By Nicholas Poly

After three massively successful collaborations in every single artistic (and not only) aspect, the collaboration led by Hiroshi Teshigahara, Kobo Abe & Toru Takemitsu came to what's meant to be its final installment. This happens while the still hot and vividly ‘redish' summer of 1968 takes place and through the release of the not so renowned title that ‘The Man without a Map' is. Their overall collaboration has already bloomed within a precise time frame of almost 6 years (which translates as an exact 2 year gap between every film). Abe's novels for ‘Woman in The Dunes', ‘The Face of Another' and ‘The Man without A Map' along with ‘Pitfall's screenplay were usually published almost a year before the shooting, followed by his theatrical adaptation. As a result, Teshigahara and cinematographer Akira Uehara, along with the visionary avant–garde composer Toru Takemitsu, the crucial link between the first two artists (accompanied by a team of alike, truly prolific, fresh minds) breathe cinematic life into the aforementioned scripts. I will not get into various personal background details. I believe a proper writing dedicated separately to each one of these truly multidimensional artists would serve the absolute justice they deserve. Therefore I'm going to get straight to the chase.

During 1967, Abe publishes ‘The Ruined Map'. By then, Abe is known in Japan for his versatile style in playwriting. He is also known for his philosophical quests and his common character forms, which come pretty close to the Kafka – Ionesco – Beckett triangle coated with hints of Mayakovsky's poetic radicalism, among many other influences. In this case, Abe creates what appears to be, at first glance, a detective-mystery novel that steadily spirals in deadpan existentialism and identity crisis. The searcher becomes the lost one. Faces approach as easily as they vanish. Facts which seem to matter with a naked eye become less important as they end up mixing into the depths of human psychology, within the backdrop of the post modern Japanese urban landscape. More precisely, the urban environment seems to have a full part of its own and quite a vivid one. As a result, this triggers Teshigahara's visual interpretations, which are brought onscreen in a profoundly poetic manner. Even though, in this particular case the vision seems a bit more austere, Teshigahara succeeds in presenting facts, figures and places covered in a dreamlike veil, but without losing touch with the problematic reality. This takes place built on solid, existential foundations, which Abe's characters possess. He achieves an almost unique resonance among the human factor, the artificial background and the natural environment, in quite a special way.

Names and faces do not matter so much as identities and figures blur between space and time like some kind of mirrored images. Figures like thoughts reflect their presence on the environment.

“What were you looking at?”

“A window.”

“No, no. I mean what were you looking at through the window?”

“Windows… lots of windows. One by one the lights are going off. That's the only instant you really know somebody's there.”

It's the inner psychology followed by the responsibility either the irrationality along with the consequences that thoughts and actions encrypt. This is a fact which brings us closer to the very core of this work: the path towards a modernist reality led by our primitive needs and instincts or even against them. Personal space falls across the landscape and as time progresses, characters become unaware of what is going to follow. In my opinion, Abe imposes the question of whether we can live one and only life surrounded by different perceptions concerning one certain single fact. Therefore, it needs to be stressed that his work inhabits in metaphysical territories and as a result, the cinematic dramatization is helping these elements to become more visible, but without subsiding the true existential value of his characters. In this particular work, it's the physical disappearance of one person and what's left behind: a name, a photograph and an everyday item which becomes the proof that someone left a trace. In our case, this is a matchbox. But is this the true identity of oneself, the fact that we may have one identity. And how many personalities we happen to project? What exactly others perceive and what we intend to claim as an identity? Maybe, even better, what is the effect caused during our time of presence and throughout our absence on those who are within our point of reach? In my humble opinion, even Abe himself is having difficulties to deliver a straight answer. But without a doubt, he doesn't intend on dropping his case, he's willing to explore. He will follow his main character. He shows confidence in trusting his instinct.

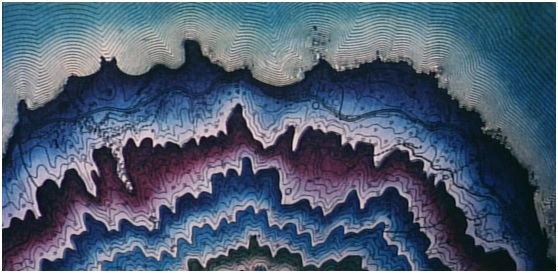

This is Teshigahra's first film in color and color is everywhere, either in primary or saturated form in very particular sequences. This happens especially when he needs to stress that the investigator is losing his sense of direction through space and time, and his confusion, along with the mixed perception of facts. He recruits Kiyoshi Awazu to design the titles, one of the most respectively creative graphic designers to come out of Japan. A real genius and a formless mind with tremendous sense of composing surreal asymmetrical shapes and transforming them into extraordinary designs, and amazing knowledge in color palettes. Awazu is admired for his wonderful urban and film poster designs.

