The award winning, Taiwan based artist Chen Chieh-jen (1960) uses his film “Realm of Reverberations” to explore the effects of marginalization and discrimination on a diverse group of people bound by the same environment, Taipei's Losheng Sanatorium. In this documentary, he doesn't only shed a light on the history of the place and events that took place there, but he also tries to give the people, their experiences and memories a voice.

Realm of Reverbations is screening at Taiwan Film Festival UK

Built on a site that by locals was thought to be cursed, Losheng Sanatorium opened in 1930 and served as an isolation hospital for leprosy patients, also called Hansen's disease. It was specifically designed for the treatment of this illness and patients were often admitted by force. The compulsory quarantine the leprosy patients were put in effectively meant a lifelong imprisonment for thousands of them. When a new leprosy treatment was discovered in 1954, patients were allowed to leave the sanatorium. However, thanks to the years of forced isolation, many found it hard to live in the outside world again. Combined with the discrimination they faced due to the illness and their disfigurement, this gave had little choice but to stay and make their home at Losheng.

The facility remained a specialized treatment centre until the end of the 20th century. In 1994 however, the Department of Taipei Rapid Transit System (DORTS) decided to use part of the sanatorium's grounds for the construction of a depot. Patients that originally were forced to live here, now had to fight for the right to stay. They found support from students and activists that formed the Losheng Preservation Movement but to no avail, as the grounds were forcibly cleared in 2008 and the residents were relocated. Demolition started almost immediately and at the moment less than 30% of the original buildings remains.

Chen Chieh-jen tells the story of the Losheng Sanatorium and its preservation movement from four different perspectives. The first part “Tree Planters” introduces the history of the sanatorium and gives a face to some of its residents. The name refers to trees the residents were forced to plant. In “Keeping Company”, we meet a young woman who came to Losheng in 2007. She keeps some of the former residents company and runs a private project called the Losheng Sanatorium Museum. The goal of her project is to preserve records and other items found in the ruins that testify to the illness and discrimination endured by the residents. Many of the former nurses working in the hospital came from Mainland China, in “The Suspended Room” they sing a song from their homeland, but also give testimony on the hardships of their work as a hospice nurse. The final part “Tracing Forward” starts with the testimony of a ghost of a political prisoner. It takes us on a journey through Taiwanese history, from the Japanese colonial period to the present. Losheng Sanatorium is a part of this history and the ghost seems to question the similar treatment of prisoners and patients and the repetition of history. It concludes with an eerie interpretation of ceremonial, traditional music as, if not only to honor and guide the ghost of the prisoner but those of the Losheng victims as well.

Each part of the film was originally designed as a separate installation piece, but often the films are screened in a more traditional setting as well. However, in this case usually not all parts are shown, and the selection can differ. The reason for this is understandable as the film hardly has any dialogue and some parts are even entirely silent. This can make it hard to watch all 100 minutes in a cinema where the viewer does not have the liberty to switch between the films that he has in a gallery setting. But at the same time, the cinema setting makes it much easier to open up his work to a larger audience.

In the title “Realm of Reverberations” reverberations points to the prolonging of a sound, but it can also mean a continuing effect, and in this case, both those meanings apply. Since Chen Chieh-jen only got involved with the Losheng Preservation Movement after 2008, the films don't focus on the demolition itself, but on the effects both the sanatorium and the eviction had on the people involved. At the same time, by making these films, he prolonged the memory of Losheng Sanatorium and kept it alive.

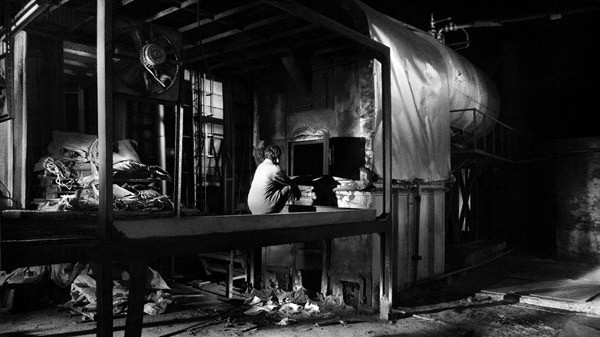

The sound design stands out. It is sparse with no dialogue, only the occasional voice over and apart from two songs and the end sequence there is no music in the film at all. Large parts of the movies are silent and although there is the occasional diegetic sound, the noises made by distant trains mixed with static and of the wind blowing through the ruins dominate the soundscape and add a sinister feeling to the film.

Chen Chieh-jen 's background as an artist in photography and performance art plays an obvious role in the visual conception of this documentary. The shots of the ruins are stunning and meticulously staged and lighted, very little happens in them evoking the idea of looking at a photograph. Throughout the film, these scenes are interwoven with archival pictures and short performances, such as former nurses singing or the young woman sorting papers. They too are staged, and it leaves wondering how much of this is scripted and how much is improvised and if, for some scenes, actors are used.

The approach Chen Chieh-jen takes in “Realm of Reverberations” is an interesting one. The emotions and impact Losheng Sanatorium had on the people portrayed can be felt by the viewer, but, without some context, the details of their stories are not always clear and certain subtleties can be lost to the viewer. That is a shame because the film offers many layers of information for interpretation and contemplation. Although “Realm of Reverberations” might lend itself better to a screening in a gallery than a cinema the amazing imagery make that this is a film that needs to be watched on a decent-sized screen so every chance to see it properly projected is one to grasp.