Sonthar Gyal was born in the Tibetan region of Amdo Qinghai. His father was a primary school teacher who was the first person to graduate from college in the region. Sonthar Gyal studied at the Tsolho Nationalities Teacher Training College in Hainan (Tsolho) Prefecture and taught in the nomadic community for three years. Afterwards he received a scholarship to study fine arts at the Qinghai Normal University in Xining. After graduating in 1998 with a B.A. in Fine Arts, he worked in the Tongde Cultural Museum

Encouraged by his friend Pema Tseden, Sonthar Gyal followed him to the prestigious Beijing Film Academy, where he studied cinematography for 2 years with the support of Trace Foundation. Upon graduation, he worked as a cinematographer and artistic director for a series of films and documentaries, many directed by Pema Tseden. He made his directorial debut in 2011 with “The Sun Beaten Path“. His filmography as director includes “River“, “Ala Changso” and “Lhamo and Skalbe”. Recently, he also set up Garuda Media in Qinghai, which functions as both a film studio and his office. Sonthar Gyal is also a teacher in Tibetan, Chinese and art.

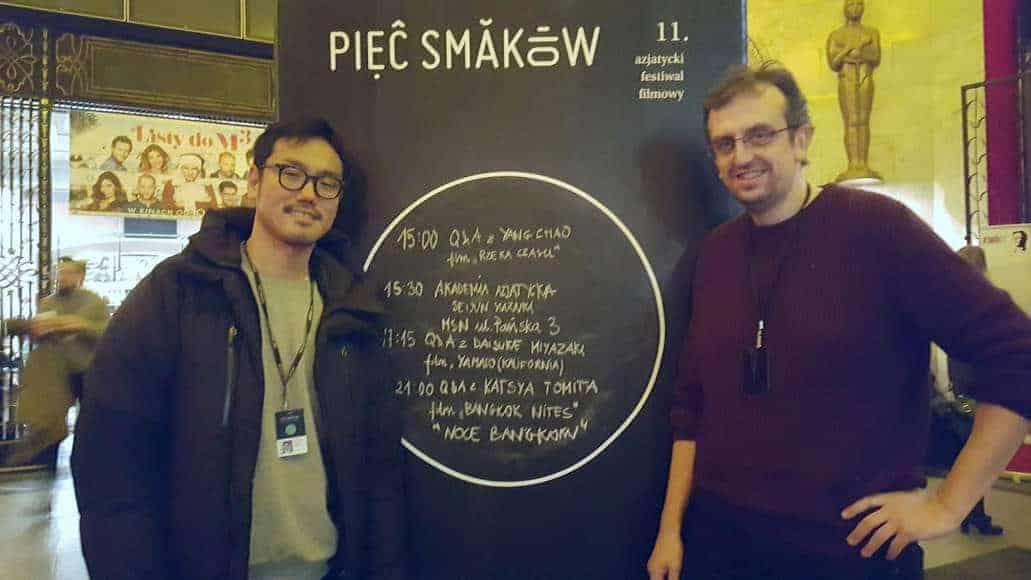

We speak with him about his life and career, shooting in Tibet, the various motifs in his films, and other topics.

I understand there is still no movie industry in Tibet, but can you give us some details about the state of film in Tibet (filmmakers, movies, actors, technicians etc). Is one of your purposes to change that, and create a Tibetan movie industry?

Before, Tibet had no film industry, but they had translation studios. There are almost no films with Tibetans participating in scripts, filming and performances. Some minor movie studios shoot Tibetan-themed films, but they use Mandarin and are shot by a Han team. Pema Tseden's film “The Silent Holy Stones” is the first film shot exclusively by a Tibetan team. I was the art director of the film. Pema Tseden went to the Beijing Film Academy in 2003. I did in 2004. Since then, more and more Tibetans have gone to the Film Academy to study film. According to my understanding, there are many Tibetan students working in different industries, and the situation is getting more and more optimistic.

