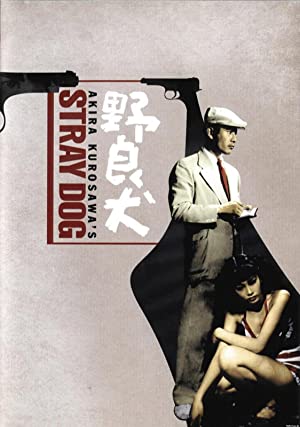

While Akira Kurosawa did not always have the highest opinion of his 1949 effort “Stray Angel”, as he thought it was “too technical”, there is no doubt that his first collaboration with screenwriter Ryuzo Kikushima has its rightful place among the great films made by the director (he would also change his opinion on the film later on in his life). Loosely based on an unpublished novel by Belgian writer Georges Simenon, it can be seen as a precursor for his later detective dramas such as “High and Low”. As with many of his features of that time, “Stray Dog” is also a portrayal of post-war Japan, of the deep wounds left by the war and the structure of its society which is revealed to a police officer after the loss of his gun.

Watch This Title

After some practice on the shooting range with his colleagues, rookie detective Murakami (Toshiro Mifune) is eager to return home. However, during his ride in a crowded trolley, his gun is stolen and even though he is able to chase after the supposed thief, he quickly loses sight of him in the streets of Tokyo. Disgraced and ashamed, he reports the missing gun to his superiors and wanders the streets, the back alleys, the black markets and various other establishments in search for the gun or any traces to the thief. With each day passing by without any leads, he becomes increasingly nervous and uncomfortable, a fear which is confirmed after he hears his gun was used in a murder.

Guilt-ridden, he joins the investigation led by senior detective Sato (Takashi Shimura), who tries to comfort the young detective at his side, trying to convince him they will be successful. As their investigation leads them deeper into the lives of people defined by the repercussions of the war, Murakami's guilt increases as another murder happens.

On the surface, a viewer tends to agree with Murakami's superiors and colleagues for the loss of the gun is unfortunate and will have administrative consequences for the young detective, but especially as the story progresses we have to recognize the scale of guilt and the extent of the repercussions of what has happened. Being a war veteran, the loss of his gun equals a loss of respect, not only in the eyes of the people above him in the structure of the police, but most importantly, in Murakami's own. As he has suffered a series of losses in his life, for example, he has lost his knapsack as a soldier, another loss adds not only to his feeling of guilt, but also his sense of self-inadequacy. Losing his gun becomes an unforgivable loss for Murakami and as a consequence, the task of re-acquiring it, an existential exercise.

Similar to Kurosawa's 1948 yakuza film “Drunken Angel”, Takashi Shimura and Toshiro Mifune can be regarded as two figures of exemplary nature for the facets of post-war Japan. While the older detective has find his own way of coping, the young detective is unable to forget the experience and the trauma with the search for his stolen gun bringing him ever closer to relive these events. Both actors excel as one tries to comfort the other, urges him kindly to concentrate on the task at hand rather than let his emotions take over, whereas Mifune manages to show us a man torn apart by his experiences and an act of carelessness he cannot forgive himself.

As with many of his film noir-inspired movies, Kurosawa shows Tokyo in a very distinct light, emphasizing how recent history has not only shaped its inhabitants but the general structure of the city as well. In what has to be the most artistic sequence in the film, we see a collage of Murakami's experiences and encounters as he wanders the streets in search for his gun. The series of overlapping images of streetcorners, vendors and dodgy establishments highlight the dark maze the detective goes through in search for what seems like a needle in a haystack.

In the end, “Stray Dog” is a remarkable work by Akira Kurosawa about the sense of loss and guilt in post-war Japan. Supported by its image of the city and the brilliant performances by its two male leads, “Stray Dog” manages to secure its position among the director's finest works.