By Abdul Rahman Shah

“What's even a Malaysian cinema?” was the question my mind ponders, as I think of a way to introduce this overview without boring the readers on the aftereffect of colonial decision-making that influenced and still influencing how we, Malaysians, perceive ourselves as Malaysians. Where the answer to it would differ greatly between and within historians, academics, cultural professors, politicians, artists and so on depending on how they would define what is uniquely, culturally Malaysian when we are so diverse. There is no one definition that everyone would agree to outside of the boring legislative perspective of having an identification card and/or passport identifying you as a Malaysian.

So, how do we define Malaysian cinema when it is hard to even define what is being Malaysian? Although there are attempts at defining “national cinema” in Malaysia such as the FINAS Act 1981 (FINAS is the acronym for National Film Development Corporation Malaysia, a government agency) which defines it through the usage of language (the Malay language to be precise). This policy in principle would sideline movies made by Malaysians in a different language. There was also something called the National Cultural Policy debated in 1971 that influenced the 1981 act, but it never was an actual policy but often times quoted as if it were.

Is language the only criteria for a film to be called Malaysian? Would a hypothetical film made by Russians, about the life of Russians, with Russian culture all over – but the dialogues are in the Malay language, will that movie become Malaysian?

Although this demarcation line kind of only exists within the local mainstream market as even FINAS have a list in their website of Malaysian films that won international accolades that includes independent and non-Malay films that never really benefitted from their policies. In other words, the mainstream Malaysian cinema is often seen as Malay cinema, but this perspective is slowly changing.

There was a controversy in 2016, when two highly rated non-Malay Malaysian movies, Jagat (2015, dir. Shanjey Kumar Perumal) and Ola Bola (2016, dir. Chiu Keng Guan) could not even be nominated as Best Film in the Malaysian Film Festival due to the language policy – which before there existed a secondary award named Best Non-Malay Film which is usually slated for these movies. After backlash from film practitioners, FINAS changed the categories – but not really. For the 2016 awards, Best Film includes all Malaysian movies regardless of language, but they decided to create another unnecessary category in Best Film in National Language, which made a different set of film practitioners to riot. Eventually, in 2017, both categories were merged to become one, just one Best Film category. So problem solved?

Is there a different way then to define Malaysian cinema without going into the persisting racial, political, colonial issues? Something as simple as, it is a Malaysian film if it was made by Malaysians for Malaysians about Malaysia, etc. etc. – but even this simple seemingly all-encompassing definition falters when looking at a recent English-language film, The Garden of Evening Mists (2019, dir. Tom Shu-Yu Lin). Defined as a Malaysian film, made in Malaysia, adapted from a Malaysian author's English novel (just to point out literature in Malaysia have the same “national language” problem), produced by a Malaysian company, even supported by FINAS – when it was directed by a Taiwanese, screen-adapted by a Scottish person, and acted by talents from various nations even nominated and won in the Taiwanese Golden Horse Awards last year, which awards was established to celebrate Chinese cinema all over the world. So, is the film part of Malaysian cinema or Chinese cinema? (Plot twist: it can be both, and more).

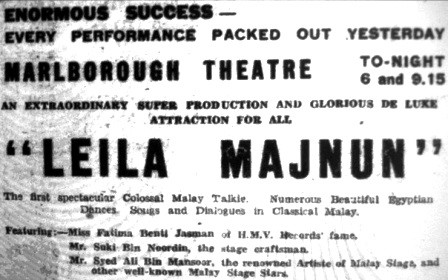

Which point I wanted to make is the difficulty of defining a national cinema much more the ridiculousness of adopting an essentialist view towards this issue in an ethnically complicated post-colonial world, especially with globalization right at our doorsteps – although at times we might have to do it in specific situations, including the writing of this essay. I could actually make the same point with an older film, often touted as the first Malaysian (Malay) film, Leila Majnun (1933) – which was made during the colonial times in Singapore (then part of British Malaya), produced by an India-linked production company (Motilal Chemical), directed by an Indian (B.S. Rajhans), with multi-ethnic crew members, adapting a Persian romantic folktale for a Malay audience. So, is it a Malaysian film or a Singaporean film or an Indian film or a Persian film?

But I digress.

The Golden Age of Malaysian Cinema

The Golden Age era was spurred during post-independence with two production houses, the Shaw Brother's Malay Film Productions and Cathay-Keris Studios , between them a total of 250 films between the two decades. According to Malaysian cinema scholar Hassan A. Muthalib – the films made during this time were largely influenced by the directors at helm, which the majority were Indian directors who brought Indian cinema stories which influence bleeds into latter movies even when directed by Malay directors. Reductively, we can say the industry at that time were produced and distributed by the Chinese, directed by Indians, and almost wholly acted by the Malays.

Slowly, there was a shift towards films being directed by the Malays themselves in creating a film more unique to the Malay experience, culture and zeitgeist which gave us the now iconified, internationally celebrated, multi-talented Malaysian filmmaker, actor, singer, and etc. – the late P. Ramlee. He and in general his peers made movies that reflects the current Malay psyche, the need to balance between rapid modernization and tradition. His films mainly uses satire and comedy to explore the meaning of, “What is it to be a modern Malay person?” while also dabbling into social class critique. But the movies at that time, as film scholar Hassan A. Muthalib put, lacked criticism towards the colonial powers in comparison to literature and journalism.

