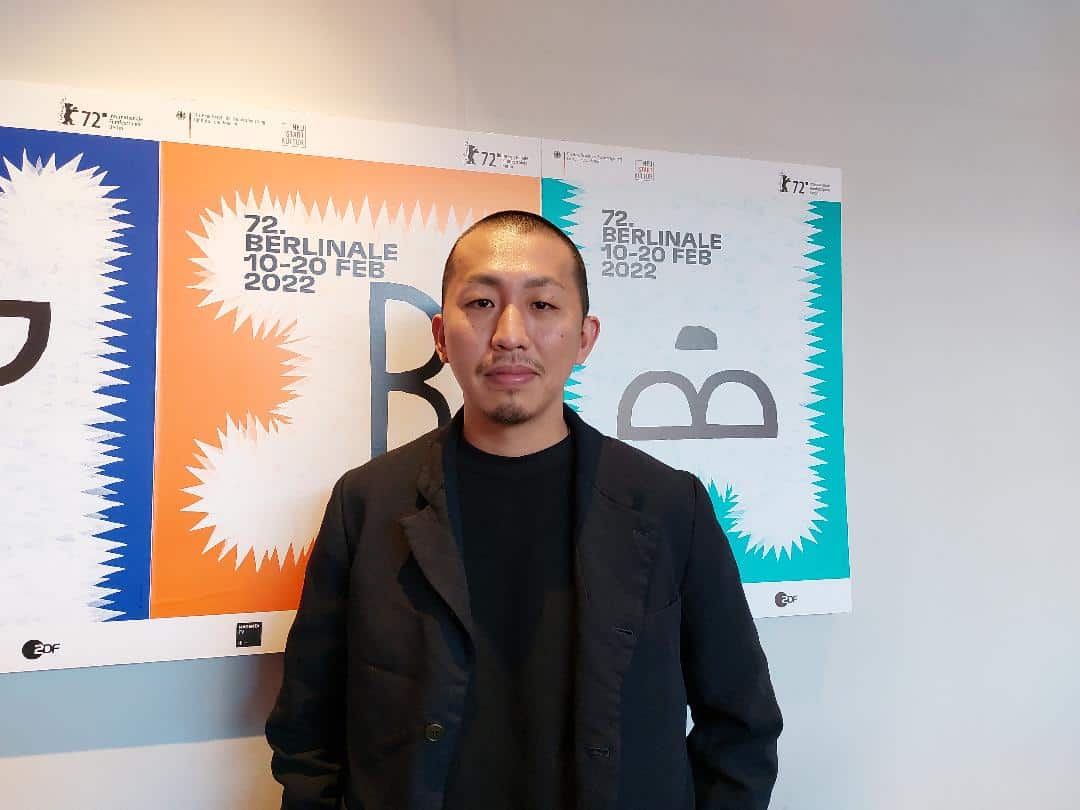

Chen Chieh-jen was born in 1960 in Taoyuan, a village for veterans of Chiang Kai-shek's army which retreated to Taiwan after its definitive defeat by the Communist army. He himself is the son of a veteran. He grew up during the period of Martial Law (1950-1987) and the so-called White Terror which began after the 28 February 1947 Incident and continued until the beginning of the 1980s, during which time an enormous but imprecise number of people opposing Chiang's regime were murdered or imprisoned for long periods of time.

Chen lived in the district where both the Martial Court and the Xindian Martial Prison were situated. In the 1980s, he challenged the limits of expression under the Martial Law system and the conservative art establishment with guerrilla-style performance art and underground exhibitions. In 1996, Chen created a series of photographic and video projects that re-imagine, re-write and re-connect his experience of living in a marginalized region.

He has consistently experimented with community formation, integrating other participants with his film crew. This has conferred an activist quality in his creative process, one that is directed at re-envisioning society.

We sat with him on the occasion of the Taiwan Film Festival March showcase and talked about his “method” with his non-professional actors, the power of silent, the place and space in his films and more.

Some of the questions were from our Nancy Fornoville, who couldn't attend in person.

You have a background in photography and performance art; how and when did video become your preferred medium?

I actually started when I was very young to use moving images, my first piece in the 80s, but then I really started again to use the video in 2002. Take “Factory” as an example. In 2002 for my film “Lingchi: Echoes of a Historical Photograph” people all gathered together in a factory, they had all lost their jobs as it had shut down in August, and these female factory workers self-gathered and helped me to make the film “Lingchi”; but then in 2002, I spent some time with them because the factory had shut down without notice resulting in them suddenly losing their jobs.

