks upon an experimental path, poetic in execution. There is nothing real about this film, but truth of the human condition crawls and scratches to the surface, in this claustrophobic fever dream. Symbols bombard the viewer, metaphors bounce! Incredible lighting and striking visual design that are both theatrical and abstract. There is the occasional cinematic bravura moment, as the protagonists walk through strange corridors and chalk lined prison cells. Sweat permeates the atmosphere, as desire, anxiety and violence intoxicate. This is strange expressive cinema that is visceral and earthy, as well as abstract to the point of the confusion. There is an inherent music that weaves throughout this meditative film, the absurd, cruel and tragic nature of violence! Determinism, whether inherent or through environmental factors, is the philosophical serpent that is chewed upon.

Buy This Title

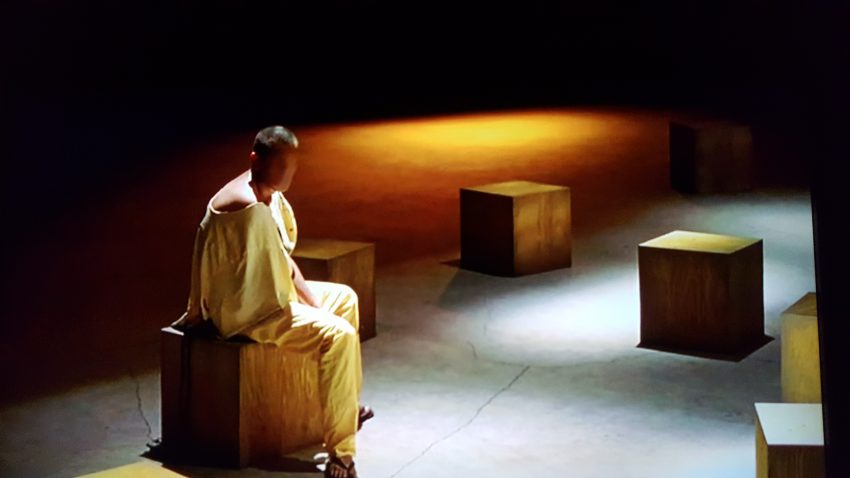

As with any art film, the design is everything and the set design within “Big Bang Love, Juvenile A” is incredible. The whole film is like a chess game of design, lighting and cinematography; all in harmony to create an ironically disrupted world, of strange glows, steamy atmospheres, claustrophobia and acute angles. German Expressionism, Film Noir and the early films of Orson Welles roam through Miike's palate. Derek Jarman's style artifice wafts through the film's oeuvre. The electrically charged homoeroticism, jealousy and confusion, breed tension. This disorientation reflects the unsettling prison world and the maelstrom of the character's inner selves, though external visual metaphors invade the prison constantly. These are the potentials! The possibilities! If only the inmates could overcome their inherent contradictions. An inmate still can strive for the stars and ascend to heaven, whilst rotting in hell!

If you could categorise “Big Bang Love, Juvenile A”, it would be as an existential arthouse prison film. As this is a Takashi Miike film, popular genre motifs raid the film at will. Miike can't contain his wildness, even within this very contained film. There is a crazy jumble of cinematic ideas that are whisked in a cauldron.

This prison drama is set in some uncertain near future, where a murder occurs and police investigate. Detectives and police procedural is blended in the mix! There is a sequence of modern dance! Ghosts appear! Ancient Mayan temples stretch off into the distance! An art nouveau CGI rocket ship blasts off into the stars! Animated moments transpire here and there. There are almighty rumbles in the prison, with wild front kicks and massive punches. There is male desire in the feverish hellhole, with gossip and jealousy rife! “Big Bang Love, Juvenile A” has genre tropes galore, and this a short film at 85 minutes. Ideas are crammed in, but there also long pauses, philosophical asides, desire and death. The two police detectives act as a dispassionate Greek Chorus commenting on the action, as they try to find out ‘who done it?'!

