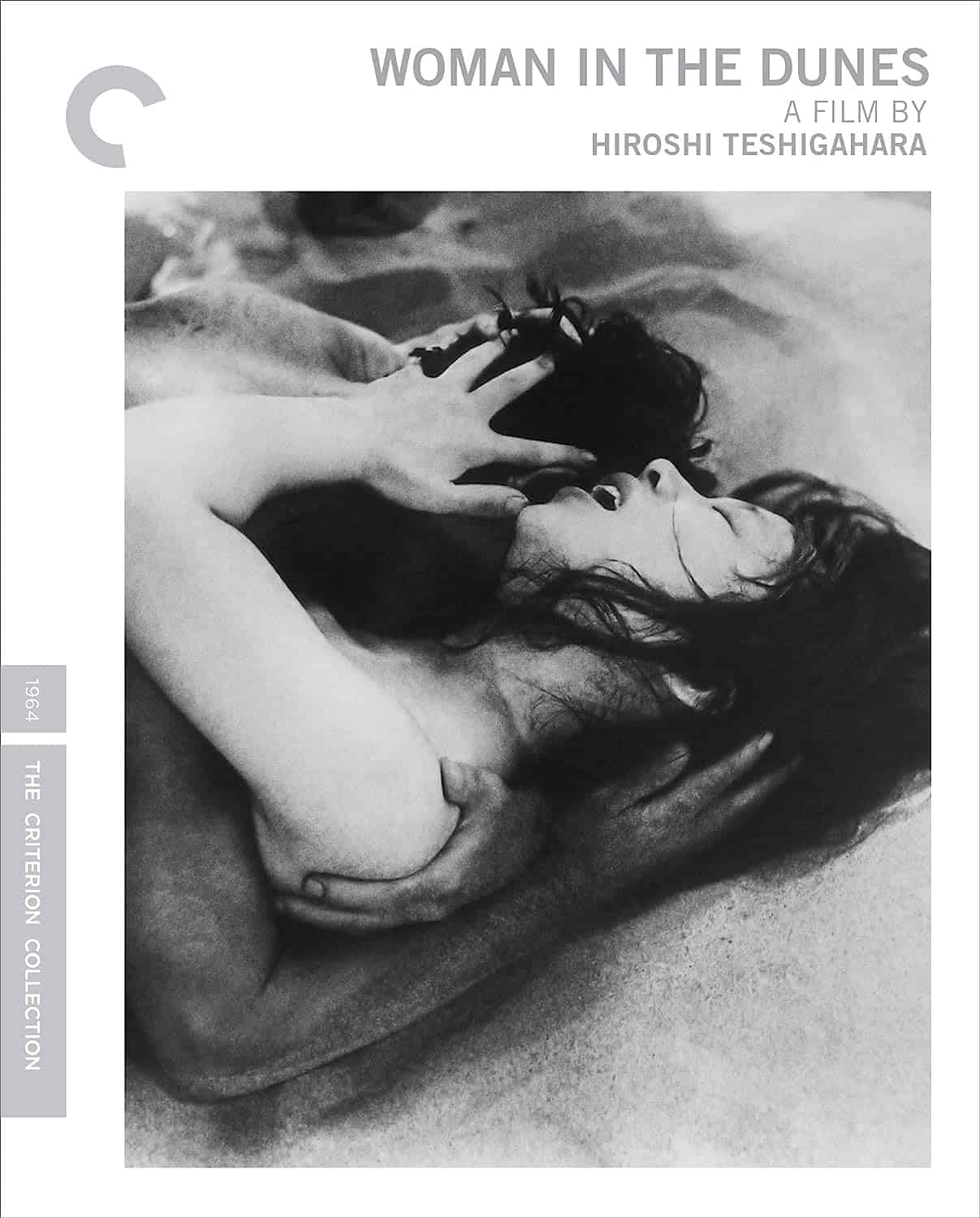

As much as I would like to stay optimistic about this film by the Japanese avant-garde film director Hiroshi Teshigahara, it is essentially an exploration of the meaninglessness of life and draws a sort of parallel with the myth of Sisyphus in its overarching theme of existential crisis throughout the film. The predicament in which we find the schoolteacher and part-time entomologist trapped in, when he is given a place of shelter to spend the night after missing the last bus back to town, chillingly resembles our own helpless obligation to continue in our daily monotonous routines without any greater reason than to simply survive. The rhetorical question raised by him later on, seems to be directed at us as to whether we struggle to survive or survive to struggle.

However, the significance of this film, lies not just in the visual depiction of the harsh reality of post-war ‘kyodatsu condition' that the artist community in Japan had to face but also in the manner in which it plays with the formal elements of the film itself, subverting conventional modes of film making and cinematography. What is important to notice is the resonating essence of symbolism throughout the movie. The sand seems to have a will of its own, with its water-like quality, it seeps in through cracks and crevices, a living and breathing creature of the night, it creeps in and tries to swallow and at once bury the inhabitants struggling to survive at its core alive. There is no escaping it because the sand will never wait. just like time never stops for anyone.

Check also this article

Like in typical magic realist settings, the protagonist seeks to escape from civilisation and welcomes solitude in a bizarre land where the sand is everywhere; from the food they eat to the bare skin of their body. It covers them in a fine layer of dust submerging them in a spirit of oblivion, existing totally cut off from the outer world as they live surrounded by the devouring sand on all sides constantly under the impending threat of being buried alive in their pit while they sleep.

Teshigahara deliberately chooses to focus on a small grain of sand at the very beginning and then zoom out to include the complete expanse of the desert stretching far and wide. The teacher's role as a new husband of the widow living in that abandoned state reflects our own insignificance pitched in contrast to the larger context of the whole world as anonymous individuals wandering in the open, like the tiny granular particles of sand lost amid a vast ocean of sand. Segawa's clear and detailed cinematography in this film has given the sand a life of its own.

The woman recounts how her husband and daughter died in a sandstorm and their bones were probably buried underneath these sand heaps. Even though it seems illogical to the viewer and even to the teacher, her explanation provides her with enough purpose in her life to keep struggling to survive in this never-ending situation. Despite its lack of logical grounding, the film is peculiarly also very realistic, especially in the way the camera regards the naked skin of the woman while she lies asleep with her back to the teacher and gives us an almost tangible sensation that has nuances of eroticism in it. Her acceptance of her fate, though shocking, is still considered somewhat understandable, given her reasons to stay next to what is left of her family. However, it is the gradual transformation of the otherwise rational man into losing his motivation to escape, such that he ends up choosing to stay in that sand pit, that leaves us absolutely horrified.

In a strange way, re-watching this film again after years reminded me of a line from the famous song, ‘Hotel California', which goes like, “you can check out any time you like, but you can never leave”. When the unsuspecting schoolteacher is led to the young widow's house to spend the night, he willing walks into his own grave without even realizing that. It is only the woman's words “not on the first day” when he offers his help to shovel the sand, that makes us wary of the whole negotiation with the villagers. The next morning when he gets ready to leave and finds the ladder missing, he finds it amusing. But the jarring notes of the background score by Takemitsu mocks us of his confidence in the people who helped him. Whether they helped him or trapped him, is left to the viewers to interpret and so is the decision to read this film in a cynical or optimistic light.