At that time, I decided I was going to make a film about them but I didn't do it straight away, it took me 10 months. I stayed next to them, I was around, without carrying a camera, just being near them and gradually I told them. I didn't have a budget initially but 10 months later I could tell them: “I have a bit of budget and I think we can make a film”. When I told them, they self-gathered to help me to do a pre-production and to call the people who also had lost their jobs to come back and help me and I paid them with the budget I had found. Besides them, the only professional crew was the cinematographer, the gaffer and my brother, so the rest was organised by them.

“Realm of Reverberations” is made of different segments, some features the patients and the workers, others feature a character's monologue. Is she an actress or are the lines written by you?

That lady is a very special and spiritual person, her emotions are very real. During all the years she took care of the patients and saw many coming and passing away; she gathered all these emotions in her, carrying them on herself. On the day we asked her to do the scene in the bed where she is slowly tiding and cleaning the bed she just couldn't stop crying. We let her gather the emotions and let them gradually come up and let the camera roll. It took the whole day for only that scene, so maybe you thought she was acting just due to that very condensed emotion being very dramatic.

Very natural, I didn't really think she was an actress but maybe that you had written the lines .

Actually I've never used professional actors … yet … (he laughs)

You can see all the portraits of the patients she had been taking care of. She had been taking care of them for a long time and she had feelings for them. Not only was she taking care of them but she also made drawings of the patients and residents and also documented all these people and wrote diaries. All her notes and all the paintings and drawings are still there and I actually used some of the writing from her diaries. In fact, her monologue comes from all the notes she wrote, so it's actually her “voice”. In this sequence she says she could hear the sounds of the people protesting outside and she accompanied the patients to watch them, she was crying and everything became foggy.

I want to show you some clips. They are actually clips from “A Field of Non Field”, but related to the way I work with the people.

These women you have just seen are like the female workers of “Factory”, but a different group, they have been protesting even longer than the “Factory” women about the sudden closure of their workplace. So I asked them: “Can you come up with one sentence to describe yourselves in these past 20 years?” And they came up with “Nameless, what can we do?” and they kept repeating it. As I was about to shoot, all the workers started to rehearse and repeat this line, one after the other they all started to cry and to hug each other and comfort each other and some started to sing a song, a happy song. So, it started as a trigger to make everybody emotional. This is how I work with people, they all have their own stories, they have a very rich life experience so after the rehearsal I don't need to over-prepare them.

So, going back to the young lady in “Realm of Reverberations”, we didn't prepare everything for the film, but I wanted to show her, because I'd read all her notes. Even though many people have joined the protest, those who actually take care of the patients are only two and she was one of them. She is the most immersed in this situation, most of the patients she was taking care of are residents of this quarantine place, many people gradually passed away, almost everyone.

Yes, she says in the film she couldn't bare it any more.

She also collected lots of documents on this virus, she was actually very young when she started to be part of this movement. She felt she was really committed to this patient (who she mentions in the film) and she wanted to take care of him even more; when I met her she told me she was thinking she wasn't able to leave. Through filming her it's a bit like her sorrow came up again, could be re-imagined gradually. That is why I spent one whole day for just that one scene of her tiding up the place. Because she needed to have this ritual, she needed someone to allow her to let out everything and cry until there were no more tears, so then she could actually be free.

So after we finished filming she was able to go back to school and restart her life, even if she still takes care of the patients. So maybe when people are watching this scene, they find it very dramatic but what I did is to give her the space so that she could do her ritual.

I found it very interesting that the lady in the movie was obsessed with the idea of creating a Museum of Losheng Sanatorium, while your movie for me is actually a sort of emotional museum of Losheng.

Yes. Actually many people wanted to make a museum of Losheng, but when they started to think it got overly complex and they found out they couldn't. It's complicated to collect all the things to make a museum because many people have many different ways to look at it, so when this happened many people had chats with me and I told them: “Maybe instead of building or setting up a solid museum we can have something more open, more organic and more fluid so that it continues to grow, because individual views are also part of a museum, are as valuable as emotions and stories.”

Some of your films are silent, is it a functional choice, related to the needs of the medium (installation) and if not, what is the reasoning behind this decision?

Again with regards to “Factory”, many of these women, factory workers had been protesting for many years, some of them even a decade, many of them had occupied highways or lied on the rail tracks for that purpose. However, many years later nothing had changed and they just felt like no matter how much they say, nobody listens to them, so when I went to talk to them asking to make a film about it, they said: “Yes, of course but can we be silent in the movie?” So, in that case it was actually requested by the factory workers and in the end that actually made their voices louder, so I decided to leave “Factory” silent.

