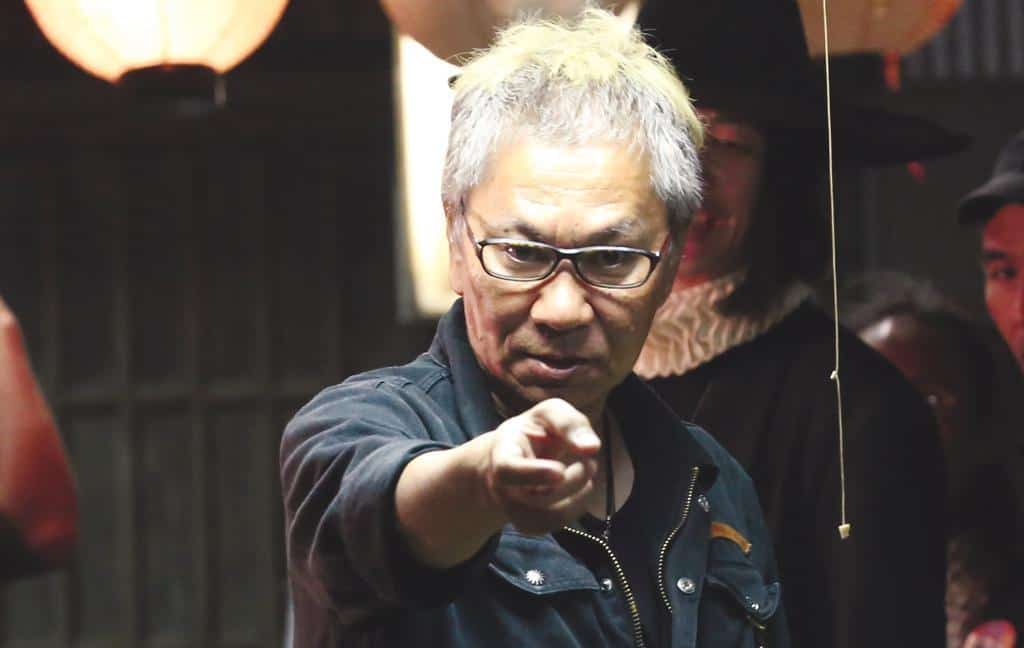

YING Liang (1977, China) graduated from the Department of Directing at the Chongqing Film Academy and Beijing Normal University. He made several successful short films before directing his first feature, “Taking Father Home” (2005). In 2006, he made “The Other Half”, which was supported by the Hubert Bals Fund of IFFR. In 2010, his short film “Condolences” won a Tiger Award for Short Films in Rotterdam. “When Night Falls” (2012) won prizes for best directing and best leading actress in Locarno.

On the occasion of “I Have Nothing to Say“, screening at International Film Festival Rotterdam, we speak with him about the film and his personal connection with it, teaching, the sociopolitical situation of China and Hong, and many other topics.

To what extent do you feel your time spent teaching filmmaking has had an influence on your own filmmaking?

The good thing about teaching is that it makes me become more conscious, while learning a lot about film production, history and concepts. The bad thing is, however, knowing too much may make me lose the courage and the obscure consciousness of creativity. It is possible that there may be a balance between the two, but it can't be totally anticipated, and this is also something very wonderful about teaching filmmaking.

I can't make films everyday, but I can teach it everyday. So, all in all, I very much enjoy teaching film.

Much of “I Have Nothing to Say” seems autobiographical. To what extent is that true and are any particular personal experiences that feature the film?

Yes, you are right, this film is my autobiography, or, to be more precise, my semi-autobiography. I had a similar trip in real life, but it was my mother-in-law and a few relatives of mine, whom we (my wife, my son and I) met in Taiwan instead. I haven't seen my parents for 5 years. To me, the short film has given me a chance – as I was writing the script, I was able to imagine my mother's life in the past 5 years from her point of view, as if I went on a trip with her. Some of the lines in the short film come directly from the actual conversation of my mother and the police, whilst some are further developed from the record of that conversation.

In fact, when we shot “I Have Nothing to Say”, we shot a feature film named “A Family Tour“, at the same time. The short film and the feature film tell the same story. The difference is that the short film tells the story entirely from the mother's own point of view, whilst the narrative voice in the feature film is from all the 4 members in the family, especially the 3 adults. The 3 adults have more or less equal proportion of narration. We plan to finish all the post-production work of that feature film the coming early February.

Why did you decide to shoot the film in black and white?

The short film is in black and white because it is solely from the mother's perspective, whilst the feature film is in colour and more realistic in general. More conflicts between the characters, and the inner conflicts within each of them, are shown in multiple layers.

Can you tell us a bit more about the film's ending, particularly the fact that the mother does not hug her daughter? Do you feel this is a sad conclusion for her, or does the mother feel too much distance from her daughter at that moment?