The Professionals

Takashi Miike gathers around him a cast and crew of consummate professionals, creating a spectacle of cinema. The process of adapting the film is given to Masa Nakamura, who has previously written intriguing scripts for Takashi Miike. He has written the road movie “The Bird People In China”, the surreal “Dead or Alive 2 : Birds” and “Young Thugs : Innocent Blood”. Masa Nakamura has written the recent Takashi Miike yakuza film “First Love”. The script is adapted from the novel “Shōnen A erejî” written by Ato Masaki. Ato Masaki is a pseudonym for the writing collaboration between Ikki Kajiwara and Hisao Maki, under one name. Masa Nakamura teases out the existential themes that interest him, and Takashi Miike provides his absurdist twist.

Nao Sasaki is the art designer of this film and it is an incredible piece of work by this craftsman. Sets are constructed immaculately, to give a strange abstract feel; Brecht, German Expressionism, the claustrophobia of Film Noir. The sets have an autocratic feel, which accentuates the absurdism, as well as ramping up the existential anguish the characters, from the warden, down to the inmates. Space is contained and constrained, to elevate the boxed in nature of the prison. The only part of the prison that is lightly lit is the laundry room, which is like a decaying factory. The characters have the opportunity to walk in this space, which gives them an added dimension to express their inner selves, and augments mystery to the film. The external shots, in flashback, are more contemporary; streets, a bar, a bedroom, a bathroom. They are generally more conventional in design, even though acts of appalling violence occur here. Wittily, these are the only ‘naturalistic' scenes in the film, in terms of the sets and lighting. The conventional nature of murder!

Masahito Kaneko's cinematography is both apt and intriguing, with German Expressionism, and Film Noir style camera work at play. Half the screen can be blocked off by a wall, as a character, is constrained, suffocated within the frame. There are the big cinematic shots with alternates of light and dark, as the new inmates walk through this surreal prison. Space is trapped by corridors, but when the shot opens out, there is a thin line of abstract light in which inmates sit within chalk lined cells within the centre of the frame, but darkness envelopes the rest. This is bravura compositional camera work, in rhythm with the lighting and abstract set design.

The lighting throughout the film is immaculate. The sweaty decadence of the laundry and communal bedroom is accentuated by the warm smoky lighting. The dark is pierced with hazy blues and lime green glows, especially in interrogation scenes. The warden's mad smile is stressed through light, to express his personal torment; a man at the edge of his tether.

The cast is excellent, from the younger actors to the older campaigners. This is mainly an all-male affair, in an all-male prison, though the screen is invaded by a female ghost, to disrupt the plot in an unusual manner. Like a Shakespearean ghost, she appears to cause action, but the manner of her intervention is intriguing in this masculine environment. The other main feminine influence is through the actor Ryûhei Matsuda, who plays the scared, perplexed, but effeminate protagonist, Jun Ariyoshi, even though he's just killed someone and mutilated his corpse! This aspect of the story is never really elucidated upon, apart from the fact his character is an outsider now locked up in prison. Ryûhei Matsuda pretty boy good looks have been used to cause chaos in an all-male environment before, in Nagisa Ôshima's “Taboo” from 1999. Takashi Miike uses his unusually beautiful face for a different effect, as Masanobu Andô who plays Shiro Kazuki, is the real cause of the prison gossip; as he is the one who drives desire, violence, jealousy and fear within the prison.

Shiro Kazuki is all uncontrollable Schopenhauerian Will, all drives, energy, violence and Alpha dominance; this is also the root of his tragic character. Ryûhei Matsuda plays Jun as an almost perplexed fish out of water ingénue murderer. Only in a Takashi Miike film can there be a male ingénue killer! Jun is confused by Shiro and he is trying to figure out what the hell is going on in this bizarre prison. Ryûhei Matsuda portrays Jun's slowly developing desire, affection and fascination for Shiro, as well as his bewilderment at Shiro's erratic behaviour and protection. Masanobu Andô is magnificent as Shiro, one minute all impulse and violence, the next filled anguish, fear and despair. Masanobu Andô performance is both subtle and outrageous, filled with energy, then to be struck down with a wasteland injected ennui.