Even in “The Route” the silence of the protesters is very “loud” and powerful and it looks like you've used the past to convey a message of solidarity to the future.

When I was making “The Route” I was actually thinking “What if?” In reality that event already happened, it is already in the past, but I was thinking “What if it has never finished?” That was my motivation because in 1996 the harbour workers in Liverpool held a protest but actually even in Taiwan in 1996 the workers were protesting and so my question, my link was, “what if”. Because all these three films relate to labour movement and I started this silence mode in “Factory” and because I found it so powerful, I also used it in all the three films related to the movement (“Factory” 2003, “The Route” 2006, “Bade Area” 2005)

Space and place seem to be very important for you; buildings like factories, ports, sanatoriums are predominant in your work, and people look more like ghosts

“Factory”, again, is a good example as the factory itself is a place of manufacturing and production so what happened is that when it shut down and the people lost their jobs, the spirit of the building was still present there because even if you don't see anything that directly represents capitalism, it is still a space that was there to manufacture all the things that make money.

(He draws a square, on the table) This is the factory, and this is the gate around it; when I decided to make this film, only two or three people gathered, because there was a 6-year gap between the factory's shut down and the protest. They had actually closed the factory and put up a picket line; all the bosses had already gone. At the beginning of the protest, many of the news journalists came to report the events but because it had been 6 years, nobody cared by then anymore; so when I was there for 10 months I would sit with them and do some little work in exchange for money. It was a really weird feeling for me, almost like we were protesting next to this emptiness, this building that had already been emptied and nobody was there.The landlord had actually hired guards to prevent them from entering and occupying. I had a conversation with a security guard and he allowed me to go in and have a look. I spent 10 months there, there was no electricity or water but a great thing was the air. As I spent all days and nights, I breathed it in, I felt this air had been preserved for 7 years, all the dust and the smells were 7 years old. All the calendars and the props were from 7 years before too.

I had enough time, lots of time to spend in this building myself, so after 10 months, I cell-phoned them the budget and I finally gathered the money to make this film, so then I went around to gather the other workers to come back and we set a corner of this factory to the way it used to be so we started to work. We opened the factory in this corner but facing the huge emptiness and we started to come to work, check in – check out, clock in-clock out, all these people started their routine of the work they used to do.

So, to come back to your question about the places and the relationship with the buildings, even though it is abandoned, the land of the building is still worth a lot of money and it's a space and place that still represents capitalism and ownership. But at the same time this place is also owned by all these female workers because they have spent 20 years working there so they also own these parts of the memories of the space, even though it has been abandoned and empty.

So it's a place and space of capitalism but also a place and space of the women's memories. And there is also a third aspect of this space that is the emptiness. As it was abandoned for many years, the smell of the dust and the moldy air represent the life of the empty building. Filming lasted only five days and in those five days, all the three layers of space merged together, the capitalism, the memories and the “abandoned-ness”, they all combined together. It's not just a ruin.

When I started filming, the landlord wanted to come and see what was going on, but the security guards told him: “Oh no, you should stay away because they have re-organised the protest and you could be in trouble!” So, the guards helped us to keep him away.

Your films are very political, don't you think that being shown as installations in art places could restrict their circulation?

To premier my work I go back where I filmed it, to the real location, and do a screening there, so for me to make a film or a video is a whole collective thing. From the beginning, we organise everybody to gather and then we discuss making the film together. We start filming, then we premiere on the film location and then we bring the work to galleries, museums or any other place we can, so the whole thing from the beginning has a dynamic movement, like a ritual for projection.

All of my works always have this ritual of the first projection on location, and after that they are like ghosts, they can go to art galleries, to museums, they can go to cinemas, they have their own life. It is a proper ritual, after that they are free spirits, they have their life and will wonder around the world in different locations.

I noticed that in “Wind Songs” , which shows the screening of “Realm of Reverberations”, you indulge on the portraits of the viewers, watching their reactions.

Yes, I tried to catch all the faces there. At the time, digital technology wasn't so advanced so it's not perfect but I tried. While observing the audience watching the screening, you can actually see three types of audiences. The first type also has tears in their eyes and it's the people that had participated to the preservation movement, on the contrary there is the group of patients that are very relaxed, and the third group is composed by young people that never participated in the protest or never knew about these stories and it is very interesting to see that they don't know how to engage with what they are experiencing. On the other hand, the first group get very emotional because they can see themselves in their past youth. That is why I took those individual shots of the audiences

Are you working on something at the moment?

My latest work is dated back to 2017 because I spent too much money on that (laughs), but I am organising a fundraiser for my next project.