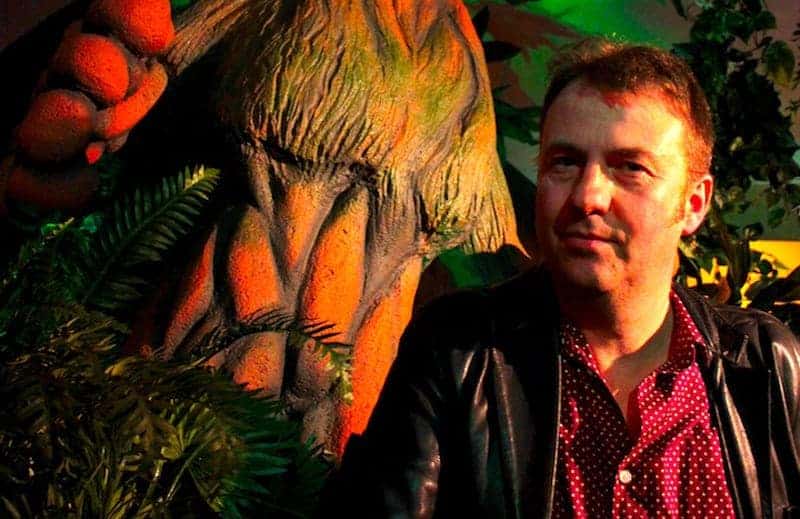

Jasper Sharp is a writer, curator and filmmaker specialising in Japanese cinema, and co-founder of the Japanese film website Midnighteye.com. His book publications include The Midnight Eye Guide to New Japanese Film (2003), joint-written with Tom Mes, Behind the Pink Curtain (2008) and The Historical Dictionary of Japanese Film (2011). He is the co-director of The Creeping Garden (2014), alongside Tim Grabham, a documentary about plasmodial slime moulds. He has programmed a number of high profile seasons and retrospectives with organisations including the British Film Institute, Deutches Filmmuseum, Austin Fantastic Fest, the Cinematheque Quebecois and Thessaloniki International Film Festival.

We spoke with Jasper no longer after his talk – in recent, more social times – on Ero Guro for the Miskatonic Institute of Horror Studies in London, and we discussed about how he got sucked into the wild side of Japanese Cinema, the years of Midnight Eye, his latest passions and more.

Hi Jasper. In the intro of your book “Behind the Pink Curtain” you say that once upon a time, you were in a London cinema watching Koji Wakamatsu's “Violated Angels”. Can you tell me what that film moved in you and what kind of chain reaction and events it triggered?

It's funny thinking back about that moment because I'm revisiting it now for work purposes from another perspective. I used to be a big horror fan as a teenager and made it my duty to work my way through all the entries in a book called “The Aurum Film Encyclopedia of Horror”. The first edition had what I then thought was every horror film ever made up to about 1984, although I now know there were quite a few gaps, especially for non-Western films. Of course I was watching a lot of these films on TV or on VHS, including getting hold of them on the tape-trading network, but even then, hardly any Japanese films were released on VHS during the 1980s in a version I could watch (i.e. subtitled in English). So my viewing was mainly American and European films. The book included “Violated Angels“, rather strangely, I think, because I don't really think of this as a horror film.

When I moved to London in 1989, I used to frequent the Scala Cinema in Kings Cross, and I noticed one day that this film was screening there, and as I was familiar with the title through the Aurum Encyclopedia, I thought I'd tick it off the list. It was playing on a double bill with Shohei Imamura's “Ballad of Narayama“, and I can honestly say I'd not seen anything like either of the two films before. I think I had seen “In the Realm of the Senses“ by this point on a bootleg video, and even some Shuji Terayama films late night on Channel 4 back in the days they played this kind of stuff, and also a few other things like “Onibaba“and Kinji Fukusaku's “Samurai Reincarnation“, but this was really as far as my experience of Japanese cinema really went.