(I lay these links here in case anyone wants to check out a few more things about this truly gifted designer and some of his work: https://gr.pinterest.com/pospag/poster-japan-kiyoshi-awazu/, http://neojaponisme.com/2012/12/11/glue-vapors-go-the-life-of-awazu-kiyoshi/ ).

The opening frame is a saturated overview of the urban landscape where our story takes place. The image resembles a map overview, but looks like a mere hallucination. Teshigahara slowly lands the frame onto a highway filled with car traffic. In the same time we can listen in a voice over the apparent victim's wife voice. She's revealing the identity of her missing husband, the reason our main character, a professional detective is being recruited on behalf of a private investigating agency. This happens in order to trace the missing ‘footprints' of an oil company manager who vanished into thin air.

As the camera's landing we enter a coffee bar named ‘Tsubaki's', apparently after its owner. That's where we get to meet the nameless detective, performed by Shintaro Katsu (“Zatoichi”, “Hanzo the Razor”) trying to match information about the person he's holding this investigation. The only kind of evidence he has in his hands is the matchbox we mentioned before, which leads him in this particular place, a photograph, and the identity of the missing person. I believe that Katsu is an ideal pick as the detective. His detached look and dead serious but also quite determined figure, his-most of the time-questionable but empty stare serve as an exquisite vehicle as the -‘descending into a spiral of confusion'-investigator. As the plot thickens and while he becomes aware that through straightforward investigation he's heading for a dead end, his expressions deform and we clearly see a man who's on the verge of a personal breakdown. Another reason I can assume why Katsu was picked by Teshigahara is his incredible performances throughout the Zatoichi movie series. His performance as the legendary blind samurai who's driven by his intuition and instinct to sense every possible threat around him is classic. Katsu managed to bring the difficult task with great credibility and at a reassuring ease, a trait that would help the audience believe in his character even more. That's more or less the case of our central character: he's a drifter making his way through a dark path. This path is not a straight one and he's going to get involved with a number of characters who evidently want to shine a light on the case. Of course, nothing is as it appears to be in the first place.

He has a deadline of one week to proceed with the case. Later on, his agency officially pulls him out of the case. That's when he decides not only to continue this investigation by himself, but he also feels obliged to dig deeper, in order to draw the best possible conclusion. As mentioned before, time is only a scheme to move through space and this is the first part of our story. Since time is cancelled, space almost decomposes, the main character seems to get lost between faces, places and facts. They become one substance. I got the impression that somehow Teshigahara wants us to sink into the modernist urban landscape along with his main character. From this point on he's trying to guide his way through, mostly based on his instinct than using plain investigating procedures. He is driven by the victim's possible well kept secrets or by his apparent actions which come up as habits. In other words, he tries to walk deeper in his shoes. He wants to follow him step by step. Finally the detective ends up getting lost, in a variety of ways. He sees himself entrapped, more like finding himself between two worlds. The one he's in physically, and the one forming through the case. The two worlds blend in a hallucinatory state, a bit toxic, somehow demoralized and with a sense of threat against his own existence.

The odds in trusting the characters that revolve around the missing person are quite a few to zero. A fact that makes the possibility to form a solid case quite difficult, based on the confessions he-anyway-hardly gets. Usually, when it happens, it comes with a personal cost. These surrounding characters are: the missing person's mysterious, almost alcoholic wife; her enigmatic brother who appears quite early and out of nowhere in the film (while in the same way and quite early he steps out of the game); an obviously dysfunctional subordinate-colleague who, as it seems, has some pretty intense psychological-existential issues. There is ‘Tsubaki's owner who's quite unfriendly and apparently mixed with the underworld. There are also a few other female characters like the bar hostess-nude model or the investigator's own wife with whom he's obviously separated but as it seems they still care about each other in a peculiar way.