The mother's illness is one of the important reasons for this trip: all that the mother wants is to see her daughter's family so that she can leave this world in peace. The situation in China is another important reason for this trip: if Yang Shu continues to make films, she will not be anywhere close to mainland China. So the family has to see each other, even just for one single last time, before the mother dies. Yang Shu's insistence on being “politically correct” has constituted the main conflict between her and her mother, and her mother has no choice but to succumb to the authorities, as she lives in China. The tour group is like a mobile China, like a prison. The Chinese tour guide is the representative and executive of that prison. The dilemma of the family in the film is that they have done everything they can to make their reunion possible, but still they can't escape from the destined final separation. It would be very difficult for them not to see each other, but it is even more difficult when they really do. And this is an absurd situation, isn't it?

As the end of film is also the end of the mother's life, the ending music is in fact the Buddhist farewell music which releases souls from purgatory.

Can you tell us a bit about the casting process?

I started casting in October 2016, and conducted six workshop series with the actors between March and June in 2017. Each series lasted for 3 to 5 days. Back then, we were yet to have enough funding to finish making the film, but I considered writing and working with the cast very much the core of the creative process, and it was also my responsibility as the director. As it was scheduled to start the shooting in June, no delay of the two tasks could be justified. So I simply had to put aside my worries for the budget.

Nai An and Gong Zhe, who play the mother and the daughter respectively, are from Beijing. Pete, who plays the husband, and the little boy who plays the son are from Malaysia. I live in Hong Kong. The film was shot with a local production team in Taiwan. I can't enter China and the cost of filming in Hong Kong and Taiwan is very high. So I conducted the workshops with the actors in Malaysia instead. We prepared the actors by watching films, reading various materials, rehearsing, discussing and simply getting along.

Since what I want to say in the film is what I consider the fatalism of the Chinese people: every generation experiences the same problems; and since the work of the protagonists Yang Shu and her husband are related to underground and semi-underground independent Chinese films, the actors' understanding of modern and contemporary Chinese history and of independent films becomes very important. Our rehearsals weren't simply about acting out the scenes from the script, but included a series of discussions about some hypothetical, off-script scenarios among the cast and I, such as “how would the characters act and behave in other situations?”, “what would the characters do in a certain situation 5 years before or 10 years after the story of the script?” and “where would they be and what would they do during the Sichuan Earthquake?” After our discussions, they would then act out those scenarios. Then we would discuss again, and make some adjustments in another round of acting. I would also make adjustments in the script as we rehearsed. They were very fine actors, and we accumulated a lot of thoughts and experiences during the 4-month preparation. All that materials and experiences were effectively utilized in the actual shooting. Such preparation has nurtured the inner connections among the actors as family members in the story, and this was the least I would like to achieve.

How about the location the film was shot? And were there any memorable episodes during the shootings, good or bad?

The main shooting location is Kaohsiung, in Southern Taiwan. Unlike Taipei, Kaohsiung isn't a political center, so the atmosphere there suits the film very well. Our shooting was done very smoothly, one reason was that we had an excellent production team, some outstanding actors, and thorough preparations. Another reason was that the culture department in Kaohsiung has been very supportive towards film productions.

Much like the recent “Ten Years”, there have been a lot of concerns over the increasing Chinese influence on SAR. How do you feel about these anxieties as a Shanghai native working out of Hong Kong? And how do you feel your work may differ from Hong Kong natives looking at similar concerns?

I came from a totalitarian country, and now I'm living in Hong Kong, a place that is also becoming more and more totalitarian. I totally understand the anxiety of Hong Kong people, in fact I am even more worried than they are, this is because I know what totalitarianism is like. We can never regain something once we lose it. But I am more hopeful and optimistic than them as I still see a certain level of freedom in Hong Kong, although we're losing some of it day by day, but there is still the possibility of standing up for freedom.

What, if any, changes do you believe will happen in both Hong Kong and Chinese cinema over the next decade? Do you see an increase in films of a more political nature looking at relations between Hong Kong and China?

There are more and more independent films with views that are different from that of the Chinese mainstream films. These films can't be shown in mainland China, that's for sure, and because of the pressure from China, it is also getting more difficult to show these films in Hong Kong. 10 years later, perhaps, the situation of Hong Kong independent films might be just like the current situation of Chinese independent films – the government shuts down all independent film festivals, as if writers and directors are the enemy of the country.

Which are your favorite filmmakers/films?

I have a lot of favourites to be honest, and the list is constantly changing. My most favorite director is Emir Kusturica and his film “Underground” is my favourite film. I recently watched “120 Beats Per Minute”, and I really liked it too.

Can you tell us a bit about your future projects?

For the time being, It's just that feature film, “A Family Tour”. It will first be shown at some film festivals, then released in cinemas, no chance to be shown in mainland China though.