The ironic thing, given I was later to write so much about Wakamatsu and meet him a few times, is that I was more moved by Imamura's film. I found Wakamatsu's film completely alien and odd, and couldn't, as an 18-year-old growing up in a different generation in a different cultural context, work out what the hell it was trying to say. I wasn't really sure at this time what Imamura's film was trying to do either, but it really intrigued me and on an emotional level I found it much more engaging. It would be some years before I really got interested in Japanese film, which was around the time that Imamura's “The Eel“ won the Palme d'Or and got a UK release in 1997/98, so I already had some acquaintance with this director then.

Then when I was living in Amsterdam for a bit, around 2000, there was a big retrospective of Japanese cinema at the Dutch Film Museum and they screened another Wakamatsu film, “Secret Acts Behind Walls”. I don't think I was in any way more enamoured with this than I was with “Violated Angels”, but you know, both films stuck with me as something different, something quite unsettling. It was only a few years later when I was living in Tokyo and started meeting pink film directors and learning about the whole scene that I began to appreciate these films within a particular context and where these sat within wider Japanese film history. But no one had really written much about Wakamatsu and where he sat within the wider scheme of things at this particular point.

In which way Wakamatsu production and some of the pink film industry eventually converged with the left wing and student movements?

It's a tricky question to answer inasmuch as that in the 1960s, I don't think you could say there was a homogenous thing called the pink film industry, just lots of small independent outfits making films with more explicit and scandalous content and selling them cheap to cinemas who were trying to make up the shortfall because the major studios had stopped producing so many films at this point. One thing these pink producers and directors did share however, was that they were all outsiders to the major studios, so this encouraged a sort of oppositional stance, pretty much like punk did with the music industry in the late 1970s. Independent filmmakers were freer to say things politically and to critique the system in the 1960s than the previous generation, so they took this opportunity enthusiastically.

At the same time, you had the whole postwar generation growing up, who were anti the whole idea of Imperial Japan and the old nationalist ideology that had led the country into the war, and were also strongly against the idea of American imperialism and Japan siding with America in its Cold War campaigns in Asia. So, a strongly politicised youth and student movement emerged and certain filmmakers either allied themselves with this anti-authoritarian stance or just realised there was money to be made catering for it. Students tend to be as interested in political idealism as they are in sex, so it was a natural marriage in many respects.

In your Ero Guro talk, you concluded that the genre is still alive and kicking. What about Pinku Eiga?

What I was trying to say was that if we are talking about Ero Guro less as a genre and less as a cultural phenomenon rooted in a particular place and time, and more in terms of a particular mindset or an attitude, then yes, the basic juxtaposition between horror and sex in a gaudy, absurdist and carnivalesque manner is indeed still thriving in various media forms produced in Japan.

Pink film, as I describe in Behind the Pink Curtain, was traditionally defined as independent feature-length narrative films sold on their erotic content that are shot and distributed on 35mm film to a specialist network of adult-only cinemas. And they are generally pretty soft compared with hardcore pornography, so there is a big distinction to be made there too. The industry was still functioning in this form when I was living in Japan in the early 2000s until the time my book was published in 2008, although you could see the writing was on the wall. The real killer came with digital projection, because it was cheaper for filmmakers to shoot on digital, but the traditional pink cinemas still had old film projectors and not many cinema owners were going to spend the money to upgrade to digital projection to keep a dying industry afloat. So around 2012, you could see a lot of independent cinemas in general closing down and their buildings sold off to developers, including pink cinemas. Some did convert to digital projection, but not many, so basically there were few outlets for pink films. You can still watch erotic content by other means, like online or on DVD or whatever, but the basic features I mentioned that defined pink cinema all disappeared.

I don't know about the current state of the industry as I've not kept up with it really, but the directors who all made their name in this field have mostly moved on to other things and it certainly isn't an arena now where you could make your name and go on to make more mainstream films. You could of course argue that pink film as an attitude and a state of mind still exists, just like Ero Guro, but by the definition of erotic films made exclusively for screening in cinemas, the pink film industry is a pale shadow of what it was from the 1960s up to the 2000s, although I do believe it is still hanging in there.

Can you tell us a bit about your Midnight Eye adventure with Tom Mes? How it all started and its legacy.

