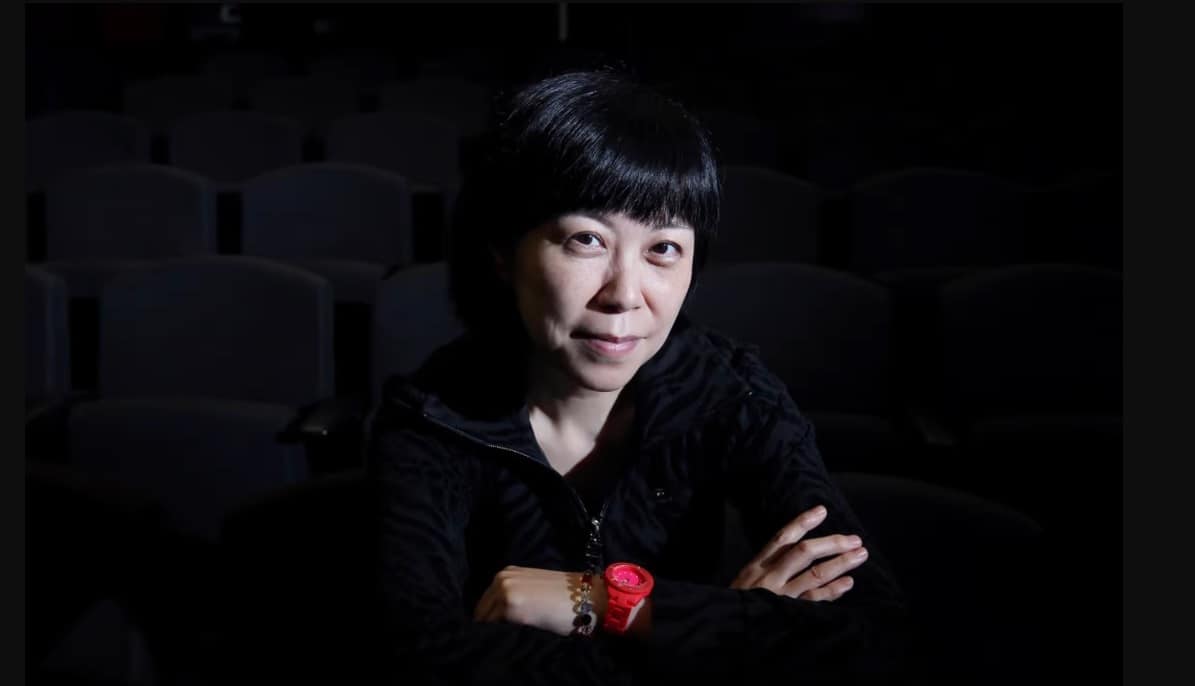

Lester Chit-man Chan is a Hong Kong actor and director who has collaborated with many famous directors, of the likes of Ang Lee, Tony Chan and Julia Kwan. After a long career, Chan has decided to make his directing debut with “Apart“, a feature about a young couple in the midst of socio-political upheavals in Hong Kong society. The film was also screened as part of this year's Osaka Film Festival.

We talk with him about the inspiration for the film, its political and social context as well as the creation of the characters of the film.

“Apart” screened at Osaka Asian Film Festival 2020

What was the inspiration for “Apart”?

“Apart” was originally conceived as a love story exploring the cultural identity and differences of the younger generation of Hong Kong – those born before or after the change of sovereignty in 1997, and growing up under its influence.

It originated in the winter of 2013 when I had a reunion with some old-time friends from high school. One of them “disappeared” after moving to the U.S. for university and then staying for work and immigration. All of a sudden, he showed up with his daughter – a grown-up young lady. A happy surprise indeed. And his cute beautiful daughter complained about her daddy's speaking Cantonese, our native tongue, only when he scolded her, making her not so conversant in Cantonese except for bad language – all in American English.

This reminded me of my own experience when I was studying and working as an actor in the U.S. East Coast. Though I chose not to stay, these ideas about culture were familiar to me. As Hong Kong is a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural society in its own way, there is a broad variety of young people with different ethnicities and very different experiences growing up too.

This led me to start writing a love story between a locally-grown young kid, and an American-Chinese girl born in Hong Kong but raised in the U.S. The central couple soon evolved into a group of four young people as seen now in “Apart”. But as the urge for realizing Hong Kong's promised democracy became stronger and stronger in 2014, and students' leading role became more and more prominent, I started to ask myself, “What if the characters I've created are real, how will they respond to today's Hong Kong?” This helped me find a much stronger focus on their love, relationship and personal development. And the script was re-written with the senior students (Maryanne and Yin) replacing the freshmen (Jessica and Toh) as protagonists.