The warden is played in an oft-kilter bizarre fashion, full of German Expressionistic weirdness, by Ryo Ishibashi. He is superb as the severely damaged and despairing Warden, the authority figure frozen in memory. Ryo Ishibashi is an alumni of various Takashi Miike movies, “Audition” being his most famous appearance. One of the cops is played by Kenichi Endō, another regular in Miike films. He investigates a murder in prison with main detective played by Renji Ishibashi. This very experienced Japanese actor who has featured in the “Lone Wolf And The Cub” films, to “Tetsuo The Iron Man”, through to Takashi Miike's “Dead or Alive” and “Ninja Kids”. Both play their roles in a rational disinterested fashion. This is a very strange juxtaposition to the sweltered hell of the prison, all angles and strange glows. They smoke cigarettes, contemplate the murder, oblivious to the deranged environment. This absurdist detective plot addition enhances to the experimental nature of the film. The cops act as rational Greek Chorus, examining the action and motivations within the prison, though not the boiling intuitive agonies of the victim. Takashi Miike examines Shiro Kazuki character poetically, through philosophical dialogue, visual metaphors and dance!

The unobtrusive and subtle music score is composed by Kôji Endô. He is Takashi Miike's regular composer, who has scored many of Miike's films. He started with 1997's “Rainy Dog” to Miike's most recent effort “First Love' in 2019. He keeps things generally minimalistic and electronic, but does switch to conventional instruments in some scenes. He uses piano motifs, an accordion, and simple percussion for one moment. The occasional dissonance invades the score. He uses collages of sounds, such as mobile phone ringtones, computer bleeps, blending in with percussion, with repeating minimalist chord progressions of synths. The music in the intriguing dance scene, Endo goes for full-on experimental electronica, a quiet loud motif, with pulverising rhythm broken up with gentler early style krautrock Kraftwerk like vibes.

The Agony Of The Will

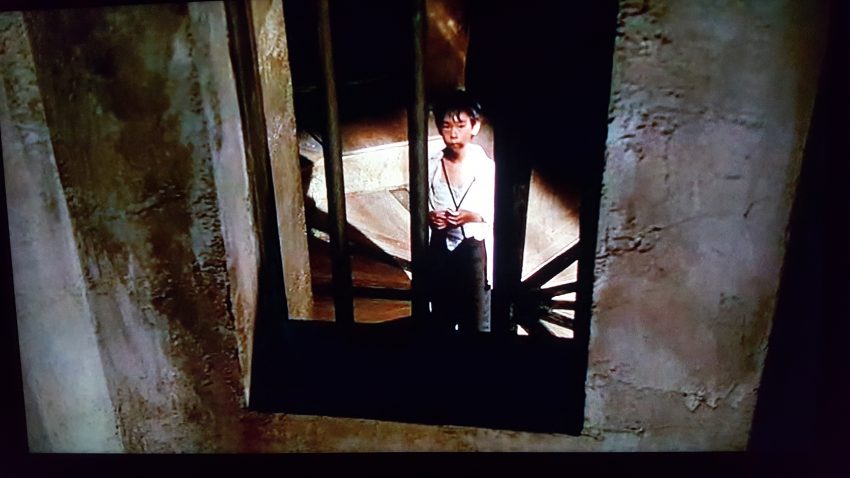

The heart of the film is the rage and torment of Shiro Kazuki played by Masanobu Andô. Shiro is a very violent man. He has already done time for raping a woman, and now he's back inside for murdering a young man. He beats an unnamed young man to death, for no reason that is given or that is apparent. He just killed the poor fellow on a whim. He enters prison with the softer centred Jun Ariyoshi. Jun killed a man in self-defence, after being sexually assaulted. What puzzles the authorities is that he mutilated the corpse of his abuser, in a rage of absolute violence, chopping him to pieces. Jun and Shiro enter the prison together, both in bloodied in white clothes. Shiro advises Jun what needs to be done, in the process of becoming an inmate. This is the beginning of their bond.

The narrative structure of the film is non-linear, but the two protagonists meeting is an important clue to unlocking the nature of the film. The timeline bounces back and forth. Shiro is dead, with Jun straddling his corpse, seemingly throttling him. Cops enter the prison to investigate the murderer and nothing is straight forward. Through disinterested investigation they solve the riddle, but they don't understand it, but the law is served. Scenes are replayed, either as the ‘straight' narrative, or from the cops point of view, in flashback, or Jun's point of view, or Shiro's memory, it is riot of perspectives. The investigating cops are usually are accompanied with Godardian titles.