How difficult is it shooting in Tibet? Can you also mention some of the benefits of shooting there?

Shooting in Tibet is not very difficult. Most of our team members are Tibetans or people who have lived in Tibetan areas, so they can adapt well to the climate. We are all telling stories of Tibetans, so shooting in Tibet is more realistic. This may be the benefit.

Recently, you built a movie studio, Garuda Media. Can you give us some more details about it?

In 2016, Garuda Media was established with the help of the local government. Since my first film, a group of young people have followed me, so Garuda Media is also to train these young people, including scripts, photography, animation and so on. We have sent people to Japan to study animation in particular. They returned to China recently, and may develop the field of animation in the future. Garuda is a mythological creature, which appears in Buddhist texts. I built this base in my hometown. There may be two Tibetan films to be filmed this year there.

You repeatedly cooperated with Pema Tseden. What can you tell us about your collaborations? What do you think are the main differences between him and you as filmmakers and what are the similarities?

We used to work together in the past, Pema Tseden took me to the Film Academy. Before, we wrote novels together, eventually I quit my job and went to Beijing to study film. Pema suggested that I could study photography, which would also benefit future cooperation, so I studied photography for a year at the Film Academy.

I am not sure of the differences between us. I also write scripts and shoot films. Pema is a novelist, and he has a strong grasp of the script. I am a painter, so I think it is better to control the picture, probably this is our main difference.

One of the purposes in your films seems to be to present the reality of Tibet with as much realism as possible, stripped from any cliches and exotification. Can you tell us a bit more about that?

I was born in that land, while other people seem to show as much as possible of Tibet as they had it in their minds, before coming to Tibet. I think this approach is uninteresting, it lacks too much of what the people in the land are really thinking. I dare not say that my films represent real Tibet, because Tibet changes every day, but that my films show, at least, my true feelings.

In “The Sun Beaten Path”, the scene close to the end, when Nima looks at the bus window and sees himself is truly impressive. Can you give some details about its meaning?

The first level is the process of discovering yourself. The characters begin to reflect on themselves. This is a good start.

“River” and “Ala Changso” highlights your knowledge about the way kids think. How did you manage to present this aspect so accurately?

I don't know. I am the father of two children. I like children very much. I used to be an elementary school teacher. Maybe it has something to do with this.

In “Ala Changso”, about halfway into the film, you change the person of focus, the protagonist. Why?

This is an attempt to present a different kind of script. “Ala Changso” is a road movie. If the heroine does not die, the following drama could not be sustained. I have been thinking about this part for a long time. I regard husband and wife as a whole, so I made this bold attempt.

“Ala Changso” is performed in a rather rare dialect. Can you give us some more details?

The film was shot in the Gyalrong Tibetan area of Sichuan. In addition, in the film, one can hear accents from the Ü (Central) Tibetan area, the Amdo Tibetan area, and the Kham Tibetan area. This is the first time the dialect from Gyalrong has been displayed, so I think it was good to show it on film.

The pilgrimage Drolma undertakes in the movie seems quite intense. Can you give us some more details about this custom?

I think it may not be so strong, because this is a road movie. The characters must have a strong motive. Pilgrimage is purely a behavior of faith. For example, if an old man dies, Tibetans will go to a pilgrimage. The purpose of the pilgrimage in each district is different, but Lhasa is always the destination of the pilgrimage

Regret seems to be another one of the main motifs of the film. Can you elaborate?

This is an aspect of the film that was based on my creative instinct when I was adapting the script written by Tashi Dawa. The initial theme of pilgrimage and repentance did not suit my purpose, I actually do not like the theme of the pilgrimage, because the pilgrimage becomes the only point of focus eventually. The original script revolved around an old man and a donkey, who go on a pilgrimage. Later, when the donkey grew old, there was no way to return from Tibet. I adapted this to what eventually became “Ala Changso”.