One more character I've always wanted to add is from an important ethnic minority, the Southern Asians, who are locally born, and full-fledged Hongkongers with complete fluency in Cantonese. But due to specific difficulties in the casting process, I finally switched to another important minority group – new immigrants coming to Hong Kong only during their late childhood or early teenage years (Shi), leaving some traces of their mother tongue. Personally, I've had acting students from this background, and I've always found their experience and stories intriguing.

And then, by the time I had funding from the First Feature Film Initiative to shoot “Apart”, it was already 2016, two years after the Umbrella Movement. And as the post-production took me into 2019 unexpectedly, my sense of keeping the story in the present tense naturally asked me to rewrite and refine it along the way with post-Umbrella Movement events as the backdrop. Finally, the unexpected eruption of the Anti-Extradition Movement also gave me a precise timestamp to end the story in June 2019, instead of a more generic “a few years later when they meet again…”.

How did you experience events such as the protests surrounding the Extradition Bill, which are also depicted in the film?

Though I am not a social activist, I do pay due attention to socio-political developments. The Extradition Bill Amendment allowing Communist China to grab anyone in Hong Kong across the border “legally” posed a huge threat to the current way of life of Hong Kong – and much so for artistic and cultural workers. I was drawn to this possible change in spring of 2019 through the advocate of some pro-democracy activists, and joined the peaceful demonstration in April. There were then 10,000+ people. Later, as the events unfolded, I joined the 1.3 million people march on June 9, and 2-million-plus-one people march on June 16, due to the harsh and non-responsive attitude of the Hong Kong Government. Since then, I have actively followed many of the events and developments, mainly through social media.

To me, this Extradition Bill incident is stepping across Hongkongers' final bottom-line – that our way of life cannot continue without democracy. So it is not surprising to see such a huge resistance from all walks of life and so many people involved – young people in particular as they are the most worried of the uncertainties surrounding 2047, the year when the currently-promised system – despite only partially fulfilled – is to end.

Your film repeatedly hints at a growing chasm within Chinese society, especially between the younger and the older generation. What do you think about this particular generational gap?

Perhaps in a much longer timeline, the entire Chinese society will still be in a continuum of change or evolution. Back in the beginning of the 20th Century, the Ching Dynasty was overthrown and China had the first republic in Asia. But perhaps this advancement was a mere short-lived mirage, not strong and lasting enough to counter the thousand-years-old tradition of dynasties. I once heard a historian saying that Communist China is a mere backlash to revolution, pulling China back to yet another dynasty though in the name and disguise of so-called communism.

Whatever the truth is, generation gaps exist. In a changing society with strong conservative forces from both the privileged and the nostalgic, however, the inertia or resistance to new ideas and changes got to be huge. Generation gaps thus expands to cover not only the difference between ages, but also the difference between privileged and non-privileged, those seeking changes and those resisting them, etc.

And in an even broader perspective, Hong Kong has already advanced into a modern world under the protection of the British rule, way before Mainland China even had a slimmest chance of doing so. This might perhaps be also perceived as some kind of generation gap between two places and two systems.

What do you think about the current developments within Chinese society?

This is a huge topic and deserves many pieces of dissertation. But some basics should hold. For example, one slogan “Hong Kong is not China”. This still is, despite the very efforts of both the Chinese and the puppet-Hong Kong Governments twisting it. In its ideal state, the soul of a society should be its people, not its government. This is still so in Hong Kong – at least to a certain degree – despite the authorities led by kowtowing officials submitting to Beijing's undue directions or influences. For the majority of the people, the main argument is on how much to submit or resist such undue influence – also reflected in the dilemma of the characters in “Apart”, such as Yin. Only a minority will choose everything Beijing wants, despite they themselves still “prefer” to live in Hong Kong, not in Mainland China.

As to the Mainland, I suppose the situation is kind of simple yet complex. The thousand-year-dynasty tradition has a deep-rooted influence in many people's minds, including those ruling and those being ruled. The current situation may perhaps be exemplified as a pressure boiler, I may say. Pressure or conflicts build up here and there, without stop. Without a due political process to resolve them, however, the solution is often higher pressure coupled with stronger lock-up of the lids. There are certainly people with an independent mindset, but the so-called communist government's response is to “unify” or cleanse people's mind and thoughts with propaganda and censored/ fabricated information.