I'd always been interested in cinema, but my teenage interest in horror moved towards arthouse and more experimental films as I did a lot of travelling and living abroad in the 1990s, mainly European cinema. I became more interested and adventurous in exploring different cultures through its cinemas, and this is when I first started becoming interested properly in Japanese cinema – the ICA were showing things like the Kitano films, Sogo Ishii, “Perfect Blue“, “Like Grains of Sand“ etc in the late 90s. There really wasn't a lot of Japanese films to watch in the UK at this time though, so my interest wasn't really obsessive. I moved to the Netherlands in 1999 with a job working as a computer programmer for Yellow Pages, and the video shops were amazing, so I suddenly had lots of access to films I couldn't see before, and this is when the Japanese bug really bit.

I soon realised I would go out of my mind if I continued working in IT, so I thought about moving to Japan to teach English and started watching loads of Japanese films to prepare myself. There was also a big focus on Japanese cinema at Rotterdam Film Festival and at the Dutch Film Museum around this time, and it was the early days of the internet, and DVDs were then a really new thing, so I could order films online from Hong Kong or other countries that used English or French subtitles, and I got back into tape trading again, and soon had access to this whole new world of cinema that I barely realised existed in such a scale, and very little had been or was being written about it.

And it was at this time I met Tom, who was running a different cult film website at the time, and he felt a similar way about Japanese cinema as I did. I always had this idea of becoming a writer, but could never think of anything to write about, so now I had a subject, through the internet I had an outlet, and with Tom I had a likeminded spirit and source of mutual encouragement, so it was a perfect combination. And about a year or so later, I did move to Japan and found myself with much closer access to the films and also to a good many filmmakers, who were all really approachable.

I was amazed by the immediate impact of the site. We featured a lot of interviews with directors whose work wasn't being released outside of Japan at the time – Naomi Kawase, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Takashi Miike etc. We basically were in the right place at the right time to ride the new wave of interest before it broke, because of titles like “Audition“, “The Ring“, “Battle Royale“ etc, but we also were keen to explore more historical stuff like silent cinema, documentaries, micro-budget indie films and arthouse too – anything that was Japanese moving image culture.

We were the first English-language website to focus purely on Japanese cinema and I would also make the bold claim that I was one of the first critics who actively moved to another country specifically for the purposes of researching and writing about its cinema for the internet and without any outside funding or academic support. I don't know about the legacy of Midnight Eye, but in terms of immediate impact, we were regularly getting requests from festivals and distributors either for contact details for the films we discovered or advice on what was worth looking at from Japan, so I know there's at least a few films out there that might never have got shown overseas if it weren't for Midnight Eye.

The other thing which I think is pretty cool, is that there are a load of other sites now, like Asian Movie Pulse, Eastern Kicks, Windows on Worlds etc, and a whole wave of new writers out there who are carrying on covering Asian cinema. There's no shortage of information out there at the moment and while it was common to see the attitude when we started Midnight Eye that either Japanese cinema was dead, or that there was no reason why non-Asians should be interested in Asian cinema, people don't think like this anymore. I think the whole success of Studio Ghibli or more recently the “Parasite” phenomenon really goes to show how globalised film culture has become and how established canons of the world's great directors has now shifted. I'd like to think we were a part of this movement.

What is the guiding theory and also the practice behind your film criticism? Has your method changed since you reviewed your first film? And are there any movies that you have drastically changed your opinion on?

I think I had two main approaches when I was writing for Midnight Eye. The first was that we were writing about films with no commercial currency, meaning that they weren't necessarily being released in our own countries so we didn't need to “sell” them as such and curry favour with film publicists or distributors. So we were relatively uncontaminated by the financial side of the industry, but also because as a downside we weren't getting paid for writing the reviews either. This meant that we could choose what we wanted to focus on. If there was something we liked or found interesting, we could draw attention to it when no one else really was, and if something was shit, rather than spend ages tearing it apart, which is something I've never really been that keen on, we could just save our time and ignore it.

