By Omar Rasya Joenoes

“Are you married?”

“I hate men.”

“Then, you have no hope.”

“My hope is to die.”

The conversation in the search description takes place on a ride home, under the pouring rain. It is initiated by a man, who happens to be Japan's no. 3 hitman, and answered by a woman, who is a suicidal femme fatale. Witnessing their first exchange is a dead bird, hung between them. And in this weirdest of all film-noir films, the scene belongs to a long line of surreal, mind-boggling, out-of-this-world scene after scene after scene after scene.

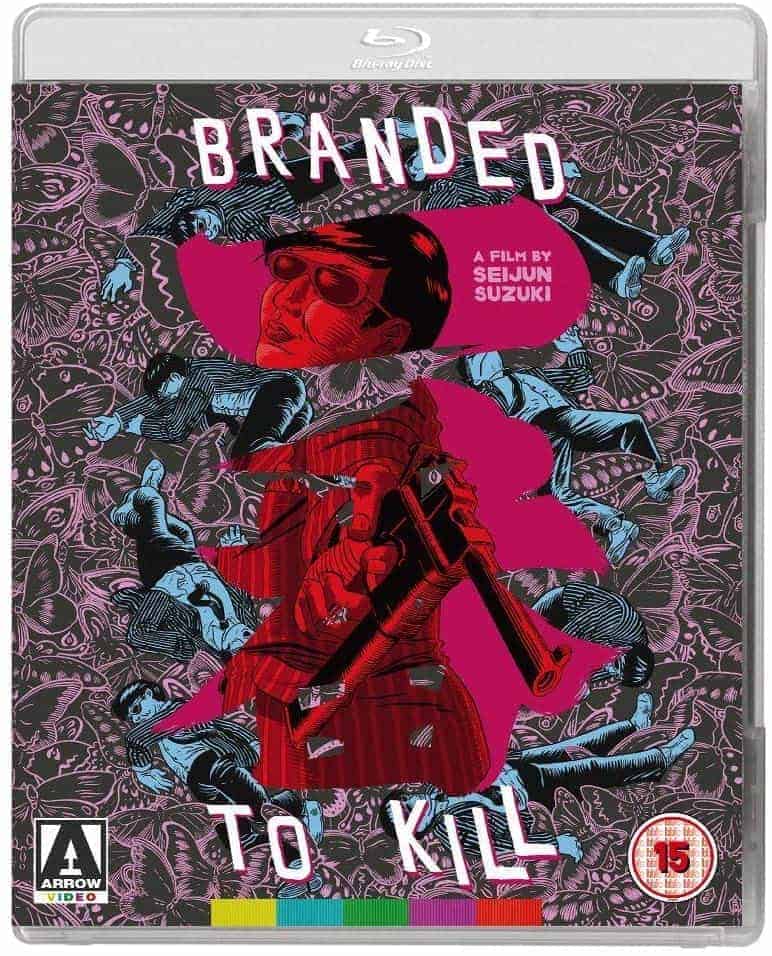

Buy This Title

“Japanese films are weird” is surely a stereotype most of you, if not all of you, have heard at least once before. It is not entirely true and not entirely mistaken. With cult titles like Funky Forest (2005), Hausu (1977), Big Man Japan (2007), Versus (2000), Tokyo Gore Police (2008), RoboGeisha (2009), Tetsuo the Iron Man (1989), Mutant Girls Squad (2010), Vampire Girl vs Frankenstein Girl (2009) and so many others, it's easy to understand why this stereotype is around. Obviously, not all Japanese films are weird, but I am willing to admit “Weird Japanese Films” might in itself be a genre. Years ago, I heard a friend of mine said “Hey, look! That must be one of those quirky Japanese films! Let's buy it and watch it tonight!” to his conservative girlfriend when we were hanging out in a mall. The film in question was Flower and Snake (2004). Those of you who have seen it know why his words are tragically mistaken, those of you who haven't watched it should seek it. To the best of my recollection, they broke up not long after. He told me later he thought the film was an adventure film based on the title. I did not know how their fateful movie night went down, but I am sure I would have found it amusing. The commonly held belief that Japanese films are weird, quirky, unusual and bizarre is innocent enough, I suppose. But when it gives you trouble the way it did my friend, it stops being innocent altogether. Goes to show you that stereotypes are best approached with caution. And this “warning” also applies to “Branded to Kil”l: it's more than just a film, it's an experience.

“Branded to Kill” is a piece of art that truly embraces that stereotype long before that stereotype even existed. The synopsis goes like this: Goro Hanada (Joe Shishido) is a Japanese hitman, known in the underworld as the third best at what he does. He enjoys (and is maybe addicted to) the smell of boiling rice, more so than the sight of his (backstabbing) wife frolicking around in the altogether. Following an action-packed job assignment, he chances upon a mysterious woman, Misako (Annu Mari), who is crazy about death the way he is crazy about the smell of boiling rice. She offers Hanada a task, which he accepts. But he fumbles at last minute because a butterfly decides to rest its wings at his rifle (yes, you read it correctly). This failure leads Hanada to become a wanted man by the underworld, and the biggest threat to his life is no other than No. 1, Japan's top hitman.