“In my opinion, Malay cinema then can only be regarded as an artificial cinema – being only a construct of the studios that produced the films that were only meant as entertainment for the masses. Unlike Indonesian, Filipino and Thai cinema, there is no film then or till this day, that is critical of the British and their presence in the country as colonialists.” (Hassan A. Muthalib, 2017, 120 Years of Malaysian Cinema: From Shadow Play to the Silver Screen).

Several notable films made during this Golden Age era are:

- Penarek Becha (Malay Film Productions, 1955, dir. P. Ramlee)

- Semerah Padi (Malay Film Productions, 1956, dir. P. Ramlee)

- Pontianak (Cathay-Keris Studios, 1957, dir. B.N. Rao)

- Pendekar Bujang Lapok (Malay Film Productions, 1959, dir. P. Ramlee)

- Nujum Pak Belalang (Malay Film Productions, 1959, dir. P. Ramlee)

- Hang Jebat (Cathay-Keris Studios, 1961, dir. Hussein Haniff)

- Abu Nawas (Merdeka Film Productions, 1961, dir. A.R. Tompel)

- Ibu Mertuaku (Malay Film Productions, 1962, dir. P. Ramlee)

- Chuchu Datok Merah (Cathay-Keris Studios, 1963, dir. M. Amin)

- Mat Bond (Cathay-Keris Studios, 1967, dir. Mat Sentol)

The Maturation Period

The 80s to 90s sees a different type of Malaysian cinema to be made. If the zeitgeist in the 50s and 60s is about negotiating modernity, the 80s and 90s somewhat is the result of that negotiation – a more urbanized and critical Malay community. This period also, in the political sphere was when Islamization took root to the point rock stars were forced to cut their hairs and let go of their heavy metal and glam rock aesthetics to be on TV. There are films on the dark urban underbelly such as Kembara Seniman Jalanan (1986, dir. Nasir Jani), Seman (1987, Mansor Puteh), and films depicting sexual explorations such in Rozana Cinta 87 (1987, dir. Nasir Jani) and Perempuan, Isteri, & Jalang(1993, dir. U-Wei Hajisaari). Funnily enough just a few days back a clip from Langit Tidak Selalu Cerah (1981, S. Sudarmaji) went viral on Malaysian Twitter because of how heavy handed it metaphorically depicts sex, with a video of a construction drill spliced between the scene.

The Little Cinema: A better representation of Malaysian Cinema?

“A 'Malaysian cinema' began with Amir Muhammad's feature film, “Lips to Lips” in the year 2000. A flurry of films soon began to be made not only in the national language (Malay) but also in the various ethnic languages like Chinese and Tamil that were liberally interspersed with English. It was something that had never happened before. International film festivals and scholars began to take note of these alternative films by young filmmakers who were articulate with stories from their own communities. A truer reflection of a multi-ethnic, multi-religious and multi-cultural Malaysia burst onto the screen. This movement became known as The Little Cinema of Malaysia. Some of the filmmakers matured and went into the mainstream but still maintained their alternative approaches.” (Hassan A. Muthalib, 2017, 120 Years of Malaysian Cinema: From Shadow Play to the Silver Screen).

The above quote shows there is a shift in wanting to represent all of Malaysia and not just about the struggles of one community. Although The Little Cinema more or less exist only in the independent scene that slowly gained national recognition with more interesting, relatable stories even when it is not in the Malay-language. Plus, in my opinion, also due to the narrative downfall of popular mainstream Malay cinema post-2000s until today, even if they're successful monetary wise.

This period also saw the emergence of another beloved, celebrated director, the late Yasmin Ahmad. She, like Amir Muhammad, cinematically presented a more multi-cultural side of Malaysia with all of her features – Sepet (2004), Gubra (2005), Mukhsin (2007), Muallaf (2008) and Talentime (2009) – are positively reviewed by the media and studied vigorously by film scholars. Other notable directors either part of The Little Cinema movement or not in this post-2000s period are Dain Said, James Lee, Mamat Khalid, Bernard Chauly, Adflin Shauki, Nam Ron, Al Jafree Md Yusop and several more.

Yet, defining Malaysian cinema as needed to be cosmopolitan, multi-cultural with diverse narrative might not be as all-encompassing too. For example, the already mention Jagat (2015) is a gritty representation of the rural Indian community experience in Malaysia made fully in Tamil – is this film less Malaysian by definition? Either by the national language requirement or cosmopolitan imaginations? No one will say that. It escapes definition, or attempts at essentializing a definition but is fundamentally still Malaysian.

Conclusion

The current day Malaysian cinema is a continuous negotiation, a debate of post-colonial national building, multi-cultural idenitity, multi-religious reality and global cosmopolitanism on what is Malaysia itself and how we are presenting and representing ourselves through the cinematic art regardless of genre and approach. In the end it is that simple, Malaysian cinema is Malaysian cinema, do come and watch some.