Etsuko Ichihara as the missing manager's wife

Our hero is patient, he goes through quite a few strange situations, he's smart and apparently he's also experienced. He seems to know how to get his way through facts as they turn up in the first place. As previously mentioned, he doesn't trust anyone except his prime instinct. His assumptions include everyone he meets. But is this enough to finally get him somewhere safe, anywhere near the missing manager's traces or, at last, what really happened to this man and why? Nothing is that simple as Teshigahara's main character is always human at his very core and has weaknesses along with his powers. Thus I comprehend that the key in the missing person's case is given by the actions we watch (either learn) taking place by the people that surrounded him. For instance, in a particular sequence, the subordinate from the oil company calls the investigator in the middle of the night from a telephone booth, in a desperate and hopeless mood. In the previous sequence, we have watched the detective having an interaction with him where he openly calls him a liar over some nude photographs. which the subordinate has under his possession, pointing that they were taken by the missing manager. He confesses his desperation through the phone and then commits suicide while the main character is on the other side of the line. He sounds confused and psychologically broken down. Is this some kind of hint about the missing manager's psychological state and, furthermore, is this scene linked with a possible suicide he may also have committed or was driven to commit? And moreover, did the subordinate blackmailed the missing person with these photographs? Did he end up feeling guilty about something he did? What exactly was the part of this man approaching our main character only to make him a witness in his suicide attempt? Finally, was his behavior driven by his own personal desperation or is there a connection with the investigation…Teshigahara carefully (and constantly) tickles our minds as we move further into the film, revealing small details about each one of his background contact,s but I wouldn't like to go any further that line. We know this isn't the core found in our story. Nevertheless, these mind games are still present within the film, remaining open for anyone to participate in their own will. I assume that Teshigahara's motive is to give us the part of the observer. We end up observing the main observer which is also the main character.

Teshigahara's characters tend to have this characteristic in every single of his films. People are determined for the best, they care, they worry, they wander and they constantly observe and think, but there are quite a few worries which concern them. The law of nature interferes (whether this is a post modern industrial landscape, a village or an isolated desert space) and most certainly it is more powerful than certain aspects of their individual personalities. Abe and Teshigahara have this gift of letting their ‘heroes' loose on interpretations, giving them space to drift, mentally and physically. At parts, they seem static but they are not. They change. We get the impression that the influence of Antonioni, the absolute master of poetic, endless drift is present throughout their cinematic point of reach. I think that one of Antonioni's most riveting masterpieces, ‘Blow up,' shot 2 years earlier has a few things in common with ‘The Man…'. Here we watch a huge variety of shots and even domestic shots create a certain depth. The use of close–ups is limited compared to their previous features, so it's clear they also set limits. That's when the characters get involved with the environment that surrounds them and they get seriously affected. This is brought in the form of some kind of hallucinations that take place within their minds, defying their mental states, but our cinematic reality as well. Subsequently, this is when Teshigahara brings his surreal, avant-garde vision up front.

Another element which is present in Teshigahara's and Abe's approach – also in this particular work – is the sexual tension developed as a motive or as one of the basic instincts within the realm of these characters. In ‘Woman In The Dunes' for example, I get the impression that sexuality is presented in quite a straightforward as much as in a poetic way. This serves perfectly the visual landscape, which is masterfully designed frame by frame by Teshigahara and his team. On the other hand in ‘The Man…' sexuality is a bit of a mixed bag. It works through the story, though. It's almost everywhere but it has evolved into something more complex and the motives are a bit darker. Feelings seem colder with people in the state of confusion. Teshigahara deals with sexual substitutes. As previously mentioned, there is a case of nude photographs, which, to be honest, is a bit hazy about what is going on there. The victim's wife, performed with surgical precision by Etsuko Ichihara, doesn't have a single problem to open her arms after she's taken care the main character's wounds, who, by the way, is investigating the disappearance of her husband. We get the impression of a spider woman who waits for her victims to get vulnerable in order to possess them, but at the same time,she seems so careless. Her-as it seems-brother who has the short but crucial appearance in the case, declares that he is a homosexual involved in a sex trafficking net with young boys and girls. The missing person's colleague has this urge to interact with a bar hostess but he can't, due to financial reasons. I believe these reasons seem more psychological in his case. Each one of the characters has intense sexual instincts present throughout the film, a fact which opens another ‘door' about the not so innocent, but clearly sexually driven turn of the case our main character is into. I can also assume this is a straight comment towards the Japanese society, regarding sexual oppression, which comes as a result of enormous psychological pressure in a amazingly competitive environment on the rise back then.This comment is not presented in a vulgar or exploitative manner, but lots of sexual innuendos point towards it. These elements end up confusing our ‘hero' instead of shining a light on his path. Nevertheless, these facts are presented in a human way so they don't fall out of place. They surely add to the overall frustration. Let's not forget that in 1968, sexual revolution is a really hot topic. There is no way that artists with the cosmic perception of consciousness that Teshigahara and his partners shared wouldn't express their point of view. To be more precise their collective was like a nursery for even more daring minds like Terayama for example, to be nourished.