In this way, deep-rooted and unsurfaced conflicts often go unnoticed until the moment of outbreak, just like the recent Wuhan virus. By first deceiving the people (and indirectly the world), my observation is that the Chinese government believed that they could contain it without scaring everyone. But as they failed, drastic measures disregarding people's lives (and of course their rights) topped with lies were introduced for society's “greater good”. And if anyone showed any discontent, they would be treated “as individually as possible” to stop small bubbles coalescing into bigger ones. But if that failed too, then a real big bubble – or trouble – would explode. This happened many many times throughout Chinese history, causing violent revolts and bloodshed. No one knows when this will happen again. But as there's no material difference in the strategy taken by this so-called communist government from all previous dynasties, it's not unreasonable to assume a somewhat similar outcome when it collapses.

Anyway, is this ruling class real revolutionaries from the outset, or merely a group of revolters grabbing power and repeating the same cycle of up-and-down power? It takes historians and scholars to answer such questions though.

How did you come up with the interesting structure of the film, especially with regards to the time jumps?

“Apart” was originally written in a highly parallel form, with the present-tense story going side by side with the few-years-ago story. But as the rough cut was assembled, we found it too disturbing and too difficult to focus. Various structural forms were then tested with not only the editing team's own input but also a number of focus groups' feedback. At one point, we even settled with a wholly linear approach whereby the story unfolds chronologically. But as the script was never written this way, I did not find it satisfying although some focus groups seemed to like it.

Thus, despite for a few times we were about to lock the editing, I kept breaking it apart to try finding the best structure for this story. It was towards a rather late stage that I finally settled with the present structure. This partly explains why the post-production took much longer than I had originally expected – although it also gave me a happy surprise to effectively include the 2019 incidents into the time-space of the film.

Can you tell us something about the creation of the characters of Yin and Maryanne as well as the collaboration with your cast?

Most writers borrow something from their lives when writing. For me, the characters of Yin and Maryanne do have some traces from myself and an ex-girlfriend of mine. Though their personalities, family backgrounds, and choices are of no direct resemblance, there are reasons to make Yin an engineer, and Maryanne a lawyer.

The critical dilemma of Yin is his simultaneous desire to create a business out of his own knowledge and interest, as well as to attain democracy. For his creative business to prosper, a “more stable” (status quo) environment in Hong Kong – and access to the Mainland Chinese market – are important. This he should have learnt from the life examples of his father (though they don't get along very well) and through his own observations in the Umbrella Movement. It's not that he's given up on democracy, but Yin's dilemma is a universal one amongst Hongkongers who “also want” good business opportunities in China.

For Maryanne, however, with her family being refugees running away from the Communist rule, her desire to protect Hong Kong's way of life from Communist China's influence through democracy is simpler, stronger, and more straight-forward. Also, for her profession, whether she gets into politics or not, she could have a bigger space to not directly consider the “Chinese factor”. Thus, these set-ups have helped to amplify their commons and differences, which would lead to repeated conflicts as they weather through their life and relationship.

In order to bridge the gaps between my young actors' personal life experiences and those of the characters, I specifically required them to attend a three-week training workshop without absence. This included basic acting classes co-led by an acting coach and me, and rehearsal of all major scenes. No matter what their previous experience were, the training helped tune them to the same starting point. In the least, it helped build up their genuine friendship, much improving their non-verbal performance, relationship, and body language, during shooting.

So far, what has been the response to your film, especially in your home country?

“Apart” premiered in the Hong Kong Independent Film Festival 2020 in January as a preview of the film, as it is not yet released commercially. The Festival added three screenings after the original screening got a full house.

From the Q&A afterwards, my feeling was that the audience was generally positive about seeing the reality of (and asking questions about) Hong Kong as depicted in “Apart”. One very encouraging audience even compared it with “Doctor Zhivago”. But there were also a few voices showing their discontent, mainly about the social movements not more fully explored or depicted in the film. And I had to re-iterate that my creative focus on the characters rather the movements. In any case, it's not easy if not impossible to fulfill all expectations, and I know I had already made a clear and conscious choice from the outset.

Can you tell us something about projects you are currently working on?

