Masayuki Suo is a director not afraid to touch on cultural taboos in his work, most notably with 1996's breakthrough “Shall We Dance?”. There, he tackled a foreign influence in ballroom dancing, and its lack of acceptance as a respectable activity for a middle-aged salaryman. His earlier “Sumo Do, Sumo Don't”, however, looks at a more traditional Japanese activity, but how a younger generation embrace the foreign and see the past as taboo.

“Youth” is screening at Japan Society

Shuhei (Masahiro Motoki) is a slacker student, confident that he has no need to go to class or make any efforts, as his family connections have already landed him a job on graduation. There's just one problem with this: he actually has to graduate. As such, he feels it's about time he met with his professor, Anayama (Akira Emoto).

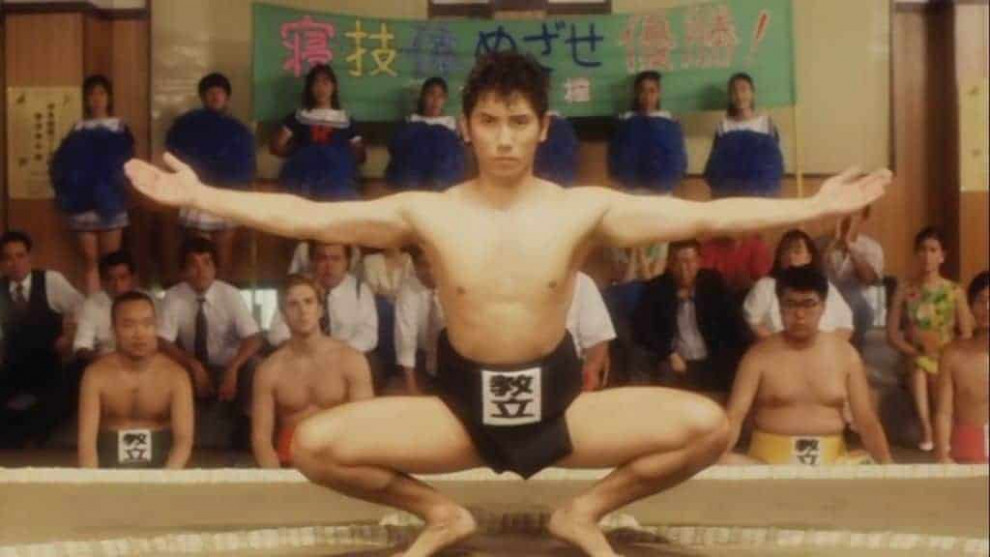

Anayama is something of a sumo wrestling buff; a lean man, but with good technique. He cuts Shuhei a deal: join the university sumo wrestling team and he'll pass him. Seeing this as his only option (above actually studying) – and perhaps aided by his attraction to Anayama's young assistant Natsuko (Misa Shimizu) – he agrees. But he finds a team of a sole member: the keen, but weasely Aoki (Naoto Takenaka). To compete, they will need a minimum of five competitors or face disbanding; already a third division team and an embarrassment to its alumni.

They set out to recruit the remaining trio, forcing the large, but meek Tanaka (Hiromasu Taguchi); the rugby-playing Brit George Smiley (played by American Robert Hoffman); and Shuhei's skinny younger brother, Haruo (Masaaki Takarai), equally attracted to Natsuko's charms. It's enough to compete, but they are far from competitive, beaten by a team of stick-thin no-hopers in their first bout. With the wrath of former team members facing him, Anayama takes the team on one of his infamous summer retreats, where some old tricks see the team develop. It's now time for them to enter the competition, with – thanks to Natsuko's mass media manipulation skills – all eyes on them. Can they finally win a single fight? Of course, it's a sports comedy.

As the Japanese bubble economy came towards its end, sumo wrestling was a sport wrought with match-fixing scandals, seeing the its popularity among the population declining. As with “Shall We Dance?”, foreign influence is on show, with American football and pro wrestling being bigger draws for university students, feeling almost like a US campus comedy. Here, tradition has to fight against these external influences. Being a Christian university, non-Japanese sports get scholarships and cheerleaders, while the sumo team have to do whatever it takes to simply exist. Smiley is deeply opposed to the idea of showing off his naked rear end in public, and as such refuses to join the team – his debt-ridden self is only convinced to join on learning that he can live in the sumo team dorm for free. But he is also unconvinced by the traditional and simple nature of sumo, and so struggles more with the sport itself than any opponent.

The sumo team, therefore, are not just fighting against other, stronger teams – as well as teams of weaklings who can still force them outside the dohyo – but for the Japan that has become lost. Aoki is the only team member who has any sort of knowledge of the sport, if lacking any talent for it. Constantly, he has to remind the rest that it is not a “jock strap” but a mawashi. The team's elders cut a picture of frustration not just at a team incapable of winning, but a group of youngsters who show no respect for their art. Anayama doesn't believe any of them have any passion for sumo; he simply wants to keep the team alive. As such, he makes no attempt to train them to become better wrestlers. He is happier with a poor team than no team at all.

Suo, however, is also critical of sumo's traditions. He is quite happy to include the sacrilege of females entering the ring, with female groupie Masako (Ritsuko Umemoto) even stepping up as a fighter in ingenious disguise. If the younger generation reject sumo, perhaps it's time that it spoke their language a little more.

“Sumo Do, Sumo Don't”, despite its cultural aspects, is very much a sports comedy. We are treated to musical montages of training as we see development in the team's skills; a standard cliché. As ever with this, we see a team of absolute no-hopers become a team of (not quite) world beaters within the space of a hour. The development here, however, perhaps feels even quicker than usual. Their rounds at the competition follow the exact same course throughout, with Suo not exactly making it seem a sport of exciting variety for any non-converts.

There are also a lot of mainstream comedy staples littered throughout, with much made of the amount of the backside on display for sumo wrestlers; and indeed there is a lot of bum on show. Aoki suffers from near crippling diarrhoea whenever he steps in the ring, resulting in the sort of exaggerated dance Takenaka would later reprise in “Shall We Dance?”.

Indeed, much of the cast would later feature in Suo's most famous film, but here they look more than just four years younger. Motoki is the undoubted hero with crowd-pleasing good looks, though switches between cool and bemused as he seems to in every role he has played. Takenaka also stands-out as Aoki, with his irritating, but charming, overzealous comic acting.

For “Sumo Do, Sumo Don't”, Suo is wrestling with the stereotypical image of sumo, and indeed how many foreigners can blandly equate Japanese culture to simple novelty. He portrays sumo as somewhat more accessible than you might think – most of the fighters on show are normal in size, or indeed skinny weaklings. This is not just a sport of the oversized, or indeed male. We can all get off (and show) our backsides underneath our jock straps. Sorry, mawashi.