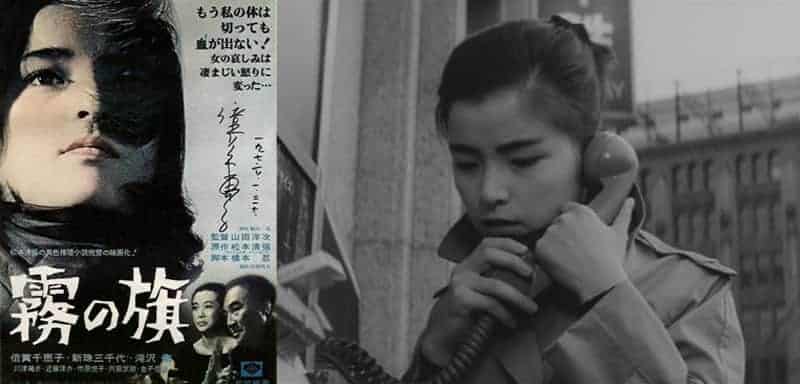

I first came to know Seicho Matsumoto when Adelphi Edizioni published an Italian translation of his 1961 “La ragazza del Kyushu” / “Pro Bono” (Kiri no Hata), and I was immediately sucked into his world of fictional crimes and intricate psychological plots. Wanting for more, I was shocked to discover that despite being one of the most famous and prolific Japanese novelists – often called the Simenon of Japan – only a handful of books where translated in Italian, French and Spanish and – disappointingly – even less in English. Needless to say, I resulted in reading them all during the course of a holiday and I was left rather unsatisfied by the shortage of more.

Buy This Title

Self-taught and of humble origins, Matsumoto (born 1909) started writing relatively late in life, in his forties, probably because during the Second World War, Japanese government censors banned detective novels, declaring them unpatriotic, and his 450-piece body of work includes not only many crime novels like “Inspector Imanishi Investigates” (Suna no Utsuwa, 1961), “A Quiet Place” (Kikanakatta Basho, 1971) – just to mention some of the translated ones – but also ancient and contemporary historical fiction and non-fiction books. He managed to enjoy in full his celebrity status in the 80s and kept working until his departure in 1992.

A young couple is found dead in a rocky cove of Hakata bay, on the island of Kyushu. Their composed bodies, laying close to each other, and traces of cyanide strongly suggest a “suicide of love” and the case is swiftly dismissed by the Fukuoka police. However, local seasoned investigator Torigai Jūtarō is not completely convinced. The two lovers arrived with the same train from Tokyo, but the man, ministry official Sayama Ken'ichi, stayed five days in a hotel on his own, waiting for a phone call, before moving out in a rush, leaving behind a suitcase. Moreover, the whereabouts of the young woman, a beautiful bar escort called Otoki, are rather blurry in the days before the suicide. Not least, nobody knew about their relationship, nobody had ever seen them together. Too many obscure points are not connected by logic lines! Fortunately, even Torigai's young Tokyo colleague, Mihara Kiichi, is tormented by doubts about this case and he is happy to join the investigation. Together, from two corners of Japan, they start to meticulously re-trace the inconsistent movements of the two victims, armed only with their exceptional intuition, their inborn stubbornness and a railway timetable. Is a major corruption scandal linked to Sayama's death? Why does the receipt of a single dinner on the train journey of the two lovers feels so wrong? And who could possibly conceive such a seemingly flawless machination based on perfect synchronicity?

“Points and lines” is often referred as Seicho Matsumoto's masterpiece and a classic of Japanese crime fiction. It is indeed a masterfully plotted intrigue and it includes all the beloved themes and topics of the author, a sort of perfect compendium of Matsumoto's paradigms. However, the ingenious ploy alone would be just a clever divertissement, but “Points and lines” is also a great example of his insight into human psychology and ability in creating multidimensional characters, complex motives and mundane, yet profoundly humane and intuitive investigators. His crime fictions are, for their intricate psychological, almost of Hitchcockian nature, very cinematic. In fact, several have been turned into films. He collaborated on adaptations of his novels to films with director Yoshitaro Nomura, who directed 5 of them, including Zero Focus (Zero no Shoten) in 1961, scripted by Yoji Yamada and also recently re-made in 2009. Yoji Yamada went on directing “Kiri no Hata” (“Pro Bono”, A.K.A. “Flag in the Mist”) in 1965.

Like “Points and lines”, several of Matsumoto's stories start with an apparent non-crime, a suicide or a natural death, and the author takes his pleasure in dismantling, in a reverse fashion, the whole construct of what would have been the “perfect crime” if it wasn't for the incredible deductive powers and dedication of the protagonist. Following this digging work is the real pleasure of Matsumoto's books. Don't expect shock endings or unpredictable twists, as you would be disappointed. This is partly due to the fact that some of his books, like “Inspector Imanishi Investigates” had started as serialised fiction, then re-edited into books. However, it is the journey and the process that enchant and constitute the real treat, behind the detailed police procedural.

Torigai Jutaro, the old Fukuoka cop, seems to be a preparation for Matsumoto's best-known investigator, Imanishi, who will make his appearance in 1961, in “Inspector Imanishi Investigates” (Suna no Utsuwa). Imanishi is a humble man, devoted to his family, who likes his cigarettes and his bonsai trees. A slight resemblance with Inspector Maigret must have been the reason why Matsumoto is compared to Simenon, but – anecdotes on a side – he indeed established the genre, not seen before in Japan, of the ‘social detective story'. In fact, the writer's left-wing socialist faith influenced his realistic portrayal of Japanese society and his concern for ordinary people; he often exposed the bias of justice – like in the bitter plot of “Pro Bono” – and the corruption among government officials.

The railway system, pride and joy of Japan, is a key element in “Points and Lines” and Matsumoto turns something as dry as a train timetable into a poetic way of traveling with the fantasy. It is worth having a map of Japan at hand as the characters keep moving back and forward and keeping up with their movements is essential to the story and part of the fun. Trains and a scrupulous knowledge of geography and regional dialects are always components of the author's novels, even when not a functional element of the plot. His native district of Fukuoka, Kyushu, is often present and juxtaposed to Tokyo, probably as an affectionate homage to his own geographic and social migration.

Matsumoto's talent in comprehending the human psyche and in giving social context to the crime itself, makes it a compelling and entertaining reading and a very authentic portrait of post-war and 60's Japan society.