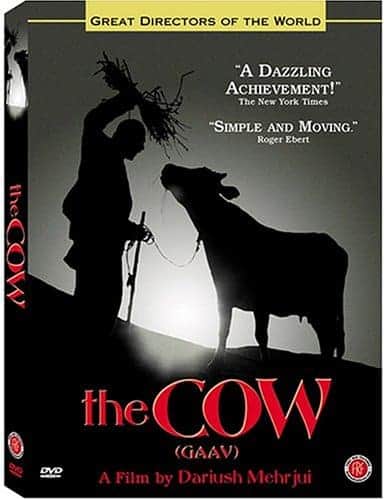

Often considered as the first film that began the Iranian New Wave, it is also historically well-known for gaining admiration of Ayatollah Khomeini which saved the Iranian Cinema from being banned outright after the 1979 Revolution. Many of the later film directors such as Kiarostami, Panahi and Makhmalbaf were perhaps greatly influenced by Mehrjui's works.

Buy This Title

In this film, The Cow, Mehrjui narrates the tragic tale of how a man who deeply loves his cow laments her death and his consequent descent into madness as he finds it difficult to cope with his loss and grief. The film not only does justice to the character it attempts to sensitively portray, with special emphasis on the human psyche at action here, but also closely studies the poverty and sociopolitical conditions of rural Iran.

While the faces and gait of the rest of the villagers seem to be marked by their exhaustion and the strain of constant unrewarding labour, it is only Hassan and his cow that seems to be vividly alive, frolicking in the water and reflecting their intimate relationship that transcends the ordinary owner and cattle bonding. Their relation borders on the role of a parent and child or even mirrors the union between a lover and his muse (as suggested by Sufi beliefs) which gives it a particularly Iranian perspective. Hassan associates his cow with his distinct identity and social status in the eyes of the other villagers. His affection for his cow is much more intense than that for his wife whom he refers to as only a woman, frequently sleeping in the barn to accompany his cow; such is the depth of his feelings for the animal.

It is important to realize that this film is open to multiple interpretations and can be analyzed from diverse angles, be it from the psychological and emotional turbulence that Hassan undergoes after losing his only means to livelihood, the recipient of his unconditional love or the object of his social pride and source of his identity; or the parallel allegory that it presents with the socio-political conditions of the country in that post-war era. However, also it helps to show us how nuanced the intrigues and implicit deception that most rural communities harbour among each other can be in response to their being extremely close-knit yet solely preoccupied with the purpose of mere survival, even if that meant to resorting to cruel and inhumane methods and participating in immoral actions such as lying or torturing a mentally disabled person.

What is most disturbing to watch is not Hassan's gradual and perverse transformation into his cow, as he claims that “I'm not Hassan, I'm Hassan's cow” but the fact that the villagers accept this change nonchalantly and subsequently treat him as a “beast”. like the one he believes himself to be. This shows how afraid the rural inhabitants of Iran must have been and how bitter with their miserable living conditions to accept and tolerate anything that life gave them, no matter how peculiar and illogical it may appear to be. They choose to blame all the root causes of their problems to their neighbouring community, referred to as the ‘Bolouris' in the film and depicted as looming in the background marked by three mysterious figures keeping watch over the village from a distance. They are suspicious of everyone who is an outsider and consider them a threat to their security and limited resources.

Ezzatolah Entezami who plays the protagonist is mesmerizing in his acting, as he undergoes the Kafkaesque metamorphosis and imagines himself to be the cow. In his desperate search for his own identity which becomes shaken up after he discovers the disappearance of his beloved cow, he sits quietly on the roof looking out at the pastures, waiting for the return of his cow, not believing them when the villagers told him that she had strayed away. They stand and watch him from a distance, a position we can relate with, being onlookers ourselves. As the day comes to an end and the sky darkens, he slowly loses touch with reality as he realizes she will never come back. Next morning, when he is discovered by the villagers, they find him grunting and raving about, making animalistic noises like the cow and chewing hay. The scene is shot in an extremely close frame giving us a sense of the claustrophobic predicament in which Hassan finds himself, as both the grieving man and the helpless cow being taken captive by his tormentors.

Though the film remains largely undiscovered at international levels, it was one of the first of its kind to create a platform for Iranian movie as being the medium through which artists could raise their voices of dissent and question the politics of the ruling government. By staying authentic in its depiction of the rural experiences and featuring the ordinary villager as its main subject of examination, it effectively reached out and resonated with many Iranian people who were going through similar situations of deception and censorship at the hands of the authoritarian regimes. This approach becomes quite evident in the film in terms of implicit symbolism in the scene where the insane man is dragged by his fellow villagers like a wild beast and eventually beaten to death when he refuses to budge, thus exercising their control over Hassan as a motif of the state authority's dominance over the individual, and is thus still looked up as one of the greatest films in the history of Iranian cinemas.