The second was the other liberty of writing for the web on a subject no one else was really writing about at the time was you weren't limited by word counts like you are in print. I've never been a big fan of the “say what you see” school of film criticism, so maybe I think with Midnight Eye, it was more a case of using a particular film as a starting point to explore other aspects of the Japanese industry or culture or just my own ideas. I'd like to think we operated in this space that allowed for intelligent, discursive writing for a general audience that wasn't too theoretical and academic, and I'm not sure that space really exists any more. I do have a PhD in film studies myself, but my main issue with academic film scholarship is that it's so closed off from everyone else, it just feels like a small coterie of university lecturers or professors just talking among themselves using impenetrable jargon, and anyway, no one without access to a university library can access their research or read the books that the academic publishing industry makes far too expensive for non-academics to buy. My hope with Midnight Eye was that we could be informative, thought-provoking, enthusiastic, insightful and ultimately accessible, so as to encourage an interest in our passions.

As for the actual idea of film criticism, I guess I usually ask myself the basic questions of what is the filmmaker trying to achieve, why are they trying to achieve it, do they achieve it, and if not, do they achieve something else interesting by accident? And as I'm now more involved with writing things like liner notes or articles about older titles, as opposed to reviewing new films, I'm really more interested in the historical or cultural context in which the films are made. I don't know if there are titles or filmmakers I've radically changed my mind on, but I would say in relationship to all this, that when I first started out with Japanese film I might have found Kiyoshi Kurosawa slightly lacking when it came to delivering the standard shocks one might expect from a horror film, but quickly came to realise that what he was doing so differently was far more interesting, while at the same time, perhaps some of the new wave films of the 1960s are rather less interesting the more you see them and the more you know about them.

You told me you are not very into modern Japanese cinema. In your opinion, what is it that is missing in modern Japanese cinema and what is your general view of the industry?

I think it's natural enough that I'm not as enthusiastic about contemporary Japanese cinema as I once was, and that my enthusiasm would have dampened somewhat after the initial excitement of discovering this whole new world. I think it's probably a similar symptom to what Donald Richie must have felt, going from writing about Ozu or Kurosawa right in the midst of its 1950s Golden Age then being stuck in the 1970s heyday of Roman Porno and Toei yakuza movies and throwing up his hands in disgust, or Tony Rayns bringing Sogo Ishii and Kitano films to the UK in the 1990s and then getting rather jaded with the J-horror boom and its aftermath. The question is whether it is me in particular that has changed, or the industry. I think my relationship to cinema in general has changed in this new age of instant access and digital projection – the magic of going to the cinema I felt when I was younger isn't really there anymore, and there's no real sense of discovery because everyone else seems to have seen everything already beforehand and already stuck up their thoughts on Facebook before I get a chance to see a film for myself, so finding those unexplored nooks and crannies or making new discoveries is a lot trickier.

That said, there was a stage when you look back in the final years of Midnight Eye that all of the writers were really beginning to struggle when it came to come up with our annual best-ten lists. As with a lot of countries in the world, the big releases were being crowded out with glossy but conservative TV tie-ins or other franchise material, the mid-range had disappeared, and the real low-budget indie section was being crowded out because there was no place to show their films. There just seems to be a general lack of edge or purpose or fight to Japanese films now, I think. A lot just seem to be being made to fill screens with. There may be films out there being released now that might inspire the same level enthusiasm as stuff like “Tokyo Trash Baby“, “The New God“, or “The Glamourous Life of Sachiko Hanai“ did when Midnight Eye was in its heyday, but I don't feel any real drive to go and look for them, especially as there seem to be so many other people out the moment who are more enthusiastic, and especially as I find a lot more excitement in going back looking for old classics I haven't discovered yet. I still think there's at least a third of Seijun Suzuki's output I haven't seen, for example.

Can you name a contemporary Japanese director you like? Or a promising one?

I think Hirokazu Koreeda is the only consistently brilliant director in Japan who can be discussed in international terms, rather than just within the context of Japanese cinema. Kiyoshi Kurosawa is always interesting, even if not always so consistent. I don't keep my ear to the ground as I once did, so no, but I was always very interested in what was going on in the field of independent animation, so Mirai Mizue's short abstract films I always found really delightful. But you know, I've always argued that there are so many Japanese films coming out every year that by the law of averages you are always going to stumble across a few mini masterpieces if you look hard enough. I'm just looking elsewhere now, because I don't really programme for festivals anymore as I did for about a decade from 2006-2016.