Takemitsu's wonderful score plays its own part, quite discreetly, but as always it's thoroughly effective. The German symphonic parts are narrowed but always present as they evolve, mixed with ambient vocal parts during the opening titles. There are also melodic parts trying to fit the mood of a ‘film noir'. Then again, the cityscape, which perfectly serves as the sound of confusion, becomes a passage regarding the state that our main character is heading to. The ambience is always evident. Takemitsu is an absolute master of improvisation and he knows how to flip the mood instantly, he knows how to mix his sounds and he definitely knows what Teshigahara needs to deliver through his sequences. His score, along with Uehara's cinematography, truly shine all over the film. I've respectively read opinions about ‘The Man without a Map' which say the big fault of the film is found in the hasty cuts and this is the suffering point of the film, this is why we can't get something equal with ‘Woman in The Dunes'. I don't have the impression that the collective meant to deliver another ‘Woman…'. These jumping cuts, the editing which follows the investigator, sequence after sequence, became one of the reasons why i felt ‘confused' throughout the whole film, almost ‘lost' within the flow. Moreover, I found a reason to believe in this character and why he fell in such a state in the end. It completely worked within my perception. This team knows exactly what to do, they know exactly how to mix their cards, where to blur the boundaries and where to let the pacing a bit loose. The whole mix seems right even if they have to distress us a bit.

Here is a part of the soundtrack composed by Takemitsu:

All I can think is that ‘Man without A Map' is quite a different film from their previous three collaborations. In fact my opinion, is that each of the three previous films has its own personality and this is what happens in this case. Three artists which weren't afraid to experiment with various forms, some more austere, some more ‘open'. The real wonder though, is that they succeed in forming a single body of work in the viewer's mindsets, at least those who appreciate finding themselves in such filmscapes. They become faceless. When we talk about Teshigahara's direction, we read through Abe's thoughts, we listen Takemitsu's avant-garde soundscapes and we definitely watch the characters moving in Uehara's amazingly shot landscapes, practically diving into them, at times losing themselves inside them. This happens through this supposed ‘quadrilogy'. At the same time, they succeed in keeping their individual trademark, their personal vision and first rate skills, which followed them ever after, purely intact. Therefore, I believe this is the meaning of what we may call the quintessence of an artistic collaboration. When artists are bound to achieve such bonds, mostly good things happen, with moments of genuine originality mixed with a number of influences while showing the way to the future. For instance, there are moments we can see expressionism mixing with Noh theatre and Kafkaesque references. We watch cubist compositions and avant-garde techniques blending with the-in depth-examination of human psychology that Bergman and Antonioni mastered in their own unique way and the deeply humanistic but also clinical surrealism Bunuel mastered. All this mix creates such an interesting cinematic universe, which, until today, is dramatically effective, at least for a number of viewers and creators. Moreover, we see their own deeply profound and amazingly creative questions that keep imposing in a variety of backgrounds, but always in touch with what we call human nature. This trait exposes a plethora of human instincts and thoughts within the organized chaos of a modern industrial post war society like the Japanese one was during the 60's. Each one of the great Japanese film masters, writers, poets and painters made their point on this certain issue. This is also an issue which always has been and keeps remaining universal in the end.

The final scene where our ‘hero' is talking to a deformed, run over corpse of an animal on the street is such a masterful one. The man, in a state of full distress, has a monologue in which he is trying to give an identity to something that no longer practically exists. This happens exactly just like the object of his investigation and moreover himself. There's no doubt he went through a transformation. The landscape seems altered, almost like an unidentified threat. The society changed and mankind as well. It was a time things were transforming and humanity was seeking a brand new identity, in most cases more than one. This question was imposed 5 decades ago and I think it remains extremely relevant. Given the chance, by this magnificent closing scene, which sums up as the ending scene of Teshigahara's and his collective's body of work, to describe it with a couple of words, all I can think of is: transcendentally cosmic.