The beginning of the film features one of the cops contemplating the nature of light years, in time and space, in relation to the earth. This is one of the subtexts the film explores, scrutinizing reason and rationality, where there seems to be none. The film is punctuated with Shiro fighting inmates or guards, all flailing punches and powerful front kicks. He instantly affirms his alpha status, after the inmates start to bully the effeminate Jun. His violent behaviour takes both the inmates and Jun by surprise, as Shiro batters everyone in submission. Shiro is the top dog. Jun is puzzled by Shiro and contemplates Shiro's strange behaviour, as well as developing a physical desire for him. Jun treads carefully, as Shiro's nature is dangerous, erratic and perplexing.

Shiro is the very centre of the prison gossip within the washroom. The inmates discuss who he has beaten, rumours of who is having sex with. The other main inmate, who wields power within the prison, is Makoto Tsuchiya played by Kiyohiko Shibukawa. He works in the infirmary and can obtain narcotics. He deals drugs for sexual favours, but sexual jealousy drives this character. He murdered his wife after he discovered she was having an affair. Many of the inmates claim they are not homosexual, but will do sexual favours for narcotics, which Jun is confounded about. Jun admits to being indifferent to woman, but he says he's not too keen on men either. Makoto has a special favourite inmate he likes to have sex with. Jun covers for him within the washer room, when Makoto demands his presence.

As Jun and Shiro's characters interact, Jun's desire transforms from the more overtly erotic, towards something deeper. As Jun worked in a gay bar as a civilian, everybody assumes he is homosexual. If he is the only homosexual is prison, then he's not having sex! Everyone else seems to be, even though they are supposed to be straight! The rules of mainstream Japanese society have seemingly been turned upside down in this all-male hothouse. Miike's wit almost winks at us from the screen.

There are visual symbols outside the prison that are used as metaphors. The cramped claustrophobic prison is suddenly expanded into massive vistas, where inmates can stretch their legs outside. Absurdism is used to explore the idea of space. Jun and Shiro, in these moments of absurdist calm, enter a Buber-esque encounter, as they converse and express their inner most desires and learn from one another. Ironically, these are the moments Shiro becomes aware at the horror of his own being; the nature of his Will and his inability to control himself. Shiro comes to understand that he is capable of rationalism, but the nature of his experience and environment has turned him into something very different. He is a creature of irrational impulse, and a deterministic self-destructive Will that is all drive, but with no particular end in sight. He is all means to a Nothing. This horrific revelation pushes him to take absurdist action.

The eccentric external vistas of a massive ancient Mayan temple and an art-nouveau style CGI rocket ship, from the era of “Flash Gordon”, physically express Jun and Shiro's inner world. The rocket portrays the world of reason, science and rationality, that wishes to take off and explore the stars. This is the dream of escape for Shiro. The Mayan temple points toward are more intuitive, contemplative realm of the heart and spirituality, the possibility of heaven, which Jun is attracted to. The idea of a heaven sends shivers down Shiro's spine, due the nature of his ‘heavenly' experience into manhood. These poetic and philosophical scenes are interspersed throughout the narrative, again breaking up formal expectation of what a film narrative should be. The way the scenes weave one into another, throughout the film, enhances the seeming chaos of the narrative, but it does have a purpose. Why is Shiro dead? How is Shiro dead? Who Killed Shiro? The answer is both absurd and tragic.

The early scene of the abstract dance sequence is the key to Shiro's trauma and his development into a male of pure irrational Will. The dance is high energy and twisted postures. When the young boy is called towards this mysterious young adult male, an elderly man tells him he will taste the initiation of manhood by the throat, and it will give him power! A massive abstract moon is in the background. After this horror, the young boy is in some kind of enclosed room, eating a chocolate bun, looking out of a small window, where a triple rainbow shines. The irony is that Shiro wishes to overcome this horror, and he can only find one solution that will work out for everybody.