I would like to ask your opinion about two recent productions that, in a way, deal with your area of expertise. One is the TV miniseries “The Naked Director” and the other is Kazuya Shiraishi's indirect homage to Wakamatsu “Dare to Stop Us”.

I'll be honest, I've not seen ‘The Naked Director” – I'm not massively interested in the subject of Japanese sex films per se. My interest in pink films was more to with how it fit into the wider Japanese film industry and the historical context in which directors like Wakamatsu operated. With regards to “Dare to Stop Us”, I was quite disappointed, because while it dramatises this behind-the-scenes background to Wakamatsu's pink film career, it really didn't provide any insight or any motivations to him as a character. It seemed like by-numbers filmmaking. I didn't get any sense of engagement with the politics or the culture of the time, which is a shame as it really is such a fascinating era.

Can you tell us something about your “slimy” passion, how it started and how it became a book and a film?

You are talking of course about “The Creeping Garden”. I guess the main upshots for me of become a film critic is that I've turned what was once a hobby and a passion into my main source of income. Watching films doesn't really feel like downtime when you spend most of your life stuck indoors looking at a screen, so I do love getting outside and about in nature, and because of this I became really interested in mycology – searching for and studying mushrooms and toadstools and other fungi. And this sort of has its similarities with Japanese cinema for me, in that there aren't really that many people out there who know about the subject, just a few obsessive specialists and fanatics, but once you start looking you realise there is a hell of a lot to discover. I can be outside for hours throughout the year looking for fungi to get the perfect photograph of and to try and identify it and work out why I found it where it was, what other plants or trees or ecosystems it associates with, if it is rare or not or suchlike. It's a good motivation to get some exercise and appreciate the natural world and it's basically all a free source of entertainment.

This is what led me to learn about slime moulds, which are something very different from fungi, because they move and seemingly with their own sense of direction that some attribute to them having a rudimentary intelligence – they can crawl through mazes to find food for example. Years and years ago now I was chatting to Tim Grabham, an animator, filmmaker and all-round visual artist who had just co-directed a film called “KanZeOn” (2011) about the ritual use of sound in Japanese religion, which I was then just about to screen at the film festival I was running in London, Zipangu Fest. I started talking to him about slime moulds and said they'd make a good topic for a film and he jumped at the bait. As an animator, he was fascinated with filming these blob-like materials using time-lapse to explore their movements and textures, so we ended up making the documentary “The Creeping Garden” together. It took several years, but it ended getting a good festival run after its premiere at Montreal's Fantasia in 2014 and a theatrical release in North America and then a Bluray release.

From the perspective of a writer, I am fascinated by how the language one uses is so heavily influenced by the subject you're writing about, but also how the documentary film format both limits what you can say in terms of delivering factual content but also gives a very different sense of expression, especially when you are trying to communicate science. And so I wrote the book of “The Creeping Garden”both as a way of mopping up the overflow from our research from the film, but also looking at the means and methods we used to make it. I really enjoyed writing it as a side step away from writing about film, although I guess in one sense I was writing about film. That said, I've continued to find a lot more slime moulds in the wild since “The Creeping Garden”project, and it makes me realise that there is still so much more to say about this absolutely fascinating organism, so it's a subject I might well find myself returning to in the future in some capacity.

Are you onto something at the moment?

I'm doing a lot of work on forthcoming home video releases as well as other writing mostly tied in with the cultural exchanges around the 2020 Olympics that ironically aren't even going to happen now in these bizarre times. I've got a whole load of other projects I really want to apply my time and energies too once the current state of affairs related to this damn virus has settled back to something approaching normality. I've mounds of research on the first Chinese-American Hollywood star Anna May Wong's various stays in London that I am going to turn into a book, and at least one documentary about the magic of fungi and its interactions with the environment that I've already started filming. I always hate talking about these kind of work-in-projects project in case I jinx them and they never happen, but I've done so much work on these both already that I know they are both going to happen in some form or other!