If you read the synopsis, it looks like a simple story, with a few weird bits thrown in. But the director of Branded to Kill, Seijun Suzuki, who passed away earlier this year at 94, is never an auteur known to be simple. A maverick among mavericks, he is most known for his work with Nikkatsu. Like many other great Japanese film directors of old, he starts his career working under other directors before he could sit on the director's chair. From the get-go, Nikkatsu saw him as one of their “B-movie directors”, where he is demanded to work fast and cheap. It's normal for him to churn out 2-3 movies per year. He never likes this, and for the bosses of Nikkatsu, the feeling is mutual.

Suzuki's most famous films belong to the Crime/Neo-Noir/Nikkatsu Noir genre. Yakuza films, to be more precise. His first breakthrough is 1963's “Youth of the Beast”. Gate of Flesh, a proto-pinku film which is set in Post World War II Japan, follows in 1964. Then “Tokyo Drifter” appears in 1966, a jaw-dropping combination of action, colors, sets and music. Think of it this way: had Dario Argento directed a Yakuza film in the mood of Suspiria, it would have resulted in “Tokyo Drifter”. For Suzuki, the story was never as important as how it is presented. Even with limited budgets and less than a month in the shooting schedule, his films are always artistic and highly stylized. They never look cheap, are always entertaining and are always moderately successful at the box office. His fan base never includes his own bosses back at Nikkatsu, though. They don't appreciate Suzuki's flamboyance and keep giving him death stares for making his films more and more surreal. “Tokyo Drifter” is too fantastic for their patience and they “punish” him by assigning him to black-and-white pictures.

“Branded to Kill” (1967) is his 40th film and no review is complete without talking about what happened behind the screen. The film started as another production entirely which heads one way to Palookaville, that's when Nikkatsu brings in Suzuki to work on this film. Suzuki immediately rewrites the script and creates the strangest film in his career. It is the last straw for Nikkatsu's top brass and they fire him. Suzuki sues for breach of contract, which is settled out off court. He also ends up not directing another feature for the next 10 years.

Think about it: this is a film so weird it takes its filmmaker out of the business for a decade.

Just how weird it is anyway? That is something I don't think I can put into words, but if you choose to view this picture, be prepared to see:

– A hitman shooting a man up a water pipe

– A hitman getting high on the smell of boiling rice

– Lovemaking in the stairs + what appears to be hide-and-seek + lovemaking outside the window + more getting high on boiling rice + more lovemaking

– A dead body rolling on a rolling chair

– A hitman making his escape by jumping on top of a promotional air balloon

– A seemingly jealous wife materializes behind the windows when her husband is discussing a contract with a beautiful client

– The previously mentioned butterfly on a rifle

– Indoor rain and a roomful of dead butterflies, all pinned to the walls

– A hitman “makes love” to the recording of his lover slowly being torched by fire

– A hitman being tortured by sleep deprivation

– A hitman chiding another hitman for his lack of, erm, bodily control when nature calls. “You need more training!”, he said.

And these are just what I can remember. The film is even weirder. If I were a middle-aged Japanese film executive in the 1960s, I probably would have been befuddled and even offended by the film too.

But this film isn't just weird for the sake of being weird. Many factors contribute to its greatness: the shoot-outs are great to watch, the unusual score, the luscious monochrome cinematography, the precise editing, the superb camera work and the appropriate performances (his tight budget and short shooting schedule mean Suzuki is used to letting his performers interpret their characters by themselves and would only give out directions if he feels they don't know what they're doing). To me, Suzuki's film is one far ahead of its time. No one can make sense of the details of the film, especially if one only views its scenes separately. But viewed as a complete film, it gives the sensation of a familiar story told in a playful manner. This reminds me of David Lynch, in a way, although Suzuki's film is more absurd than any of Lynch's.

Many critics have also mentioned how the film satirizes noir genre conventions, such as in a femme fatale character (usually the bringer of death) who is obsessed with death and the formalized ranking system of Japanese hitmen. And speaking from a personal viewpoint, I found the satire to be funny, in a deadpan comedy sort of way, especially the scenes involving No. 1 (with his 100% professional approach to EVERYTHING) and Misako (whose perpetual smile seems to indicate she found EVERYTHING to be morbidly amusing).

Much like many great films, it flops hard when it is first introduced. Allegedly, both the Japanese audience and Japanese critics found it too puzzling. Nikkatsu's studio head is said to have told Suzuki to quit filmmaking and open a noodle shop instead. It isn't until the 1970s where revival cinemas around Tokyo air the film where it gets its belated local recognition. Its international one arrives in 1980s from film festivals all around the world. Today, no less than Wong Kar-wai, John Woo, Jim Jarmusch, Takeshi Kitano, Quentin Tarantino and Chan-wook Park name Suzuki as an influence.

I hope, the next time someone says “Japanese Films are weird” in my presence, I will get a chance to experience this exchange:

“Japanese films are weird.”

“None weirder than Branded to Kill.”

“What's that? How so?”

“Name me any other film where a man makes out to the image of his lover being licked by fire.”

“….”

I see it as a film-noir like no other, the strangest crime film in existence, the “Japanese Weird Film” to end all “Japanese Weird Films”.