The disturbed warden enhances an uncanny subplot to this tale of derangement. He is a widower with a cracked smile. He is a broken man. His wife committed suicide, after she was raped. The abusive criminal who committed this terrible act is Shiro, and through a bureaucratic error, Shiro faces the wrath of his victim's husband. The trauma of his grief seems to have overwhelmed the warden, with his shattered smile. Strangely, he doesn't act upon an impulse towards revenge. When the cops investigate, they unravel this drama within a drama, and The Warden is a suspect, but they quickly dismiss him. Shiro is anxious around the Warden, though his own guilt seems to be at the root of this tension. A Shakespearean plot device is added to the maelstrom of images, as the Wardens' wife appears in one scene. She is a ghost straight out of J-Horror, a grey shadow, squatting, all legs and hair! To Shiro's horror, this disturbing shade forgives Shiro, which isn't the answer Shiro expected or was looking for. There is no Fury going to relieve Shiro of life!

Shiro incubates an idea after a traumatic moment with Jun, as they talk outside, by the Mayan temple. It is raining and a triple rainbow appears. This is the moment Shiro falls apart. Under his interrogation, Jun tells the policemen that the rainbows finally caught up with Shiro. Shiro is paralysed by the symbolism of the rainbows and his traumatic past. Jun tries to comfort and hug Shiro, which Shiro rejects. Love is not the pathway out of the situation for this broken and violent young man. He is man of almost mythical uncontrollable drives, and he finally rationalises this.

The police solve the crime after the drug dealing Makoto attempts suicide, but he is stopped from killing himself. He has left a long letter detailing events, which had led to Shiro's death. The cops are still puzzled that Jun was found throttling the corpse of Shiro. Makoto is the inmate who attempted to murder Shiro. Makato's favourite inmate for sexual favours tells him he is having sex with Shiro, even though this is a cruel lie. Rumours about Shiro's affairs, or even rapes, have been common among the inmates for a while. These rumours set off Makoto's paranoia and jealousy.

The police can't find any evidence that Shiro has been raping or having sex with anyone within the prison. Shiro doesn't put a stop to the rumours either, which he could easily do through his ability for violence and fear.

In a moment of jealous rage, Makoto attempts to strangle Shiro with a piece of cloth, as he sleeps. This is the moment Shiro has been waiting for, but with his inherent will power and alpha male drive, he realises Makoto is not up to the task of his murder. Shiro can sweep him away like a bug. He overcomes, or ironically meets his moment of becoming, by grasping Makoto's hands and then throttles himself with the use Makoto's hands. Makoto is powerless to stop him, a marionette used as the instrument of for Shiro's demise.

Shiro is just too tough to kill in this prison, so he kills himself, through an unwilling participant, who he completely humiliates. Makoto is a dangerous, violent criminal, but he is just not dangerous enough, and Shiro's Will completely overcomes and dominates Makoto's being. This leads to Makoto's own existential crisis, which the prison guards and inmates intervene upon. Makoto is now a criminal with no face, Shiro's last act of cruel destruction.

This is pretty crazy stuff, but falls into the existential literary tradition of Camus' Meursault or the deranged revolutionary Alexei Nilych Kirillov in Dostoevsky's “The Devils”. Shiro overcomes his Schopenhauerian Will-To-Life drive and instinct with an ironic use of Nietzsche's Will-To-Power; he murders himself with an act of self-overcoming by overpowering his own violence driven Will-To-Life. Shiro's trauma is too deep and all-encompassing. He is man of violence and he has no control over his drives or his life. The only control he has in his life is to end it. This is a truly tragic situation and Shiro is a tragic character. Violence begat violence, he decides to break the cycle of violence, and abuse, in the most extreme way possible!

Jun is heartbroken at his death and he strangles Shiro's corpse due to his anger. Jun rages that a stranger tried to murder him. Shiro should have asked Jun to end his life. Jun comprehends Shiro's erratic violent behaviour, within the prison, is due to his search for death. Shiro is just too wild and strong for it to happen within the prison system. Shiro sits at the top of the pile, and death isn't forthcoming. Jun is saddened by Shiro's foolish and bizarre method of euthanasia; Jun would have simply killed him out of affection. This is a witty and deranged moment of Takashi Miike style Romanticism! Jun wonders, if it is finished?! Is there anything after death or is there nothing? Shiro cannot answer… “Big Bang Love, Juvenile A” is a strange and sad film, crammed with memorable visual images. Takashi Miike examines abuse, domination, violence and determinism, in an experimental style. All that is left is destruction and broken lives.