Building a film when almost nothing happens until the finale comes to blow every kind of audience away has been a trait (even if a rare one) of Japanese cinema for many years, probably finding its apogee when Asami stretched that piano wire in Takashi Miike's “Audition“. Mitsuo Yanagimachi does not go that far in terms of extremity, but the shocking element is not toned down at all, while, furthermore, the presentation of the rest of the film is equally exquisite, although in completely different terms. “Fire Festival” is the most acclaimed film of Mitsuo Yanagimachi, being the first of his works to be released in the US, having screened in Cannes and netting a Silver Leopard in Locarno.

The story is based on a real-life case and takes place in the town of Nigishima, a seaside setting that also includes thick forests, situated in the Kumano area, which is considered the cradle of Shinto in the country. Expectedly, the economy of the area is completely depended on logging and fishing, with the inhabitants in essence being separated by their line of work, although a third “caste” includes those who were not born in the area. The balance is almost absolute, but the plans for the development of a new marine park threaten it significantly, despite the fact that the majority of the villagers are for the construction, seeing it as an opportunity for financial growth. Elderly land broker Yamakawa in particular, is the main advocate of the new deal, pressuring every side in any way he can.

On the opposite side is Tatsuo, the protagonist of the film, a boorish lumberjack who is a family man, a womanizer, a mentor, a bully and a weird kind of fanatic who thinks he has a direct line of communication with the Goddess of the forests. His denial to sign away his house to the developers becomes the source of intense friction, particularly after a series of oil licks harm the local fish breeding and the fishermen start believing he is the culprit. His affair with Mariko, who is desired by both Yamakawa and Tatsuo's protégé Ryota, add another level of disliking for him from the villagers, and Tatsuo eventually erupts, during the titular fire festival.

Mitsuo Yanagimachi directs a film that unfolds into two main, interconnecting axes: the contextual one, which presents the life in the area in all its “glory” and the impact capitalistic progress has on tradition, and the environmental one, which has its source in the production values, and particularly the cinematography. Documentary-like realism is an element that describes both axes, but the first one also includes elements of fiction that add to the entertainment the movie offers.

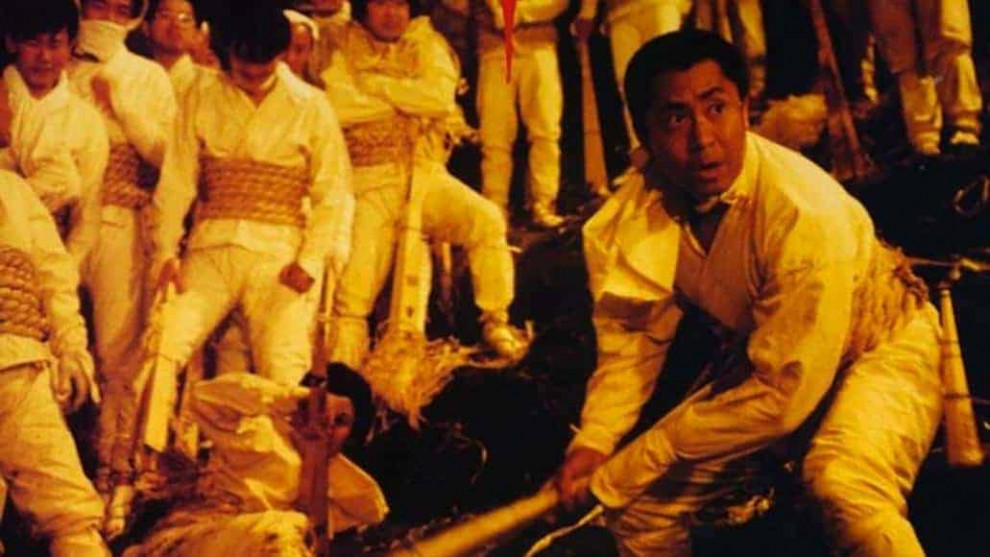

In that regard, Yanagimachi presents the characteristics of the people that live in small, rural places quite eloquently. The sense of community is quite intense, but so is superstition (even if it derives from the deep roots of Shinto religion), the combination of gossip and secrecy, boorish humor, fear of anything that does not follow the “rules” of everyday life, particularly regarding new people (aka strangers), and the subsequent “institutionalization” that derives but also leads to all the above. Tatsuo is the embodiment of all these aspects, a trait that is particularly exhibited in the finale, when the voice of nature and his frustration for seeing his way of life about to be extinct, leads him to eruption. This part has a deep psychological background, as Tatsuo seems unable to handle the fact that he is turned from an alpha-dog and a leader (boss would also be accurate) of the community to a pariah, with his actions during the festival (in the most impressive scene in the film) symbolizing his permanent detachment from the local society that lead to his demise. Kinya Kitaoji portrays all the above characteristics excellently, in a style the frequently reminds of Toshiro Mifune, although Tatsuo is by no means as likable as the characters Mifune portrayed, with this aspect also being presented through Kitaoji's acting.

The second axis, however, is where the film truly thrives. The presentation of every corner of the area, including the forests, the sea, the houses and the bars is depicted through an exquisite combination of artistry and realism, with Masaki Tamura's camera presenting images of extreme beauty even from the smallest detail. The movement of the waves, the trees and the waving of their leaves, the rain, the way the dogs move, the cutting down of the forest are presented gloriously, while the combination with Toru Takemitsu's subtle music induces the film with a ritualistic essence that connects its aesthetics with its context in an ingenious manner. At the same time, a sense of sensualism also permeates the film, particularly deriving from Kiwako Taichi, who portrays Kimiko and her femme-fatale-nature in a style that highlights how different she is from the rest of the villagers.

Some elements of the film are equally memorable and difficult to understand where they come from, with the scene where the boar fights the dogs falling under the first category and the one with the bikers dancing under the second. Perhaps one could say that Yanagimachi wanted to show how out of place modernity appears in such a setting, but this is not fully clear, with this lack of definite answers extending to the whole context of the film, particularly the reasons behind Tetsuo's final actions.

This lack of answers, when combined with the rather slow pace Sachiko Yamaji's editing implemented, which extends the film to more than two hours, could lead to some frustration for the viewer, although the ending definitely compensates to a point. However, the way Yanagimachi and Tamura have shot the film prevents this almost completely, since the beauty of the images is inescapable and actually carry the film almost for the full of its 126 minutes.