Seijun Suzuki the absurdist, the unreal-realist, the aesthete, sadly, has passed away at 93. He was one of the finest maverick craftsmen of popular Japanese cinema, who also created paradoxical, mind bending films. He brought a WWII veteran's eye, similar to his American alter-ego Sam Fuller, with a no-nonsense approach to dialogue, but tweaking that directness with his ‘entertainment over logic' idea.

Over the years Suzuki directed many exciting B-Movies for Nikkatsu Studios, all superbly crafted with consummate style, but many rose above their programme picture origins. In ‘The West' he is considered a cult filmmaker, but his job was to make popular genre B-movies for the Japanese public in the late 50s early 60s. His importance is his influence on Asian Cinema, rather on the usual suspects, Tarantino and Jarmusch in Hollywood. His influence on Takashi Kitano, Takashi Miike and some of Sion Sono's pictures are evident, and that is where his importance lies, back with Japanese genre cinema.

“Fighting Elegy” is Suzuki's great satire, a teenage brawling film, about repressed sexuality, expressed through violence. He uses wit about the rise of militarism/fascism in pre-war Japan. He tackles these disturbing themes in a satirical style, making the film more palatable to a mass audience. He reveals the sadistic ridiculousness of the situation in pre-war Japan, through the humour of teenage frustration with the opposite sex, offsetting it with fighting! The use of unsubtle jokes and gangs brawling for the sake of fighting, composes one of the more unusual ‘rise of fascism' B-movies, as he lets the action speak words.

As a director who abhorred realism, he would use realism, like a weapon, when it mattered. With a nation facing up to its wartime conduct, “Story Of A Prostitute” brings this honesty to full effect, exploring the absurd, brutal and nihilistic codes that infused the way of life in militarist Japan. This huge theme is dissected in an exciting war picture about a military comfort girl prostitute! Making frank films in the mid 60-s about army brothels in Manchuri, would have been something quite unique in Western cinema. Seijun Suzuki looked at it straight in the eye, and created a memorable B-picture. Not that this entire picture is in the realist style, there is a brief idyll for the lovers in a monastery, and many of the actual scenes of war have a hallucinogenic feel, which Coppola established in “Apocalypse Now” later. The French WWI poet Apollinaire wrote poetry about the bizarre surreal nature of carnage, all beautiful lights and exploding bodies. This is a war film though, Suzuki strips back the romanticism and ends it with sound and fury, signifying nothing! Driven by a deranged and sadistic code of conduct, no one can escape this insanity! He didn't focus on the politics but on the human behaviour these harsh codes created, ironically making them political. The high energy melodrama does all the talking.

Suzuki captured post-war Japan, as a scramble for survival, where a demoralised population try to figure a new code to live by, usually with Hobbesian results. Mini-militias of prostitutes create their own code to survive in “Gates Of Flesh”, by selling themselves in an organised gang fashion, protecting their turf, of bombed out Tokyo, viciously. This was no time for romanticism, frivolity or even love; this is a brutal game of survival. Any weakness must be dealt with, harshly. This lurid exploitation film has much merit. Seijun Suzuki pleased the studio, with masses of nudity and girl violence. Exploitative it is, but this is a female dominated picture, displaying the tough choices many young Japanese widows had to make after the war. He describes his own early period of film making, as an assistant director at Shochiku Company, as a melancholic drunk. Mr Suzuki himself struggled with the national ennui after the war.

Suzuki genre films are filled with Yakuza gangsters, hitmen, prostitutes and various outsiders clambering for survival. Many of the films have sensational titles, that are becoming available in The West; “The Naked Woman And The Gun”, “Detective Bureau 23: Go to Hell”, “Bastards!”, “Stories of Bastards: Born Under a Bad Star”, “Tattooed Life”, “Take Aim At The Police Van”, “Go To Hell Hoodlums!”

The 1963 gangster film “Youth Of The Beast” is when Suzuki felt he had finally found his feet, in a cinematic style he appreciated. Ultra-modern urban interiors and exteriors in the New-Wave style! Wild colours! Gangsters that have a primal, almost mythic intensity, that all need to die!