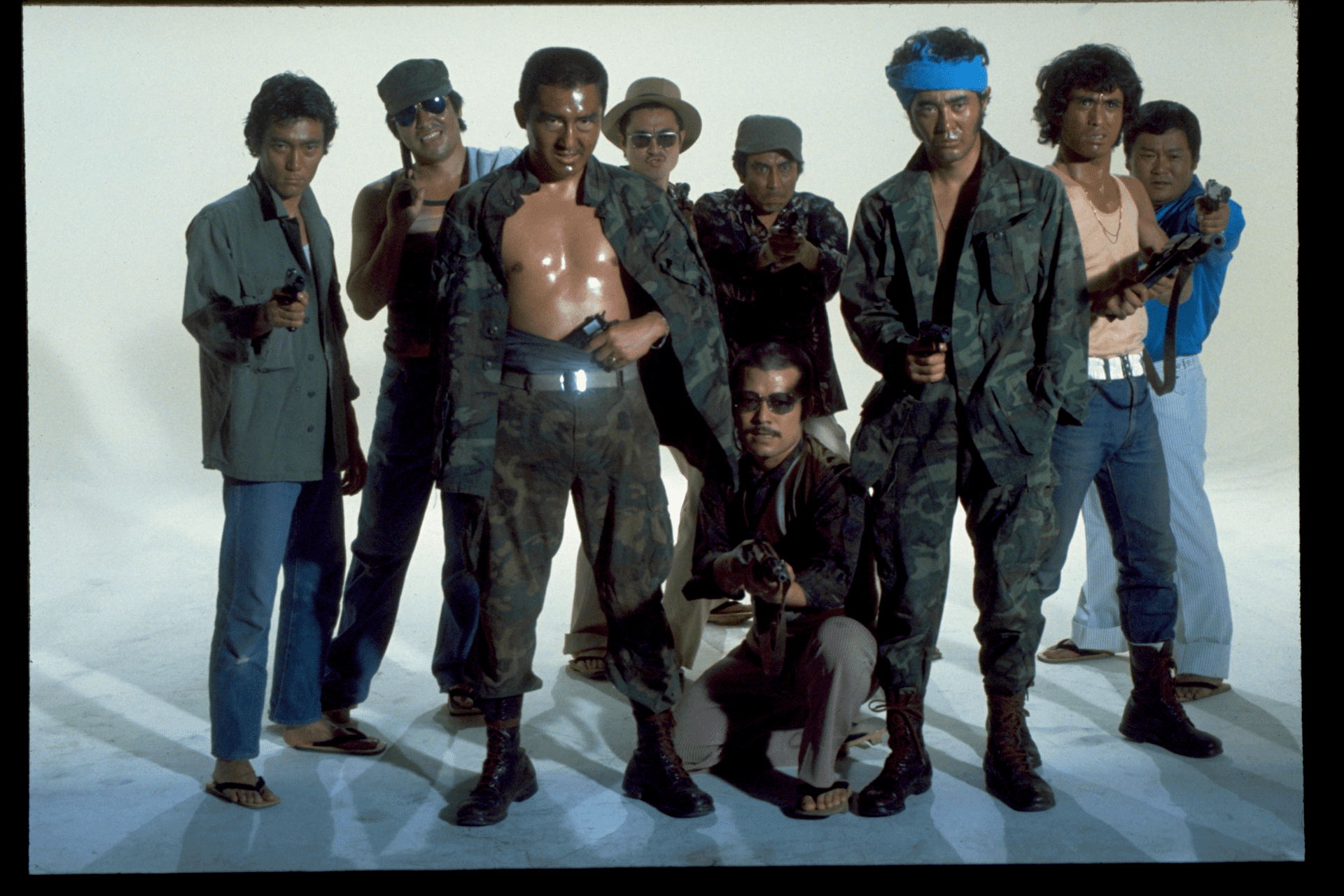

Currently, I have two film projects hopefully to bring into production. One has a draft script but will need more rewriting. It's about a boy looking for his father in a critical period of Hong Kong's history, the 1967-riot, whence the local communists challenged the British rule but were finally cracked down, leaving Hongkongers to live the way they like.

The other is an adaptation of a memoir of which I have got its author's authorization. It happens in the early 1970s, another critical period in which Hong Kong recovered from her previous political crisis, and the modern Hong Kong began to emerge. The story is really about education, in which some crude untamed youths with heat and passion found themselves slowly transforming into more sophisticated souls and future elites of the society.