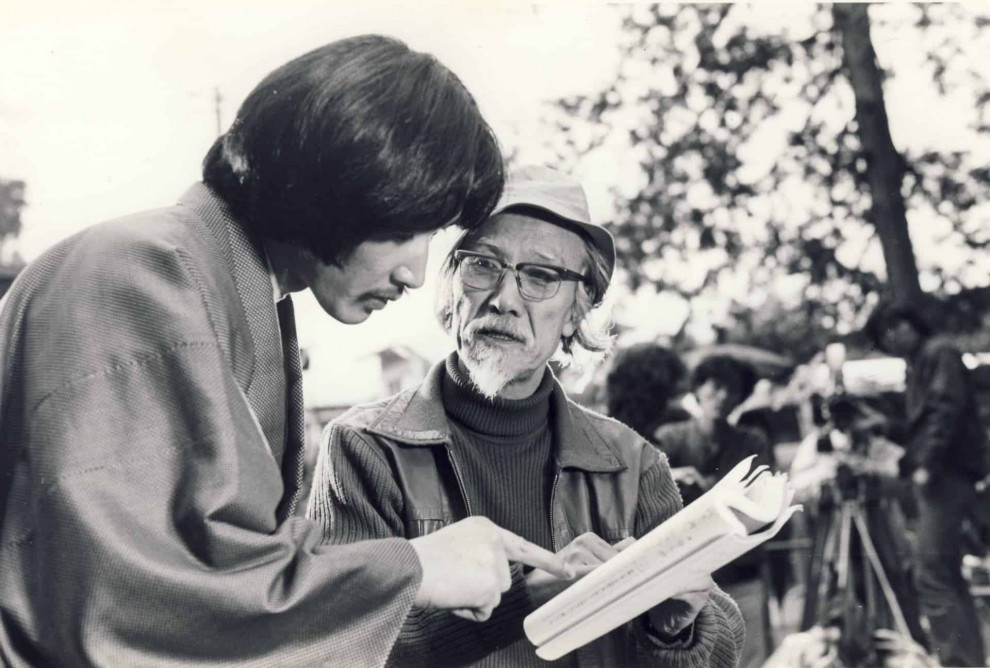

Seijun Suzuki worked within the confines of studio system at Nikkatsu, but he still pushed the boundaries with attention to detail, taking genre scripts and hammering out tough dialogue, moulding it into entertainment. Working with the finest cinematographers, art designers, and getting the best out of his actors, he tried to make these programme pictures, spectacles in their own right. Two people feature largely in Suzuki's studio career. Takeo Kimura, his production designer is a major influence on Suzuki's filmmaking. Kimura helped Suzuki achieve his eccentric visions, through the juxtaposition of modernity and absurdity, through his art design. The other, is the actor who featured in many of the Nikkatsu action pictures, Jō Shishido. Shishido and Suzuki worked together on many films, usually through Nikkatsu saying Shishido is ‘The Star' of whatever Suzuki was working on at the time. Their unlikely collaboration was a fruitful one, with the chipmunk cheeked actor giving fine performances throughout Suzuki's studio work. Though Suzuki considered himself a ‘company' man, giving the studio what it wanted, his trickster wit and dead pan cinematic black humour couldn't but help get him into trouble. Nikkatsu fired him, so he sued them in return and won! Sadly this led Suzuki to being blacklisted for a decade.

I would say that Suzuki had too much of a collaborating spirit, to be an auteur. Being a studio-system director meant such an approach would have been extremely difficult. To my sensibility he was a renaissance director of ideas, where the auteur style could be too much of a limitation; he was a true maverick of ‘popular' cinema. As with any great filmmaker, Suzuki had his own distinct absurdities and visual flair that mark out his oeuvre. He is like an experimental Raoul Walsh, with his eye for pace, great action, tough as nails dialogue, all blended with great performances from his actors, rounded up with energy and wit. Like Walsh, he could blend the current intellectual ideas into his popular cinema, sometimes subtly, sometimes overtly. As time went by, he combined Walsh style action with Bunuel surrealism and the French New Wave urban dislocation. His later action pictures transformed into mind bending experiences of style, filled with experimental cinematic jokes, but with an eye for extreme detail. It is in the specifics where things get even more absurd. A scene that could last 10 seconds in his nihilistic monster, “Branded To Kill”, is brimming with visual ideas and gags.

The pop-art palate of “Tokyo Drifter”, his Homeric gangster film is stuffed full of memorable shots, super stylised internal scenes with amazing art direction, and delirious external shots, on location. The scene in the snow, on the railway track, has a particular vivid colour palate and hyper-reality, this a wild film. The vibrant groovy suits these mod gangsters wear add to the dislocation. The pop-art finale, in the delicious neo classical nightclub, is pure eye candy.

Once Suzuki had overcome his blacklist he created the Taishō Roman Trilogy of Zigeunerweisen, Kageroza and Yumeji. These entertainments are perhaps more in the auteur style. Suzuki was away from the studio system, and he made longer, more contemplative period dramas, with a wider use of external location. His distinct use of art design, strange camera angles and a vivid colour palate are still all present in all these grand films, but in a more serene style. The frames are filled with colour, and there is much contemplation on art, music, plays and poetry. These films may be meditative, but Suzuki's motifs of randomness, doppelgangers, ‘ghostly going's on' and his usual random absurdist asides are still present, as Suzuki's inherent wit couldn't be repressed. Playfulness continues with these meditations on philandering aesthetes.

Suzuki himself saw film-making simply as a means to end, making a living. He found the process itself quite arduous, akin to a middle management position in a big corporation, especially in his programme picture days for Nikkatsu.. He may have had a simple objective when it came to making films, making money, but he admits he couldn't help himself trying to make the films more entertaining, throwing in wild visual ideas into cauldron. That doesn't mean purely messing round with narrative, like in “Branded To Kill”; a story can be quite straight forward, as in “Story Of A Prostitute”, but it is how the narrative is framed with experiments in space and time, peculiar camera angles, brilliant cinematography with heightened hallucinogenic delirium, immaculate set/art design that could take the narrative to new and interesting vistas.

When he was assistant director at the Shochiku Company, at the start of his career, he learned the process of concise filmmaking, to strict budgets. Get your plan, film it, and edit it, no superfluous scenes that are not going to be used. He kept to this tight style through his Nikkatsu era.

Suzuki's final flurry of filmmaking returned to his cinema of pure entertainment with “Pistol Opera”, in 2001. This is a remake/sequel to “Branded To Kill”, and he committed to it, in absurd style! His final film is the wildly inventive musical “Princess Raccoon”, crammed with genre busting ideas. After making this film in 2005, he knew that he was no longer physically capable of making another film, so he bowed out in surreal style, with this entertaining musical. He finished as he started, in song. His debut feature under his real name Seitarō Suzuki, was “Victory Is Mine” in 1956. This is a pop song film, used as vehicle for current popular hits of the time. He started in song, and finished with a humorous musical!